Greek Resistance During World War II

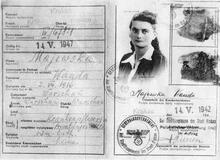

Courtesy of the Jewish Museum of Greece, Athens.

Sephardi and Romaniote women who were active in resistance movements in Greece and in Auschwitz-Birkenau have rarely been mentioned in historical literature on World War II. However, a number of young Jewish women joined the Greek resistance during the deportations in the spring of 1943. Many of them went on to serve the resistance in ways that often belie their somewhat genteel upbringings and high levels of education. They served as nurses, runners, contacts, and smugglers of weapons and propaganda, as well as being part of the fighting units of ELAS. A few Greek women were also involved in passing dynamite for use in the Sonderkommando Uprising in Birkenau.

The Axis Invasion of Greece

On October 28, 1940, Italy invaded Greece but was rapidly chased back into Albania, where the Greeks held the Italians under siege for the next five months. In April 1941, responding to Mussolini’s call for help, the Germans invaded and overran Yugoslavia and Greece. By the end of May the bloody fighting in Crete ended mainland Greek independence; the king and his government relocated to Cairo, and sporadic resistance continued in the mountains. In the subsequent partition, Bulgaria realized its irredentist claims to Macedonia and Thrace. Germany took Salonika and environs, the stretch along the Turkish border to separate the Bulgarians and the Turks, and most of Crete. The remainder of mainland Greece and its islands, several, such as Rhodes and Kos, already occupied before the war, were allocated to Italy.

Already in the fall of 1941 the two main wings of the Greek resistance were forming: EAM (Ethniko Apeleutherotiko Metopo—the National Liberation Front) and EDES (Ethnikos Demokratikos Metopon—the National Republican Liberation Front). EAM was a loose confederation of pre-war parties that had been silenced during the dictatorship of John Metaxas (August 1936–January 1941); it was secretly dominated by the remnants of the Greek Communist Party that had been neutralized and all but destroyed under Metaxas.

The deportation of the Jews from Bulgaria in March 1943 must be seen in light of Bulgaria’s alliance with the Reich and its acquiescence to German demands. Even so, the Nazi negotiations for 20,000 Jewish workers and their families from Bulgaria were honored by the deportation to Treblinka of some 12,000 Jews from former Yugoslavian Macedonia and from Bulgarian-occupied Greek Macedonia and Thrace. The remaining 8,000, who should have come from pre-war Bulgaria, were never supplied, and upon this latter record rests the Bulgarian claim to be rescuers of Jews. The complicated story of the pre-war ethnic tensions in Greek Macedonia that were exacerbated into civil war by the three occupying armies and the internecine conflict among the resistance forces need not concern us here. They are still being unraveled.

Jewish Women in the Greek Resistance

In 1943–1944 an unknown number of teenage Jewish girls joined the general exodus of the Greek Resistance to the safety of the mountains. Many of them left their extended families, who were soon herded by Germans and Bulgarians to the gas chambers of Auschwitz and Treblinka.

Jewish girls who escaped to the mountains during the deportations of the spring of 1943 came from a largely patriarchal society that had protected its women from too much contact with the harsh realities of Balkan public life. Nevertheless, the girls had received excellent educations, whether in Spanish, French, Italian, German, or the national Greek culture. Many were polyglot with a keen interest in the outside world into which they had increasingly entered during the inter-war period. These young women served resistance movements in ways that often belied their somewhat genteel urban upbringing and high level of education.

In the cities of the Italian zone where Jews were not persecuted, women acted as runners, contacts, and smugglers of weapons and propaganda. Because of their language skills, others were able to communicate with the occupiers and so assist in the rescue of endangered resistance activists. Some joined the resistance women who acted as escorts for Axis officers and so contributed to the flow of information that flooded British intelligence centers. British Special Operations Executive (SOE) files contain the names of several women agents on their payroll.

Nursing

Matilda Bourla (1913-1993) became interested in nursing after seeing a film biography of Florence Nightingale. Despite family objections to this interest, she left Salonika to visit her uncle in Athens, who helped her enter training. Many Jewish nurses served with the Greek Red Cross during the war against Italy in 1940–1941. A number of them later served with the resistance, whether EAM in the cities or its military wing ELAS in the mountains.

Bourla worked in the Elpis Hospital in Athens until she fell in danger of arrest by the Gestapo after the Germans took over the Italian zone in September 1943. She was rescued by none other than the king’s personal physician and was helped in escaping to the mountains above Thebes, where she assisted at a resistance hospital. When German patrols threatened to overrun the site, the nurses moved their patients higher up the mountain, each one carrying a wounded man on her back for several hours. For decades, Bourla suffered from back pains and rheumatism from her mountain adventures, the medals for valor and service she received from France and Greece providing little compensation.

Another nurse, Fanny (Flora) Florentin (b. 1920 in Salonika), served with the Greek Red Cross in Albania. In March 1943, she and her husband Leon escaped to the mountains of Paiko where she served as a nurse to a Jewish doctor (Dr. Yanni, later killed during the civil war) and trained young village girls to be nurses’ aides. During a horrendous withdrawal from a German search-and-destroy mission in the area of Gravena (inside Yugoslavia) in fall 1944, Fanny remained with her now-abandoned wounded andartes (resistance fighters) and was captured along with Salomon Matalon. Before he killed himself, their communist leader gave her a knife, presumably to do the same. Fanny was taken to jail in Ioannina, where she defiantly told the SS she was a Greek citizen and Jewish; they sent her by train to Trikkala and eventually to Pavlos Melos prison in Salonika. When news of her arrival at the prison reached her sister Maidi through the wife of a Greek doctor, Maidi contacted a friend of Flora’s, a Belgian named Mrs. Riades, in the International Red Cross. Flora was then abducted from Pavlos Melos by resistance members who bribed the guards to let them in after word got out that she was to be executed. Her story illustrates both the Jewish contributions to the mountain story and the opportunity for survival in the city where influential friends had the potential to save their Jewish colleagues.

Into the Mountains

Daisy Carasso (b. 1926 in Salonika) was educated in a Greek public school and completed only a few years of high school due to the war. Of all her male relatives, only her father Alberto and younger brother Marko were not drafted during the war. In April 1941, when the Germans entered Salonika and began to confiscate Jewish businesses, including the Molho bookstore, the largest in Macedonia, her father lost his job as its manager. During the mass arrests of the summer, he was taken hostage; after eighteen months in various jails he was shot on December 30, 1942, in reprisal for the destruction of a bridge by the resistance. Marko received his father’s watch from students who worked in the prison, who told him his last wish was that Marko protect the family and that he join the resistance to fight against the Germans. Many of Daisy’s father’s and brother’s friends eventually joined the andartiko (fighting resistance). Marko went into hiding with Christian friends during the continued roundups for forced labor. Daisy acted as liaison with her brother and other young men he had recruited for the resistance. When she tried to arrange for the latter to escape to the mountains, however, she was chased away by the family matriarchs. A number of her friends who were active in Zionist youth movements also joined the resistance.

In early April 1943 Daisy Carasso left for the mountains with her mother and her young sister, through the arrangement of a Jew who was friendly with a black marketeer who was also the local recruiter for the Communist Party and the andartiko from the village of Dafni near Nigrita. After a number of adventures, including passing her mother off as a long-term resident of France to account for her peculiar Greek accent, they reached the village of Todorakia, where the local teacher hosted them through Easter. When an informer appeared, the local policeman warned them to escape; they left for Kilkis, where the doorman of their building in Salonika lived. Lacking documents, they had to return to the villages. Eventually they reached Nigrita where Daisy joined the resistance. Such experiences illustrate the reasons why more Jews, especially among the poor, did not escape to the mountains.

Nigrita, with its population of about 9,000, was the center for ELAS Regiment 19, which had broad support from the intellectuals and professionals of Nigrita and especially the teachers. Carasso joined EPON (the Resistance Youth Movement), where she helped to prepare food and clothes and assisted the families of andartes left in the 22 villages surrounding Serres and Nigrita. She also helped recruit young men, did guard duty, carried ammunition, and distributed leaflets and propaganda in Nigrita. There were demonstrations on national holidays and once, when the Germans and Bulgarians shot up one such demonstration, she led the young girls in a circle dance around the monument to the unknown soldier, singing the death song of the Suliote women from the 1821 War of Independence. After the war she returned to Salonika and married Yizhak Moshe, who was known as Kapitan Kitsos for his wartime leadership, and in 1949 immigrated to Israel.

Participation in ELAS Fighting Units

Many women were part of the fighting units of ELAS which, inter alia, preached a liberation of women from the bonds of patriarchalism. The Greek villagers reluctantly supported this revolutionary message, which was an integral part of the new society that EAM/ELAS had introduced into the mountains it controlled. After the war the village males quickly rejected this particular heresy. The Greek Right and the British condemnation of the Left (EAM) resistance as communist made it easier for the villagers to regain control over their women after the war. However, tens of thousands of Greek women refused to give up their belief in the liberation of women and many spent a decade, even two, in postwar prisons for refusing to recant their participation in the resistance and its revolution.

World War II opened a new chapter in warfare with the appearance of women fighters, particularly in the Communist-dominated partisan movements. While there were some hard-core Communists among them, many of the women were socialist-leaning educated girls who recruited village girls or were themselves refugees from Axis persecution. Morality was more than strict. The army protected their virtue by threatening violators with death. However, it did allow andartes to marry each other and provided a village priest for that purpose.

Several Jewish women are particularly interesting, especially since Jews do not appear in the general literature about the resistance or in recent studies about the women of the andartiko. Dora Bourla (b. 1926 in Naousa) fought in the mountains of Macedonia and was known as “Tarzan” to her fellow fighters. Her sister Yolanda (b. 1916 in Cairo), trained as a nurse, also served in the mountains. Another Jewish girl was part of a female fighting unit of 30 women. At the end of the war in Greece a Jewish member of parliament, who had learned that the communist leadership had decided to ship this unit to Korea as a sign of solidarity, rescued her from the group. Dora was fortunate; all the women were killed in Korea.

Sara Yehoshua (b. 1926 in Chalkis), known as Sarika, at the age of fourteen became a nurse in her native Chalkida, the capital city of the island of Euboea, where wounded soldiers and amputees from the Albanian front were sent. In 1943 she and her mother escaped the German roundups and went by mule to the mountain villages, where she taught for a while until the Germans burned the village for harboring Jewish refugees. Sporting bandoliers she went higher up the mountain to work at the Resistance Command Post in Steni. When it was decided to form a women’s unit she was a natural candidate, and so, at the age of seventeen, she became a kapitanissa and chose a squad of twelve girls from those she had recruited.

Sarika and her squad functioned as a diversionary unit. Armed with Molotov cocktails, they attacked outlying sites to draw the Germans away from the main target. When the Germans arrived all they found was a group of girls playing. They also aided in the capture of collaborators. Sarika herself was granted permission to hunt down and kill an informer who had sadistically tortured and murdered a young Jewish teacher, Menti (Mendy) Moshowitz of Salonika, who was hiding in the same village as Sarika, who was herself the intended target.

Sarika came from a family of heroes. A statue to her uncle Mordecai Frizis stands in her native Chalkida; he was the highest-ranking Greek officer to fall leading his men in the successful counterattack that turned back the flank of the Italian invaders in November 1940. In 1991 when Saddam Hussein responded to the American attack on Iraq by sending SCUDs to bomb Israel, her house was the first to be destroyed by a direct hit. Fortunately she was with her son, a decorated but invalid veteran of the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

In Birkenau

The story is not limited to Greece proper. Some Jewish women in Crete assisted the resistance there. Moreover, a relatively unknown story is the Greek experience in the concentration camps. The main story is the period leading up to the Sonderkommando Uprising in Birkenau. We now know about 30 young women, mainly Polish speaking girls, successfully smuggled gunpowder to the Sonderkommando through a complicated network. Recently we have learned that a few Greek girls, organized by a well-placed Salonika youth Jacob Maestro, were involved in passing dynamite obtained from the road-building kommando through a network to Joseph Baruch, one of the leaders of the revolt, himself a Greek army officer. Their names are Matilda Hagoel, Allegra Uziel, and Arlette Yeruziel, not mentioned among the 30 or so Polish women who smuggled gunpowder from their arms factory.

The variegated story of the women in the Greek Resistance during World War II has much to teach and more to inspire, as recent scholarship indicates. A great deal still needs to be done, however, not only on the theoretical level but also—primarily—on the practical level of uncovering their deeds and the ideas that motivated them to rebel against an age-old system and embrace a revolutionary ideology aimed at liberating not only their country but also, especially, themselves.