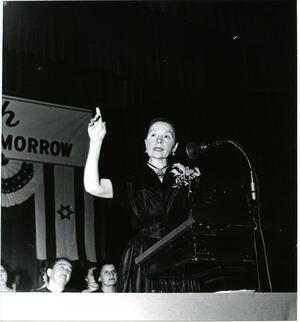

Rose Luria Halprin

Rose Luria Halprin helped lead Zionist organizations through the tumultuous period of Israeli independence and helped shape international opinions of Zionism. Halprin served as national president of Hadassah from 1932 to 1934 before moving to Jerusalem, where she helped build the Hadassah Medical Organization’s new hospital. After returning to the United States in 1939, she joined the Zionist General Council, became a founding member of the secretariat of the American Jewish Conference in 1943, and was elected an executive of the Jewish Agency in 1946. From 1947 to 1952 she served a second term as president of Hadassah. As a member of the Jewish Agency Executive, Halprin continued to fundraise and speak on behalf of Israel until her retirement in 1968.

Background

Rose Luria Halprin was one of the foremost American Zionist leaders of the twentieth century, serving twice as the national president of Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, and holding key posts within the Jewish Agency at critical periods in the history of the Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv and the subsequent State of Israel.

Born on April 11, 1896, in New York, Rose Luria Halprin was the daughter of Pesach (Philip) Luria, a dealer in silverware, and Rebecca (Isaacson) Luria. Her parents were ardent Zionists and gave her a Hebrew education. Even as a young girl, she was active in Zionist causes, serving as the leader of the Stars of Zion, a youth division of the Austro-Hungarian Zionist Society, to which her parents belonged. When the society nearly lost its meeting rooms on the Lower East Side because of a lack of funds, Halprin and two friends staged a benefit concert that raised the money necessary to pay the rent. In her later Zionist activities, she would often be called upon to muster vital resources in times of crisis and need.

She completed a course of study at the Teachers Training School of the Jewish Theological Seminary between 1912 and 1913, attended Hunter College briefly in 1914, and later took classes at Columbia University from 1929 to 1931. In 1914, she married Samuel W. Halprin, a businessman, and the couple and their two children made their home in Brooklyn.

Time in Palestine

From 1932 to 1934, Halprin served as national president of Hadassah. At the end of her term, she moved to Jerusalem with her family while serving as a liaison to the Hadassah Medical Organization during the construction of its new hospital complex on Mount Scopus. A member of the building committee, she was present at the hospital’s opening in 1939. Under the leadership of chair Judah L. Magnes, the building committee engaged German Jewish architect Erich Mendelsohn, who built a structure acclaimed for its beauty as well as its suitability for the Middle Eastern setting.

Halprin’s Jerusalem years made a deep impression on her. She perfected her Hebrew and came to know the people of the Yishuv on a more intimate level. She often spoke to friends of the long walks she took with her children through the Old City of Jerusalem and of the view of the Mount of Olives from her door. During her career, she would return more than sixty times to Palestine and, later, Israel.

Her time in Palestine also coincided with a wave of anti-Jewish rioting by Arabs in Hebron and other areas. She helped provide relief for Jewish settlers who came to Jerusalem from outlying areas to escape the violence. It was also a period of increased emigration from Germany, where the Nazi regime was beginning to implement anti-Jewish policies. Halprin became acquainted with Henrietta Szold, Hadassah’s founder, and assisted her in her work on behalf of Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah. She traveled to Berlin in 1935 and 1938 on Youth Aliyah missions.

Career in American Zionism

Halprin returned to the United States in 1938 on a speaking tour, reporting to Americans on the conditions of Jewish life in Palestine. Despite the seriousness of tensions between Jews and Arabs, she argued that cooperation between the groups was vital and would help to rid Palestine of its economic problems. Halprin blamed the British mandatory government for the Arab riots, citing its failure to live up to promises made in the Balfour Declaration, and for alternately favoring Arab and Jewish interests according to political expediency.

Halprin returned permanently to the United States in 1939, but her experience in Palestine led to her increasing involvement in international Zionist affairs. From 1939 to 1946, and occasionally thereafter, she was a member of the Zionist General Council, the supreme advisory and supervising institution of the Zionist movement. In 1942, she became treasurer of the American Zionist Emergency Council and served as its vice-chair from 1945 to 1947. She was one of the original members of the secretariat of the American Jewish Conference, which was founded in 1943 to coordinate American efforts on behalf of Palestine. In 1946, she was elected to the executive of the Jewish Agency, a post she held for over twenty years.

Halprin faced her most dramatic leadership challenges, however, during her second term as Hadassah president between 1947 and 1952. A tremendous blow came to Hadassah’s efforts in Palestine when more than seventy-five doctors, nurses, and students were killed in an ambush as their convoy passed through the Arab neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah on its way to Mount Scopus. The attack underscored the hospital’s vulnerable position surrounded by Arab-held territory, and the complex was evacuated. Under Halprin’s leadership, five temporary facilities were set up in Jerusalem to deal with the urgent medical needs resulting from the War of Independence. Meanwhile, the Medical Organization continued to grow during her presidency, with the establishment of the Hebrew University–Hadassah Medical School in 1949, and the breaking of ground for a new permanent Hadassah Hospital at Ein Karem in 1952.

In addition to her involvement with Hadassah, Halprin played a pivotal role during the struggle for Israel’s independence as a member of the American Section of the Jewish Agency, which was charged with arguing for the establishment of the State of Israel before the United Nations. She participated in negotiations that led to the acceptance of the Partition Plan in 1947. Later, when fear of bloodshed caused the United States to recommend a delay of statehood and a temporary “trusteeship” over Palestine, Halprin was one of four members of the Zionist General Council who brought word from Jerusalem that Jewish officials were determined to bring the new state into existence as planned. After independence, she continued to serve on the Jewish Agency executive, and was asked by Finance Minister Eliezer Kaplan to head an international effort to raise the funds necessary for Israel to absorb the streams of new immigrants entering the country. From 1956 to 1963, and intermittently until 1968, she headed the American Section, first as acting chair and, after 1960, as chair.

In her work for the Jewish Agency and its parent body, the Zionist General Council, Halprin always stressed the mutual reliance of Israel and American Jewry. Much in line with the founding principles of Hadassah, she saw the State of Israel as embodying American ideals of justice and equality, while serving as a source of spiritual and cultural renewal for American Jews. Thus Halprin insisted on an involvement for American Jews in Israel that went beyond philanthropy, and demanded recognition for such a role from the Israelis. As she admonished the Zionist General Council in 1953, “As long as you look on America only as a potential something or other for Israel, you will not help us, and if you do not help us, you will lose Jewish life in its strength and its numbers.”

Known for her wit and public-speaking skills, she was at home in the often fierce world of Zionist politics. “She never gave up the right to be heard,” recalled Bernice Tannenbaum, one of Halprin’s successors in the Hadassah presidency, “and such was her power of persuasion that she usually carried you along her road whether you willed it or not.” In her later years, an incident that drew strong comment from Halprin was the United Nations 1975 resolution equating Zionism with racism. Although a seasoned international negotiator, she instructed Hadassah members that the most appropriate response was not to protest through diplomatic channels, but to articulate their own definition of Zionism more forcefully through the work they did. Her strong personal qualities and organizational abilities made her perhaps the most revered Hadassah leader since Henrietta Szold.

Rose Luria Halprin died on January 8, 1978.

Cohen, Naomi W. American Jews and the Zionist Idea (1975).

Freund-Rosenthal, Miriam, ed. A Tapestry of Hadassah Memories (1994).

Haber, Julius. The Odyssey of an American Zionist (1956); Hadassah Magazine (February 1978): 9

Halprin, Rose. Oral history interview with Judith Epstein, and Papers. Hadassah Archives, NYC.

Obituary. NYTimes, January 9, 1978, IV 7:3.