Filmmakers, Independent European

The post-World War II generation of Jewish women filmmakers present memory, community, politics, and feminist perspectives, utilizing visual innovations and pioneering new subjects for exploration. The substantial success of many the women filmmakers in Europe attests to their ability to preserve or recreate what was lost as a community. The body of work created by women filmmakers in Europe is a testament to the efforts of Jews to re-calibrate community and family in the years following the traumas of World War II. These films preserved for future generations family histories, immigrant stories, and the memory of those who perished. With the emergence of a new generation artists, there are also new themes exploring intergenerational relations and acculturation of immigrants into new societies and in Israel.

The post-World War II generation of European Jewish women filmmakers are telling stories that preserve memory, document history and give voice to feminist yearnings. Their success as filmmakers comes in part because of the popularity of film in general and how effective cinema is as teaching device that helps the viewer imagine what has been lost. Central European films are reflective of the Jewish experience of loss, outsider-ness and memory. Others stories explore the courage of individual acts of resistance during World War II. Western European directors re-tell personal stories of friendship and betrayal in a context of Europe without its Jews. There is also a strong body of work from France of North African-born filmmakers reflecting upon the historic relationship between Arabs and Jews in that region.

European directors in general are supported by a complex network of funding bureaucracies that include government film funds, European television money and investors. The notion of “independent” in Europe is similar to that in the United States, where commercial Hollywood fare dominates and independent cinema is the "alternative.” Ironically, European artists are all independent in the face of competition with Hollywood films that control local cinemas. Many countries want to support their own national cinema and do so through taxes on cinema tickets and laws encouraging art works made in their native language. These funding sources constitute the lifeline for European women filmmakers who create compelling works. These films find audiences through the worldwide network of Jewish film festivals and through internet streaming platforms.

Eastern Europe: Poland, Hungary

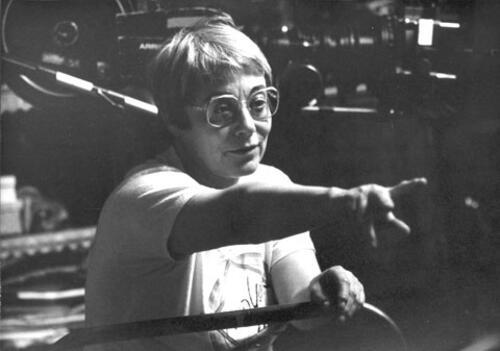

Agnieska Holland (b. 1948) brings a unique and authentic vision to her narratives and is clearly the most successful of the Jewish women directors in the post-war era. Born in Warsaw, she left Poland to study at the famed Prague film school together with classmates such as Milos Forman. She worked for many years as an assistant to Krystof Zanussi and Andre Wajda. Her solo career as a director was launched with Angry Harvest (1985), a complicated exploration of Jewish and non-Jewish and male/female power relationships, produced in Germany. Set during the war years, it presents Leon, a Polish Catholic farmer with mixed motives, who hides Rosa, an intellectual Jewish refugee. In an intense all-too-real relationship, they maneuver in various states of power and powerlessness. Angry Harvest received an Oscar nomination in West Germany.

In Europa, Europa (1990), Holland remained in the war era but moved to a story of triumph and survival. This film is based on the real-life experiences of Solomon Perel, who survived the Nazi death camps by swimming to Russia and joining the Communists, then eluded the Nazis again by literally becoming one of them. The film was reviewed in Le Monde as “heavy, cumbersome and demonstrative types, a kind of cinema that makes one queasy” and was initially poorly received by European audiences, especially in Germany. It was rescued from oblivion when it was discovered at the Toronto Film Festival in 1991 by Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics. Europa, Europa became one of the highest grossing ($7 million) foreign films of 1992. It was nominated for and won Best Foreign Film by the New York Film Critics and the National Board of Review and won a Golden Globe for the Best Foreign Film, but in a much-contested decision, the Germans declined to submit it to the Academy Awards for consideration as the Best Foreign Film.

Holland continued her career in television with directing projects for HBO, most notable Treme about post Katrina New Orleans. In March 2010, she returned to the large screen with In Darkness, a film based on In the Sewers of Lvov, Robert Marshall's heroic tale of surviving the Holocaust. It is a story of transformation in the face of extreme adversity and the fight for survival. The hero Soha, a Gentile who decides to save Jewish lives, reveals the evolution of an anti-Semite into a redemptive guardian angel. Holland has described her approach to the film as straightforward and realistic: “They lived in the dark, stink, wet and isolation for over a year. We knew we had to express it, to explore this underground world in a very special, realistic, human and intimate way. We wanted the audience to have the sensory feeling of being there.” (Culture.pl, January 2013). Derived from a true story, the film finds the right tone of suspense by keeping the audience in the sewers, with all their claustrophobia, experiencing what it might be like to live in constant fear without light or fresh air. In Darkness was nominated for an Academy Award, Best Foreign Film, in 2011.

The Jewish women directors of the post-war generation take on their own identity quest with films that look at their national histories. The works of Hungarian filmmaker Judith Elek (b. 1937)—Memories of a River (1989), Awakenings (1994), A Free Man: The Life of Erno Fisch (1996)—directly address Christian antisemitism in Hungary. Thus, when Elek chose to recreate a traumatic period in Memories of a River (in which fourteen Jewish small businessmen and peddlers, together with seven river raftsmen of mixed nationalities, are unjustly charged with conspiracy and the ritual murder of a Christian servant girl), the film set off a national debate. Elek’s film stirred up latent bigotry and added fuel to the contemporary controversies about Jews. Elek also saw the film as an investigation into the antisemitic world into which she was born. She leaves the audience with the memory that when there was tolerance, people in Hungary could live together.

Hungarian filmmaker Erika Szanto (b. 1941) has devoted a good portion of her career as a writer and director to telling the true stories and tragic historical events that befell the Jews of Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. Her feature film Elysium (1986) tells the painful story of the secret Nazi experiments on children with an innocence that belies the horror. The children are never fully aware of what is happening to them, while the medical teams show a detachment that exemplifies the concept of the banality of evil. Szanto chose a real event, the 1938 Conference in Evian, for her poignant film, Mission to Evian (1987). In 2001 she completed a documentary, For the Good of the Nation, about the forced labor of Hungarian Jews during World War II—a group that included her father.

Germany

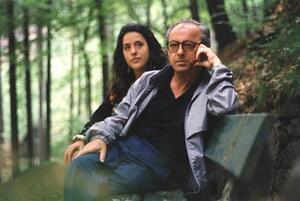

Jeanine Meerapfel’s (b. 1943) work directly reflects her family’s experience of displacement, immigration and acculturation. Jeanine was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, when her family was forced to flee Germany in the early 1930s. Moving to Germany in 1964 to attend film school, she later addressed the irony of her choices in her search for her Jewish identity in Germany in the documentary In the Country of My Parents (1981).

Meerapfel’s first feature film, Malou (1980), based on the story of her mother, tells the story of young Hannah, obsessed by the memory of her own mother. This semi-autobiographical film follows the rise and fall of a woman who was betrayed by men and history as she moved from France to Germany and then to the slums of Buenos Aires. Meerapfel’s work also explores from a feminist perspective the tragedy of women who lack the choices or options to control their own destinies. Malau was honored with a Retrospective at the 2019 Berlin Film Festival.

Similar issues emerge in the Argentinean/German production of Meerapfel’s La Amiga (1988). Meerapfel recounts the lifelong friendship between Raquel and Maria, each making different life choices. Raquel, who is Jewish, pursues a career as an actress; Maria marries and has a family. Both lives are turned into chaos when Maria’s eldest son “disappears,” a victim of General Alfonsin’s “dirty war” against the people of Argentina. This moving story reveals the possibility of personal transformation through political commitment. La Amiga presents the modes of action available to women in the face of overwhelming political oppression.

Meerapfel completed her trilogy of the lives of Jewish women with Anna’s Summer (2001). Set on a Greek Island, the film is about a middle-aged recently widowed woman who returns to her grandmother’s house on the Mediterranean to revisit her Sephardic family’s history.

More than a decade later Meerapfel again mined her biography with My German Friend (2012). The film tells the story of Sulamit and Friedrich, who meet as teenagers in 1950s Buenos Aires Their friendship and love are complicated by the reality that Sulamit is the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Germany and Friedrich is the son of German Nazis. The political upheaval of the Left in 1968 Germany and the anti-Leftist General’s Dirty War in Argentina play a big role in the film, complicating Sulamit and Friedrich’s story further. The film is an epic love story that distills 30 years of personal and political postwar history. Partly based on people and events from her own life, writer-director Jeanine Meerapfel delivers a humane examination of a guilt-ridden generation seeking to escape the mistakes and legacy of their parents. Meerapfel states that “the film is my declaration of love to Argentina, the country that welcomed my family into safety, but also to the Germans of my generation who dragged themselves out of the morass of guilt and self-hate, and in so doing have helped to give today’s society a humane face.”

Jeanine Meerapfel has been a member of the Film and Media Arts Section of Germany’s Akademie der Künste since 1998. She was the Deputy Director of this Section from 2012 to 2015. She was elected Director of the Akademie der Künste in 2015 and reelected in May 2018.

In addition to Jeanine Meerapfel, several other Jewish women are creating cinema on Jewish subjects in Germany today. Born in East Germany, Ilona Ziok (b. 1968) managed to escape to the West and continued her career as a highly successful film producer and director with two films on Jewish themes, Auschwitz Love Story (1989) and the widely distributed Kurt Gerron’s Karussell (1999). The latter, a haunting film that includes cabaret performances by some of today’s young German stars and rare archival material from Weimar and Nazi Germany, tells the story of the Jewish actor who played the original Mack the Knife in Kurt Weil and Berthold Brecht’s Threepenny Opera. Together with other Jewish artists and intellectuals, he was eventually sent to Thereisenstadt where he continued to create theater. At Hitler's command, he also directed the propaganda film The Fuhrer Gives the Jews a City (1943), for which he remains infamous. The difficulty of raising finance for such controversial films often led Ziok to question if Germany had truly dealt with the legacy of Nazism. While the German government financially supported her documentary Fritz Bauer: Death by Instalments (2010), all the country's major film funds and main TV broadcasters rejected the project. Fritz Bauer, whose parents were Jewish, was the state attorney who initiated the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial. He also tipped off Israeli Agents that Adolf Eichman, the architect of the Nazi’s final solution, was seeking refuge in Argentina. His efforts paved the way for a more democratic post-War Germany.

England

The politics of power and powerlessness are effectively addressed in the documentary work of Mira Hamermesh (b. 1929 - 2012). Born in Lodz, Poland, she was sent to England by her parents as a young girl, to protect her from the Nazis. Her parents later perished in the Holocaust. She returned to Poland to the famed Lodz film school. Her documentary work focuses on aspects of oppression and injustice, subjects painfully close to her own early experiences. Maids and Madams (1986) bravely addressed apartheid in South Africa with an internationally acclaimed work about South African white women’s relationship to their Black maids. She was one of the first Jewish filmmakers to give voice to the Palestinians in the groundbreaking Talking to the Enemy (1988). The film follows the friendship between Israeli magazine editor Chaim Shur and a Palestinian journalist, Muna Hamzeh. Made just before the outbreak of the first Palestinian Intifada, the film captured the possibility of compassion in one extraordinary moment, when the protagonists weep on each other’s shoulder. Hamermesh returned to her own story of loss in Loving the Dead (1982), in which she goes back to Poland to search for her mother’s grave. Hamermesh’s personal search is mirrored in the efforts of some Poles to recognize the contributions of Jews to Polish life. By loving the dead, they are able to heal the wounds of loss. Hamermesh published her memoir, The River of Angry Dogs, an account of her teenage escape from Poland, in 2004. She was honored in Jerusalem with a retrospective of her work at the Cinematheque in 2005 and passed away in 2012.

British filmmaker and writer Naomi Gryn (b. 1960) preserves memory by documenting the amazing story of her father Rabbi Hugo Gryn’s survival in Auschwitz in the moving Chasing Shadows (1990). In the film, Gryn, a beloved rabbi in England, returns for the first time since 1945 to his hometown of Berehovo, once part of Czechoslovakia. The film creates a picture of an enchanted life at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains—a life that was later destroyed. However, the film is not a lament, but a celebration of the beauty and intensity of Jewish life as it once was. This film stands out among the many made to document the stories of those who survived and those who perished. Naomi Gryn has made a number of other documentaries for British television, including The Sabbath Bride; The Star; The Castle and the Butterfly: The History of the Jews of Prague, and The Last Exodus: The Flight of the Jews from the Soviet Union. In 2000 she published a memoir based on the notes and life of her now deceased father, also entitled Chasing Shadows, which was a critical and commercial success. Her next film was Leon’s Story (2009) about Leon Greenman. Born in the East End of London, Leon was living with his family in the Netherlands when war broke out. Unable to prove their British nationality, Leon’s wife and son were murdered at Auschwitz. Leon survived six concentration camps and, until his death in 2008, spoke to thousands of young people as a witness to the Holocaust, delivering a powerful message against racism. Leon’s Story accompanies the permanent gallery at The Jewish Museum London.

France

In France there are diverse representations of Jewish life by women directors, reflecting their personal narratives Vera Belmont (b. 1934) has been successfully producing films since the early 1960s. The most internationally famous film she produced was Quest for Fire (1981). She turned the camera on her own experience when she wrote and directed her first film, Red Kiss, released in 1985. Set in Paris in 1952, it depicts Nadia, the daughter of Polish-Jewish émigrés, a committed Communist who loves Stalin but is easily corrupted by a handsome young journalist who leads her to the jazz joints of Saint Germaine. Belmont both captures the spirit of the moment and retells her own story of first love in this captivating and steamy story. Several years later, in Milena (1991), Belmont returned to the story of the woman who was best known as Kafka’s lover. A complex, tortured love story set in Vienna and Prague reveals Milena Jesenska, a non-Jew who took an early stand against Hitler and was ultimately killed in a Nazi concentration camp because of her efforts to save Jews. Belmont’s Surviving with the Wolves released in 2007 and was adapted from a suppposed autobiography by Misha Defonseca. Shortly after the release of the film and following a controversy in the press and on the internet, Defonseca was forced to admit that her story was invented. Belmont also apologized for her belief in the story.

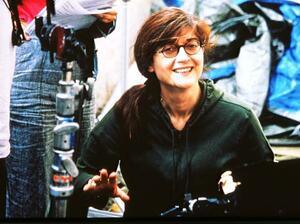

Diane Kurys (b. 1948), one of France’s most successful women filmmakers of the 1980s, had international success (and won the Louis-Delluc prize) with her first film, Peppermint Soda (1977), which enabled her to set up her own production company with her Jewish pied noir (Algerian-born citizens living in France) partner, Alexandre Arcady. Her films constitute a series of interrelated semi-autobiographical fictions, several of which draw, to a greater or lesser extent, on her background as the daughter of separated, non-practicing Russian-born Jews. Peppermint Soda recounts the bittersweet growing-up experiences of two young schoolgirl sisters in the 1960s, including the elder’s growing politicization and awareness of antisemitism, while Cocktail Molotov (1980), set during May 1968, includes scenes of Jewish life in Lyons and tracks the elder sister’s unsuccessful attempt to get to a kibbutz.

Two later films dwell sensitively on the experiences of Kurys’s parents, who met and married in a Vichy detention camp for Jewish refugees during the German occupation of France. Another international hit, At First Sight/Entre Nous (1983), set in Lyons in the 1950s, is prefaced by an enactment of the parents’ encounter, before focusing on the mother’s intimate friendship with a non-Jewish woman, which leads to the breakdown of the marriage. C’est la vie (1990), set during a summer holiday at La Baule Les Pins in the 1950s, reworks the breakdown of the parents’ marriage, but recalls the father’s action in saving both his wife-to-be and her half-sister from deportation. Kurys’s period reconstructions are typically marked by the inscription of socio-political references, which allow the Jewish families to be inscribed into postwar French social history.

Kurys’s more recent work, Sagan (2008), Pour une Feme (2013), and Arrete ton Cinema (2016) revisit themes of illicit love and continue the autobiographical stories that launched her career more than 40 years ago with the seminal Peppermint Soda, which was digitally restored and launched again in New York City in 2018. Speaking about her career, Kurys says, “Four of my movies are telling the same story: about my family, my parents, their divorce. And it comes from being very, very unhappy. The reason is, I was born into a lie about the identity of my real father. After telling that story in For A Woman, it’s obvious that making films is my therapy.” (Hyperallergic, August 13, 2018)

Charlotte Silvera (b. 1954) has made three films, Louise l’insoumise (1985), Prisonnières (1988), and C’est la tangente que je préfere (1998). Her first film, set in the early 1960s and winner of the Georges Sadoul Prize, draws on her own background to provide a stark, realistic portrayal of an uncompromisingly traditional family of Jewish immigrants from Tunisia, seen from the point of view of the rebellious child heroine. In 2011, Silvera completed Escalade, which critics compared to Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 film The Rope because its young characters lack moral scruples when they kidnap their principal. Silvera remains artistically committed to presenting a vision of the world without fear for young people.

Among the more recent generation of Jewish women directors in France, some are children of survivors who migrated there. Others are émigrées from Morocco. Two who stand out are Martine Dugowson (b. 1958), who directed Mina Tanenbaum (1993), Portraits Chinois (1997), and Louba’s Ghost (2000) and Yolande Zauberman, who directed Ivan and Abraham (1993), Clubbed to Death (1997), and La Guerre à Paris (2002).

Dugowson delves into themes of women’s friendship and the passage of time. In her first and third films the young protagonists are born into families of Holocaust survivors. Whether first or second generation, this trauma of their family histories affects the way that they see the world. In Mina Tanenbaum Dugowson juxtaposes the moody artist Mina of Eastern European roots with her best friend Ethel, whose family is from North Africa. Ethel is more social, but her life is weighed down with a feeling of not belonging. Mina and Ethel share friendship in their “outsiderness” but come from different cultures, which dictate their life choices. These themes recur in Louba’s Ghost.

Zauberman worked in documentary film for many years, focusing on the experiences of the oppressed in South Africa in Classified People (1988) and in India in Criminal Caste (1989), before she wrote and directed a remarkable first feature film about shtetl life in Eastern Europe, Ivan and Abraham. Shot in one of the few remaining villages in the Ukraine, Zauberman’s film reflects upon her grandmother’s stories. She chose to shoot in black and white and most of the film is spoken in Yiddish. It is one of the few films that refuse to idealize or sentimentalize shtetl life. The film, which was a commercial success when it was released in Paris in 1993, is a revelation of unshakeable friendship between two boys, one Jewish and one not, who co-exist in the Jewish, Russian, and Romany villages somewhere on the border between Russia and Poland in the tension-wracked 1930s. Clubbed to Death addresses different forms of otherness through the encounter between a young Parisian woman and the world of the multi-ethnic French banlieue, while La Guerre à Paris returns to the question of Jewish identity set during the Occupation.

In 2011, Zauberman presented Would you have sex with an Arab? at the Venice Film Festival. Filmed in Tel Aviv, most of the scenes are shot at night in dance clubs, bars, cafes, and private homes. She chose Tel Aviv as the site for her inquiry because the city feels “guilty of nothing” and “has a certain blindness to it.” Zauberman revealed that she sometimes “felt the incapacity to understand, to realize what happens in the rest of the country.” With Tel Aviv as Israel’s most socially progressive city, the film explores personal attitudes towards “the other” in the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict through this study of attitudes on sex and intimate relationships. The documentary was dedicated to one of the characters in her film, Juliano Mer-Khamis, the Israeli Jewish/Palestinian Arab actor, director, filmmaker, and political activist murdered in front of his Freedom Theatre in the West Bank Palestinian city of Jenin in 2011.

Zauberman used guerilla-style interviews to expose rampant child sexual abuse among the ultra-Orthodox Jews in her next film, M. Shot entirely at night, the film was largely composed of murky close-ups of the victims living in the religious community of B’nei Brak. It won the Locarno Film Festival’s Special Jury prize in 2018. The title is a provocative reference to the German expressionist filmmaker Fritz Lang’s thriller M about a serial child murderer. In this case, Zauberman’s subject, Menahem Lang, felt that his sexual abuse killed his soul.

A more recent phenomenon in France is the turn to documentary as a way of tracking Jewish identity. In Petite conversation familiale (2000), Hélène Lapiower gets her New York family to talk about their family history, while in Le Premier du nom (2000), Sabine Franel traces the genealogy of a Jewish name.

North African Filmmakers in France

France is rich with talented women filmmakers from the North African Jewish communities of Morocco and Tunisia. One of these, Simone Bitton (b. 1955), came from a Moroccan family that immigrated to Israel in the early days of statehood. Simone later moved to France to pursue a career in film, feeling there were few opportunities for North African women to do so in Israel. Bitton is an outspoken advocate for the Mizrahi (North African) underclass in Israel, having personally suffered from the Eurocentrism that, due to class and cultural differences, tried to deny Moroccan identity. Her radical analysis naturally gravitated to the concerns of Palestinians, making the argument that North African Jews, like the Palestinians, feel a sense of oppression as a result of the European colonization of Arab lands. Her films are often a statement of the compatibility of language and traditions between Palestinians and Jews from Arab lands. Early in the 1970s Bitton made a film about the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” which retells the achievement of Israeli independence from the Palestinian point of view. She continued her exploration of Palestinian culture and identity with a short documentary made for French television, about a world-renowned Palestinian poet. Mahmoud Darwich: The Land As Language (1998) gives voice to Darwich with eloquent images that speak of the poet’s separation from his homeland, where he was born in an Arab village that was later eradicated from the map of Israel. The Bomb (2000) is about the families, both Palestinian and Israeli, whose members were killed in a suicide bombing in Jerusalem. Le Mur (2004) is a powerful documentary on the separating fence erected between Palestinian territory and that of Israel.

Rachel is Bitton’s 2009 documentary that presents a comprehensive look at the death of a 23-year-old American peace activist, Rachel Corrie. Corrie was killed by an Israeli military bulldozer in 2003 during a non-violent protest against the demolition of Palestinian homes in Gaza. In Bitton’s words “Rachel is an in-depth cinematic investigation into the death of an unknown young girl, made with a rigor and scope normally reserved for first-rate historical characters. It gives voice to all the people involved in Rachel’s story, from Palestinian and foreign witnesses to Israeli military spokespersons and investigators, doctors, activists and soldiers linked to the affair. Rachel, as a young activist, was convinced that her American nationality would protect her and that her simple presence would save lives, olive trees, wells and houses.”(Berlin Film Festival Catalogue, 2009) Although the premiere at Berlin Film Festival in February 2009 was without controversy, at the San Francisco Jewish film Festival the story was met with controversy, led by rabidly right-wing American Jews and Zionist organizations who attempted to censor the film.

Edna Politi (b. 1948), who moved from her birthplace in Lebanon to Israel and later to France, is of the same generation as Bitton, with a similar readiness to look at the Arab-Israeli conflict. The uniqueness of their vision derives from their being Arab Jews. Her dramatic film, Like the Sea and Its Waves (1980), shows a willingness to hear the pain of her Palestinian women friends as they sit in Paris cafés and return to the Middle East to hear each other’s stories. At the time, this was unprecedented in the world of cinema on Jewish subjects. As an Arab Jew, Politi takes an interest in early Zionism and the feminist aspirations of Eastern European women in a follow-up and now classic documentary, Anou Banou: The Daughters of Utopia (1982). Sometimes humorous, at other times poignant, Anou Banou gives insight into the hopes and dreams of socialist, Zionist, and feminist women arriving in Palestine in the 1920s and talking about their lives 60 years later. Politi currently lives and works in Switzerland. Later in her career she was curious about music and musicians. The Quartet of the Possibles (1992), an elegant meditation on music and metaphysics, and a bio pic entitled Paul Sacher, The Musician Patron (2001) were among her most significant works on this topic.

Charlotte Szlovak’s (b. 1947) family emigrated from Hungary to Oujda in Morocco before World War II. She tells the stories of her family’s experiences in Doctor Szlovak (1995) and Return to Oujda (1987), works that explore the unique Judeo-Arabic culture of her birthplace. Her approach is from the vantage point of a young woman returning, after she immigrated to France, to relive her family history by visiting her parents’ house, the city streets, and surrounding countryside. Bringing memory to life, she renews ties of friendship that existed for generations between Jews who left and Jews who stayed and between Jews and Muslims, painting a picture of coexistence in its best sense.

Izza Genini (b. 1942) is the premier documentarian of Moroccan musical traditions and anthropology. Many of her films are about the Jewish influence in the vast North African culture from which she came. In Return to Oulad Moumen (1994), Genini relates through the narrative voice of her now deceased mother the history and migrations of her Moroccan Jewish family. She explores the shared musical traditions of Muslims and Jews with the mystical songs of the Matruz tradition. With its Andalusian roots, Matruz is a shared Muslim-Jewish musical form that fuses Arab and Hebrew poetry, reflecting the centuries-old link between Jewish and Muslim societies in North Africa.

Several commercially successful films about Tunisian Jews in the garment industry give the audience a glimpse of the identity issues and cultural differences between North African Jews and their European co-religionists and between them and traditional French culture. All of these films were made by men and are fraught with standard—frequently offensive—stereotypes of Jews. In contrast, Tunisian-French director Karin Albou (b. 1969) describes the transformation of Judeo-Arabic culture from Tunisia to Paris. Due to the repercussions of the Israeli-Arab conflict, many Jews from Tunisia, a former French colony, resettled in France. The specificity of the group’s culture shock is explored in the documentary My Country Left Me (1995). Most of the characters remember Tunisia fondly but speak of the pain of suddenly becoming outcasts in their own land. Young Jews, who are as French as they are Tunisian, talk about the emergence of their identity in the mosaic of contemporary France. France’s Jewish population, the largest in Europe, is unique in that the numbers of Ashkenazi and North African Jews are almost equal.

Albou boldly walks into dramatic feature filmmaking as Director/Writer of The Wedding Song. Set in Tunis, 1942 it is about two teenagers friends living in a neighborhood where Jews and Muslims live in harmony. When the German army enters Tunis, both their lives and dreams are disrupted with the Nazis pursuit in the destruction of the Jewish community. Albou performs in her next film that she also wrote and directed; My Shortest Love Affair. A mature drama and hilarious tale of relationships, sex and starting over, Louisa and Charles re-meet in their forties and after a drunken night, get pregnant.

Belgium

Two other outstanding filmmakers are the Belgians Chantal Akerman (1950-2014) and Diane Perelsztein (b. 1959). Akerman was a pioneer of feminist and experimental film and a very prolific artist. While she made her mark on the international cinema scene with the feminist film Jeanne Dielmann (1975), she explored aspects of her Jewish identity in American Stories: Food, Family and Philosophy (1988), in which she turned her camera on Jewish New York with a humor that reveals the kitsch as well as the angst of the New York Jewish experience. She also refers autobiographically to her own experience in a short narrative film about first love.

Akerman’s family story is compelling. Her Jewish father was in hiding during World War II, while her mother was the only member of her family to survive Auschwitz. She readily acknowledged that she was influenced by her parents’ experiences during and after the war. All told, Akerman directed more than 40 films, including Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974; she also played the lead), the musical Golden Eighties (1986), and the comedy A Couch in New York (1996), as well as documentaries and video installations. In her final work, No Home Movie (2015), she presents a conversation with her mother recorded shortly before her death in 2014. Akerman, who had long struggled with depression, committed suicide following her mother’s death.

Diane Perelsztein references the exile of Jews and brings to light the experiences of the Jews of Shanghai in Escape to the Rising Sun (1990), shot in April 1989, just weeks before the massacre of Tiananmen Square. This was the first time a film crew had been allowed into the poor neighborhood of Hongkew, where Jewish refugees from WWII lived. Twenty thousand Jews escaping Nazi persecution took refuge in Shanghai, the only place in the world that did not require entrance visas. Veteran German filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger (b. 1942) expanded this subject further with an epic five-hour documentary, Exile Shanghai (1997), that includes the stories of Jewish emigrants who arrived even earlier, using a meditative camera that reflects upon life in Shanghai today.

Perelsztein’s Rhodes Forever (1995), a history of the Jews of Rhodes and their eventual destruction and exile, is the first documentary devoted to the Jews of that island. Retracing the history of the Jews from Spain to their refuge in Rhodes after their expulsion in the fifteenth century, she uses song and wonderful archival footage of a bustling Jewish quarter, a traditional wedding, and intimate interviews with the survivors of Rhodes after World War II, who still speak Ladino. Collaborating with brother Willie, her career continued with works that explored tea and an opera singer. In Hughes Lanneau’s Modus Operandi (2008), she co-wrote the story of the 24,916 Jews who were deported from Belgium to Auschwitz between 1942 and 1944. The roundups and deportations were organized and carried out by the Nazis with the cooperation of Belgian authorities. The attitude of the authorities here varied from outright resistance to voluntary or unwitting collaboration.

Conclusion

One can perceive the body of work created by Jewish women filmmakers in Europe as a testament to the efforts of Jews to re-calibrate community and family in the years following the traumas of World War II. These films preserved for future generations family histories, immigrant stories, and the memory of those who perished. More recent films explore the identities of women in the modern generation, where they have a wider variety of choices. While the memory of the Holocaust still looms in the psyche, new themes—of intergenerational relations, acculturation of immigrants into new societies and exploration of the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinians—come into focus. One can confidently look forward to new works by women film artists that reflect the reality of the lives of Jews in Europe today.

Thanks to Carrie Tarr for her research and assistance.