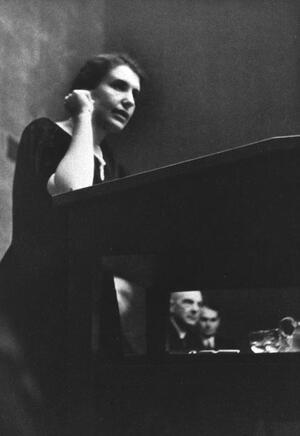

Anna Freud

Anna Freud shaped the fields of both child and developmental psychology. Her father, Sigmund Freud, began psychoanalyzing her in 1918, sparking her own interest in psychology. She became a member of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society in 1922 and the following year began analyzing children. From 1927 to 1934 she served as general secretary to the International Psychoanalytical Association. In 1935 she became director of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Training Institute. In 1938 she and her family fled Austria for England, where she offered foster care for children during World War II, created the Hampstead Child Therapy Courses in 1947, and established the Hampstead Children’s Clinic in 1952. In 1965 she published Normality and Pathology in Childhood, shaped by her work with children of all social brackets in peace and wartime.

Family and Education

Born on December 3, 1895, in Vienna to a Jewish family, Anna was the youngest of Sigmund and Martha (née Bernays) Freud’s six children. She was a lively child, with a reputation for mischief. She grew up somewhat in the shadow of her sister Sophie, who was two and a half years her senior, but was very close to her father, the founder of psychoanalysis.

When Anna completed her education at the Cottage Lyceum in Vienna in 1912, she had not yet decided upon a career. In 1914 she traveled alone to England to improve her English. She was there when war was declared and thus became an “enemy alien.” (Twenty-five years later, in 1939, this experience was to be repeated, but unlike other Jews at the time, she was not interned.) She returned to Vienna with the Austro-Hungarian ambassador and his entourage, via Gibraltar and Genoa. She began teaching at her old school, the Cottage Lyceum, where she was held with regard and respect.

Early Involvement in Psychoanalysis

Already in 1910 Anna had begun reading her father’s work, but her serious involvement in psychoanalysis began in 1918, when her father began psychoanalyzing her (a somewhat unusual arrangement even at the time, yet it should be remembered that this was before any treatment orthodoxy had been fully established). In 1920, they both attended the International Psychoanalytical Congress at The Hague.

Anna and her father now had both work and friends in common, some of them culturally distinguished. One such friend was the writer and psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé, who was once the confidante of Nietzsche and Rilke and who was to become Anna Freud’s confidante in the 1920s. Through her the Freuds also met Rilke, whose poetry Anna Freud greatly admired. Her volume of his Buch der Bilder bears his dedication, commemorating their first meeting. Anna’s literary interests paved the way for her future career as a psychoanalyst, a profession that she began viewing as crucial in deciphering inner life. “The more I became interested in psychoanalysis,” she wrote, “the more I saw it as a road to the same kind of broad and deep understanding of human nature that writers possess.”

Child Analysis

In 1922 Anna Freud presented her paper “Beating Fantasies and Daydreams” to the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society and became a member of the Society. In 1923 she began her own psychoanalytical practice with children and two years later was teaching a seminar at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Training Institute on the technique of child analysis. Her work resulted in her first book, a series of lectures for teachers and parents entitled Introduction to the Technique of Child Analysis (1927), a seminal study of children that launched her career as one of the pioneers of child psychoanalysis.

In 1923 Sigmund Freud began suffering from cancer and became increasingly dependent on Anna's care and nursing. Later, when he needed treatment in Berlin, she was the one who accompanied him there. His illness was also the reason why a “Secret Committee” of supporters of his work was formed to protect psychoanalysis against criticism from within and from outside the emerging psychoanalytic movement. From 1927 to 1934 Anna Freud was General Secretary of the International Psychoanalytical Association. She continued her child analysis practice and ran seminars on the subject, organized conferences, and, at home, continued to help nurse her father. She also acted as his representative at such public occasions as the dedication of a plaque at his birthplace in Freiberg or his award of the Goethe-Prize in Frankfurt.

In 1935 Anna became director of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Training Institute, a fact that exemplifies the openness of the new discipline of psychoanalysis to women occupying professional positions. The following year she published her influential study of the “ways and means by which the ego wards off unpleasure and anxiety,” The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence. In examining ego functions, the book was a move away from the traditional bases of psychoanalytical thought; rather than drives, it became a founding work of ego psychology and established Anna’s reputation as a pioneering theoretician.

The economic and political situation in Austria deteriorated in the 1930s. Anna Freud and her lifelong friend, and possibly her partner, Dorothy Burlingham, were concerned by the situation of the poor and involved themselves in charitable initiatives. In 1937 she had the opportunity to combine charity with her own work when the American Edith Jackson funded a nursery school for the children of the poor in Vienna. Anna and Dorothy, who ran the school, were able to observe infant behavior and to experiment with feeding patterns. They allowed the children to choose their own food and respected their freedom to organize their own play. Though some of the children’s parents had been reduced to begging, Anna wrote “we were very struck by the fact that they brought the children to us, not because we fed and clothed them and kept them for the length of the day, but because ‘they learned so much,’ i.e. they learned to move freely, to eat independently, to speak, to express their preferences, etc. To our own surprise the parents valued this beyond everything.”

Flight to England

Unfortunately, within a few months, in March 1938, the nursery had to close. Austria was taken over by Nazi Germany and the Freuds had to flee the country as Jewish refugees, despite Sigmund Freud’s ill health. Ernest Jones and Princess Marie Bonaparte provided vital assistance in obtaining emigration papers, but it was Anna above all who had to deal with the Nazi bureaucracy and organize the practicalities of the family’s emigration to London. Anna quickly settled down to work in her new home. “England is indeed a civilized country,” she wrote, “and I am naturally grateful that we are here. There is no pressure of any kind and there is a great deal of space and freedom ahead.” She was among the lucky ones among Jewish refugees at the time.

In early September 1939 the Second World War broke out, and within a few weeks Sigmund Freud died in London. Anna Freud had already established a new practice and was lecturing on child psychology in English. Child analysis had remained relatively uncharted territory in the 1920s and 1930s. Two of Anna's mentors in child psychology, Siegfried Bernfeld and August Aichhorn, had both had practical experience of dealing with children in Vienna. Melanie Klein, who ended up in England, was evolving and pioneering too her own theory and technique of early development of child analysis. She differed from Anna Freud as to the timing of the development of object relations and internalized structures; she also put the oedipal stage much earlier and considered the death drive to be of fundamental importance in infancy. After Anna's arrival in London, the conflict between their respective approaches threatened to split the British Psycho-Analytical Society. This was resolved through a series of war-time “Controversial Discussions” that ended with the formation of parallel training courses for the two groups.

After the outbreak of war Anna set up the Hampstead War Nursery, which provided foster care for over eighty children. She aimed to help the children form attachments by providing continuity of relationships with the helpers and by encouraging mothers to visit as often as possible. Together with Dorothy Burlingham, she published studies of the children under stress in Young Children in War-Time and Infants Without Families.

There was a further opportunity after the war to observe even more parental deprivation. After a group of Jewish orphans from the Theresienstadt camp came into the care of Anna Freud’s colleagues at the Bulldogs Bank home, she wrote about the children's ability to find substitute affections among their peers, in an important article titled An Experiment in Group Upbringing.

Postwar Career

In 1947 Anna Freud and the analyst Kate Friedlaender established the Hampstead Child Therapy Courses, and a children’s clinic was added five years later. Now that she was training English and American child therapists, her influence in the field grew rapidly. “The Hampstead Clinic is sometimes spoken of as Anna Freud’s extended family, and that is how it often felt, with all the ambivalence such a statement implies,” one of her staff wrote. At the Clinic, Anna and her staff held highly acclaimed weekly case-study sessions, which provided practical and theoretical insights into their work. Their technique involved the use of developmental lines charting theoretical normal growth “from dependency to emotional self-reliance,” and diagnostic profiles that enabled the analyst to separate and identify the case-specific factors that deviated from, or conformed to, normal development. In her book Normality and Pathology in Childhood (1965), she summarized material from work at the Hampstead Clinic, as well as observations at the Well Baby Clinic, the Nursery School, the Nursery School for Blind Children, the Mother and Toddler Group, and the War Nurseries. In child analyses Anna felt that it was above all transference symptoms that offered the “royal road to the unconscious.”

From the 1950s until the end of her life Anna Freud traveled regularly to the United States to lecture, to teach and to visit friends. It was there too that she found perhaps the most eager audience to her theories. During the 1970s she was concerned with the problems of working with emotionally deprived and socially disadvantaged children, and she studied deviations and delays in development. At Yale Law School she taught seminars on crime and the family, leading to a transatlantic collaboration with Joseph Goldstein and Albert Solnit on children and the law, published as Beyond the Best Interests of the Child (1973).

Honors and Legacy

Anna Freud also began receiving a long series of honorary doctorates, starting in 1950 with Clark University (where her father had lectured in 1909) and ending with Harvard in 1980. In 1967 she received an OBE from Queen Elizabeth II; in 1972, a year after her first post-war return to her native city, Vienna University awarded her an honorary medical doctorate. The following year she was made honorary president of the International Psychoanalytical Association. Like her father, she regarded awards less in a personal light than as honors for psychoanalysis, though she accepted the praise with good grace and characteristic humor; the speeches about her achievements made her feel as if she were already dead, she commented.

The publication of her collected works was begun in 1968, the last of the eight volumes appearing in 1983, a year after her death. In a memorial issue of The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, collaborators at the Hampstead Clinic paid tribute to her as a passionate and inspirational teacher, and the Clinic was renamed the Anna Freud Centre. In 1986 her home for forty years was, as she had wished, transformed into the Freud Museum.

Anna Freud’s work continued her father's intellectual adventure. Her life was also a constant search for useful social applications of psychoanalysis, above all in treating, and learning from, children. “I don’t think I’d be a good subject for biography,” she once commented, “not enough ‘action’! You would say all there is to say in a few sentences: She spent her life with children!”

Selected Works by Anna Freud

With Dorothy Burlingham. Infants Without Families: The Case For and Against Residential Nurseries. New York: International Universities Press, 1944.

The Psycho-Analytical Treatment of Children. London: Imago Publishing Co. Ltd, 1946.

Psychoanalysis for Teachers and Parents: Introductory Lectures. New York: Emerson Books, 1947.

Das ich und die Abwehrmechanismen. München: Kindler Verlag, 1964.

Indications for Child Analysis and Other Papers, 1945–1956. New York: International Universities Press, 1968.

The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence. London: Hogarth Press, 1968.

Research at the Hampstead Child-Therapy Clinic and Other Papers, 1956–1965. New York: International Universities Press, 1969.

Problems of Psychoanalytic Training, Diagnosis, and the Technique of Therapy, 1966–1970. New York: International Universities Press, 1971.

Normality and Pathology in Childhood, Assessments of Development. London: Penguin Books, 1973.

Introduction to Psychoanalysis: Lectures for Child Analysts and Teachers, 1922–1935. New York: International Universities Press, 1974.

Kranke Kinder: Ein Psychoanalytischer Beitrag zu Ihrem Verstaendins. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 1976.

Psychoanalytic Psychology of Normal Development 1970–1980. New York: Hogarth Press, 1981.

Die Schriften Der Anna Freud. 10 volumes. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1987.

The Harvard Lectures. Ed. and annotated by Joseph Sandler. New York: Routledge, 1992.

With permission of the Freud Museum, London

Sandler, Joseph. The Technique of Child Psychoanalysis: Discussions with Anna Freud. Cambridge, Mass: 1980.

Heller, Peter S. A Child Analysis with Anna Freud. Madison, Conn: 1990.

Sayers, Janet. Mothering Psychoanalysis: Helene Deutsch, Karen Horney, Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. London: 1991.

Coles, Robert. Anna Freud Oder der Traum der Psychoanalyse. Frankfurt am Main: 1995.