Modern Dance Performance in the United States

Jewish immigrants to the New World brought with them their ritual and celebratory Jewish dances, but these traditional forms of Jewish dance waned in the United States, as youth were influenced to Americanize and assimilate. Working-class and poor Jewish immigrant parents, however, sought out culture and education in the arts for their children, often as a vehicle for assimilation. Jewish women were particularly attracted to the field of modern dance and were trained by canonic dance personalities, companies, and institutions, including Isadora Duncan and her Isadorables, Denishawn, the Martha Graham Dance Company, the Humphrey-Weidman Company, Alwin Nikolais, the New Dance Group, the Dance Theater Workshop, and Judson Dance Theater. In turn, Jewish women became modern dance performers, teachers, choreographers, company directors, costumers, lighting designers, critics, writers, and researchers.

Introduction

Dance has always played an important role within Jewish communal traditions because of its capacity to heighten both the collective and individual joy. Dancing in Judaism can be traced to both written and oral traditions. The Bible contains many dance images (from Miriam dancing with the Israelite women in victory to King David) described with eleven different and specific Hebrew dance terms. In written The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.Halakhah there are rabbinic commentaries in the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud and the Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.Responsa, not only how to dance at a wedding (Ketubot Tractate 17A), but also descriptions, for example, of the most joyous dance ever seen (at Sukkot). Different interpretations of how to execute dances in different communities over time account for the rich differences in Diasporic community dance at weddings, holidays, and even in prayer.

Jewish immigrants brought with them their ritual and celebratory Jewish dances, but these traditional forms of Jewish dance waned in the United States as youth were influenced to Americanize and assimilate. Settlement houses, social institutions, as well as political movements such as Socialism, Communism, and Zionism all affected the changes. In New York from the 1910s through the 1950s, these influences included Zionist and Yiddish groups such as He-Haluz ha-Za’ir, Camp Kinderland and Camp Boiberik, Henry Street Settlement House, the Neighborhood Playhouse, the 92nd Street Y, and the New Dance Group. Nonetheless, the bond between dance and Judaism remained strong, particularly as young women began to express themselves through the art of dance.

Jewish women were particularly attracted to the field of modern dance. The development of the American modern dance movement from the 1920s through the 1960s centered in New York City, which was also the site of America’s largest Jewish community. Working-class and poor Jewish immigrant parents on the Lower East Side sought out culture and education in the arts for their children, often as a vehicle for assimilation. Ironically, many of these same parents disapproved when dance became their children’s chosen profession.

Canonic dance personalities, companies, and institutions trained Jewish dancers including Isadora Duncan and her Isadorables; the Denishawn Company; the Martha Graham Dance Company; the Humphrey-Weidman Company; Henry Street under Alwin Nikolais; the New Dance Group, and later, the Dance Theater Workshop and the experimental Judson Dance Theater. In turn, Jewish women became modern dance performers, teachers, choreographers, company directors, costumers, lighting designers, as well as critics, writers, and researchers. The latter, almost a century later, created “Jewish Dance Studies" within academia.

Duncan Dancers

Julia Levien (1911- 2006) was born to Rashel Wetrinsky, a Yiddish poet, and Benjamin Levien, both from Russia. Considered one of the premier teachers of the Isadora Duncan dance style, Levien began as one of the core performers in the company of Duncan’s adopted daughter Irma. (The others, also Jewish, were Sonja Gaze, Mignon Garlin, Ruth Fletcher, and Hortense Kooluris.) Levien also choreographed for the Yiddish Folksbiene (or “People’s Stage,” part of the Workmen’s Circle Theater Project), partnered Benjamin Zemach on United States tours, and taught at Camp Boiberik and the Sholom Aleichem House of Cooperative Living in New York City.

Annabelle (née Gold) Gamson (b. 1928), a student of Levien, danced on Broadway in Jerome Robbins’s On the Town and Finian’s Rainbow, and occasionally performed with Anna Sokolow and American Ballet Theatre, but she is best known as a Duncan interpreter.

Nadia Chilkovsky Nahumck (1908-2006) studied at the Philadelphia Duncan studio of Jewish dancer Riva Hoffman, who had studied with Duncan in Europe and at the time was considered the only formal United States teacher of the Isadora Duncan style. After Duncan’s death, arts manager Sol Hurok produced a children’s performance tour in America under Irma Duncan, who chose Chilkovsky as one of the children. Later Chilkovsky studied with Hanya Holm and became a Labanotation expert, writing several Laban books. She also founded the Philadelphia Dance Academy, which eventually became part of the University of the Arts. In 1934, Chilkovsky attended a rally of the unemployed with Miriam Blecher, where a young organizer was slain by the New Jersey police; the events inspired the dancers to launch the New Dance Group, a working-class organization with the slogan “Dance is a weapon in the class struggle.”

Henry Street Settlement and the Neighborhood Playhouse

The Henry Street Settlement on New York’s Lower East Side offered many programs to American immigrants, including dance classes. Wealthy German-Jewish sisters Irene Lewisohn (1892-1844) and Alice Lewisohn (c. 1883–1972) had dance and theater training (both studied the Delsarte system with the American proponent Genevieve Stebbins; Irene also observed at the European Hellerau Dalcroze School), but their Orthodox Jewish father dissuaded them from stage careers, emphasizing philanthropy instead, especially at the Henry Street Settlement. Around 1905, the sisters began teaching dance and drama there, eventually creating seasonal festivals using pantomime, dance, and song, including Three Impressions of Spring, Miriam, a A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover festival, and Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah festivals. In 1915, they expanded arts programming by building the Neighborhood Playhouse several blocks away at 466 Grand Street. The New York Times covered the Playhouse’s productions, such as Jephthah’s Daughter, saying such works “revitalize and interpret their own traditions and symbols.” Other works included The Dybbuk, and in 1928 Irene Lewisohn staged Ernest Bloch’s Israel Symphony.

Blanche Talmud (c. 1900–c. 1990) lived in the neighborhood, grew up performing in the settlement festivals, and eventually became the Neighborhood Playhouse’s core dance teacher. Talmud had also studied Dalcroze eurhythmics in Paris and performed in Adolf Bolm’s Ballet Intime and in the 1917 Roshanara Chorus. After 1931, she also appeared in Humphrey-Weidman productions. Students in Talmud’s Playhouse classes included Anna Sokolow, Sophie Maslow, Helen Tamiris, Lillian Shapero, Edith Segal and Jean Rosenthal, who all relished the “special atmosphere in Talmud’s dancing classes where the cramped quarters and the other grim realities of tenement life might temporarily be forgotten.” Most of the principle dancers in agit-prop or leftist populist workers’ dance were Talmud’s students, who championed minorities such as African-Americans, Okies (migrant agricultural workers), workers trying to unionize, and anti-Fascists (Graff 21, 27).

Edith Segal (1902–1997) danced at the Neighborhood Playhouse. She also performed with Michael Mordkin and then created her own work, despite her immigrant mother calling her a bummarke (bum) for dancing. Segal’s 1930 pageant The Belt Goes Red—celebrating the Soviet Union, which she visited the following year—was performed at Madison Square Garden. Due to her Communist politics, she was refused bookings at the important dance venue of the 92nd Street Y. Segal often used Yiddish songs or Jewish music to accompany her dances. A Jewish Family Portrait, accompanied by a wordless melody niggun, depicted an Ashkenazic family coming alive as if from a posed photograph. She used Jewish themes, she said, to counteract anti-Semitism, and she believed working people watching her dances could help preserve Yiddish culture. Segal made her living teaching dance in Yiddish secular schools, occasionally performing, and teaching every summer from the 1930s to the 1970s at Camp Kinderland.

Helen Tamiris (c.1905-1966) began dancing with Lewisohn and Talmud at the Neighborhood Playhouse because her brother urged their widower father to give her dance classes to get her off the streets (Studies in Dance History 4-7). She later studied ballet at the Metropolitan Opera and with Mikhail Fokine before joining the Metropolitan Opera ballet chorus. Her concert dance career began in 1927 and rapidly established her as one of the premier modern choreographers. In 1930 she organized a repertory company for two seasons with choreographers Graham, Humphrey, and Weidman, then launched the Tamiris Group and school. Although she rarely used Jewish themes in her work, her dances reflected a commitment to social justice that she learned growing up in her poor Jewish family. She also taught for Elia Kazan at his Group Theater. Tamiris was one of the first white choreographers to depict aspects of black life, in her early works How Long Brethren? and Negro Spirituals. Decades after their creation, though controversial regarding expression of Black culture, in 1995, these works set audiences cheering at the American Dance Festival (ADF). Tamiris is perhaps most noted for her remarkable Broadway career, choreographing eighteen shows including Showboat (1946); Park Avenue (1946); Inside USA (1948), the Tony award-winning Touch and Go (1949), Great to Be Alive, Bless You All (1950), and The Lady From Colorado (1964). In the Broadway musicals she choreographed, she used “colorblind” casting, giving opportunities to many who would otherwise not been given work at that time. She received Dance Magazine Awards in 1937 and 1950 and was posthumously granted the ADF Scripps Award.

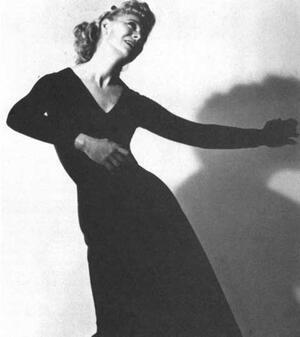

Pauline Koner (1912-2001) was born to Russian immigrants who considered themselves Jewish intellectuals and were part of New York Yiddish cultural circles. Her father, Samuel, devised a pioneering group medical plan for the Workmen’s Circle. Koner started at the Neighborhood Playhouse, although she came to prefer studying with ballet master Mikhail Fokine and others, including Michio Ito. Her Jewish background included memories of dancing with her grandfather on Lit. "rejoicing of the Torah." Holiday held on the final day of Sukkot to celebrate the completing (and recommencing) of the annual cycle of the reading of the Torah (Pentateuch), which is divided into portions one of which is read every Sabbath throughout the year.Simhat Torah on the Lower East Side, with the observant men parading, holding flags, and dancing with the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah scrolls. By the time she was fourteen years old she was teaching dance at the Workmen’s Circle summer camp.

Koner, who saw herself as a loner, did not join the left-wing groups or dance companies of her time. Instead she created solo concerts and had success touring. She occasionally drew on Jewish ideas: her piece Voice in the Wilderness takes its text from Isaiah. Koner’s friend and fellow Jewish dancer Corinne Chochem influenced Koner to travel to Palestine from 1932 to 1933; Koner also danced in Egypt and traveled to the Soviet Union in 1936. In 1945 she performed at the 92nd Street Y, where she met Doris Humphrey (who had just begun directing the Y’s dance education department), who invited her to dance with her company and with Humphrey protégé José Limón. Koner became a soloist with the Limón company from 1946 to 1960. Stylistically versatile, she also contributed to early television dance, taught dance around the world, and choreographed stage shows at the Roxy Theater and several ice revues. Although usually categorized as a modern dancer, she was fond of saying, “I never had a modern dance lesson in my life.” In 1964 Koner received the Dance Magazine Award and a Fulbright fellowship to teach in Japan. In 1979 she staged Cantigas for Israel’s Batsheva company. In 1985 she was awarded an honorary doctorate of fine arts by the University of Rhode Island.

Denishawn

The iconic Denishawn, created by Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis, was considered the foundation of American modern dance. Denishawn discriminated against Jews through their quota systems on both East and West coasts. Nonetheless, Klarna Pinska, raised in a Winnipeg Jewish family, moved to California to work for St. Denis as a maid in exchange for classes. Pinska became a St. Denis protégée, eventually teaching in the 1920s and 1930s in Denishawn schools in Los Angeles and New York. Years later, she restaged Denishawn works for new audiences in New York for the Joyce Trisler Dance Company.

The Graham Company

Martha Graham did not share the anti-Semitism of Denishawn. After she broke away, her company dances by the 1930s included Jewish dancers, especially from her dance classes at the Neighborhood Playhouse. From this group emerged Jewish choreographers such as Sophie Maslow, Anna Sokolow, Lillian Shapero, and Lily Mehlman. These Graham dancers also joined the Workers Dance League and in 1934 produced a concert in support of better wages.

Among many Jewish Graham dancers were Isabel Fisher, Nelle Fisher, Elizabeth Halpern, Lili Mann, Marjorie (née Mazia) Guthrie (1917-1983), who assisted Graham for fifteen years, and Miriam Cole (1926-2012). Gertrude Shurr (1904-1992) left Denishawn first to dance with Humphrey, then became Graham’s assistant and went on to teach at the High School of Performing Arts in New York. Freda Flier Maddow (1917-2004) who had performed with Benjamin Zemach, danced with Graham from 1937-1941 then returned to dance in Los Angeles. Marie Marchowsky (1917-1997) joined the New Dance Group after dancing with both Graham and Sokolow. Other Graham dancers included Thelma Babitz, Sydney Brenner, Mattie Haim, Pauline Nelson, Frima Nadler, Nina Caiserman, and Netanya Neuman.

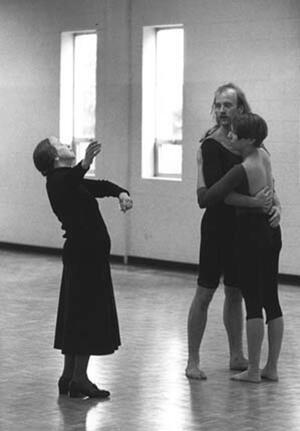

Anna Sokolow (1910-2000) grew up on the Lower East Side in the heart of the Jewish ghetto. Her personal experiences of poverty affected her ideas of social justice, later reflected in her choreography and politics. Sokolow joined Graham’s company in 1930 and stayed until 1939, also performing in her own work. She collaborated with the New Dance League, whose Jewish dancers included Sophie Maslow and Lily Mehlman.

In the 1940s Sokolow began to explore her Jewish heritage, creating Lit. (Aramaic) "holy." Doxology, mostly in Aramaic, recited at the close of sections of the prayer service. The mourner's Kaddish is recited at prescribed times by one who has lost an immediate family member. The prayer traditionally requires the presence of ten adult males.Kaddish (1945), The Dybbuk (1951), Rooms (1955), and later, her elegy for the Holocaust, Dreams (1961). She also created a Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim pageant (1952) and an Israel Bonds program in Madison Square Garden (1953). In 1953, through Jerome Robbins, Sokolow was sent to Israel to coach the Israeli Yemenite Jewish dancers of the new Inbal Dance Theatre Company, directed by Sara Levi-Tanai. Sokolow taught modern dance technique and stagecraft, returning for several years to help mold the company for its international tours. While in Israel, Sokolow also choreographed for a small repertory company called Bamat Mahol and established her own company, the Lyric Theater (1963–1964). Ze’eva Cohen, [link to new entry on Ze’eva Cohen] who had first trained with Gertrud Kraus, met Sokolow at Bamat Mahol, then joined Sokolow’s company and later followed her to New York (see below for more information on Cohen’s career). Historian Hannah Kosstrin describes Sokolow’s Rooms, choreographed in 1954, as “challenging Cold War social hierarchies…(with so many) living under government surveillance” (Kosstrin 185). Sokolow staged some of her dances for the Batsheva Dance Company, including her Holocaust work, on her return trip to Israel in 1973, which was cut short by the Yom Kippur War. Sokolow at the end of her life was “caught between shifting generations…an old communist who became known again as a voice of the counterculture…The honest bodies in Sokolow’s works propelled her activism to repair the world” (Kosstrin, 230).

Sophie Maslow, like Sokolow, Segal, and Koner, had started dancing at the Neighborhood Playhouse in Blanche Talmud’s classes. Maslow remembers dancing as a child in Irene Lewisohn’s orchestral production Israel, which gave Maslow her first glimpse of Martha Graham, with whom she also studied in the Playhouse’s three-year course of conservatory-style arts program. Like Sokolow, Maslow went from the Neighborhood Playhouse to the Graham Company. During her eleven years with the company, she also began choreographing her own works. She taught Graham technique for the New Dance Group and formed her first company with some of her students there, including Muriel Manings, Anneliese Widman, and Rena Gluck (who moved to Israel, was a founding member of the Batsheva Company and directed the dance program of the Rubin Academy). Programs and choreography by Maslow were seen at the New Dance Group and the 92nd Street Y. Her Hanukkah celebrations from 1951 to 1970 at Madison Square Garden were supported by Israel Bonds; not “simply political rallies, …they were large-scale performance events about and for Israel,…a secular and communal holiday tradition with a civic and economic purpose…consistently sold-out houses of 18,000-20,000 people per show. Maslow’s…choreography for the Chanukah (sic) Festivals created a symbiotic relationship between American modern dance and the modern Jewish state, reflecting the complex bond and demonstrating the political, cultural, economic and aesthetic impact that dance had upon American Jews and Zionist enterprises at mid-century” (Rossen, 204-206). Maslow’s works most associated with Jewish themes are The Village I Knew, based on Sholom Aleichem tales, featuring an interracial cast, and The Dybbuk.

Nina Fonaroff (1914-2003), who began studying ballet with Mikhail Fokine, was with Graham’s company from 1937 to 1946 becoming a soloist and then assisting Louis Horst in his classes (1937–1952). She began choreographing in 1942 and had her own company from 1945 to 1953. She taught at Columbia University Teachers College, Bennington College, and the Neighborhood Playhouse, then moved to England to teach at the London School of Contemporary Dance, later developing movement classes for actors.

Pearl Lang (née Lack; 1921-2009) grew up in Chicago in a socialist home, rich in Jewish culture. She was educated in the Workmen’s Circle Yiddish schools. When she was eight, Lang’s mother introduced her to dance. Later Lang received a Graham school scholarship to New York and joined the Graham company in 1941 until 1952. Because of her charisma and technical prowess, she performed leading roles in Graham masterpieces and took over Graham’s main roles. In 1952, Lang created her first group work, Song of Deborah. She choreographed over 50 works, the majority on Jewish themes. One of her best-known was Shirah (1960), based on a mystical Hasidic tale of rebirth. Her company performed throughout the United States and in Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark, Israel, and Canada. She also choreographed for the Boston Ballet, the Netherlands National Ballet, and Israel’s Batsheva Dance Company. Her awards included two Guggenheim Fellowships, the National Foundation for Jewish Culture’s Jewish Cultural Achievement Award in 1992, and an honorary doctorate from Juilliard in 1995. In 2000 she returned to the Graham school as one of its master teachers.

After performing in Graham’s company, Linda Margolies Hodes (b. 1933) was given the responsibility of overseeing the Graham repertoire donated to the Batsheva Dance Company; after a decade, her departure from Israel coincided with Batsheva de Rothschild withdrawing financial support in 1974. Without Hodes, the Graham repertoire could no longer be performed. In New York again, Hodes directed Paul Taylor’s second company and school; she also served as rehearsal director of other modern dance companies.

The Humphrey-Weidman Company

Like Graham, Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman began their careers at Denishawn and specifically decided to leave because of anti-Semitism. Their company, from 1928 through the 1940s, was welcoming to Jewish dancers. Gertrude Shurr, who went on to dance with both Graham and Humphrey, remarked: “The reason I went with Doris (Humphrey) and Charles (Weidman) when they left Denishawn was because they stuck up for us. Here we were, all of us New York City kids, all of us Jewish kids …and we thought we were going to be taken into the company. And only one tenth of the company could be first generation American. Everybody else had to be from the Mayflower. … I must say Doris and Charles left because of that issue. And we left with them. About fifty-eight people left the school just like that” (Graff 20). Humphrey’s later troupe also included many Jewish dancers: Beatrice Seckler, Eva (née Garnet) Desca, Saida Gerrard (1913- 2005), Joan Levy Bernstein, Marion Scott, and Eleanor Schiel.

The 92nd Street Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association

New York’s 92nd Street Y was a major uptown venue for both dance education and performance. The dance offerings at the Y were varied, including classes in modern, ballet, tap, ballroom, Israeli and Jewish dance; it also served as a showcase for performers and resident companies. The “Auditions,” a yearly competition at the Y, promoted young modern dancers, and the winner was awarded a fully produced performance. Many Jewish dancers were featured: Naomi Aleh-Leaf, newly arrived from Palestine in 1940; Nina Caiserman; Miriam Cole; Emily Frankel; Emily Gluck; Rena Gluck; Ann (later Anna) Halprin; Rheba Koren; and Nona Shurman, from Humphrey’s company. Trudy Goth produced a series at the Y she called the Choreographers Workshop. Katya Delakova and Fred Berk’s Jewish Dance Guild frequently performed there, featuring Shulamit Kivel who had escaped Belgium during the Holocaust and went on to teach Israeli folk dance at the Y. Some fifteen of Anna Sokolow’s programs were presented between April 1936 and 1961. Other choreographers included Pauline Koner, Nina Fonaroff, Hadassah (her dance Shuvi Nafshi premiered in 1947), Gloria Neuman (1951), Judith Martin and Company (1952), Marie Marchowsky (1952), Linda Margolies Hodes, Pearl Lang (whose Song of Deborah premiered there in 1948), and Frances Alenikoff.

Fred Berk created the Jewish Dance Department at the Y and from the beginning he emphasized dance with Jewish themes and Israeli folk dance. He formed the Hebraica Co. at the Y among others featuring Livia Drapkin (who went on to create the Vanover Caravan Dance Co.). Berk’s Jewish Dance Department was separate from the Dance Education Department headed by the non-Jewish Doris Humphrey. Following Humphrey, Lucile Brahms Nathanson (d. 1992), who had danced with Humphrey-Weidman, directed the Dance Education Department. Other directors included Joan Finkelstein who enhanced the Education Department through the Harkness Foundation. From the 1930s through 1969, “the specific meeting of the dance and Jewish communities …expanded into a full-fledged program of classes and performances that emphasized contemporary art and ideas, at a time when Jews were beginning to transfer their intellectual and creative energy away from religion to contemporary arts and ideas” (Jackson 7). With more than 450 dance performances, the Y was significant in validating modern dance as an art form (Jackson 55). The resident company at the Y was the Merry-Go-Rounders, directed by Berk and non-Jewish dancers Bonnie Bird and Doris Humphrey. Bernice Mendelsohn wrote scripts to appeal to families with children; she also served as production coordinator and narrator-dancer. Performers included Barbara Shivitz, Rima Sokoloff, Roberta Singer, and Gloria Spivak. Laurie Freedman (b. 1945), who joined later, went on to perform with the Batsheva Dance Company in Israel from 1968 to 1986 before returning to the East Coast to teach and choreograph.

Ruth Goodman (b. 1950) has directed the 92nd St Y’s Israeli Dance Division (formerly the Jewish Dance Division) with Danny Uziel since 1978, developing the work begun by Fred Berk. A specialist in Israeli folk dance, Goodman maintains Israeli folk dance classes attended by hundreds, a teacher training program in Israeli folk dance, and Israeli folk dance performances. She also directs her own performance company, Parparim (Butterflies), and the Israeli Dance Institute (IDI). Through the IDI, she continues the annual Israel Folk Dance Festivals she has directed since 1978. She produced an international Israeli folk dance festival with Uziel, Horati, at Hofstra University in 2001 and at Queens College in 2018. Goodman also edits IDI’s Hebrew/English Israeli folk dance publication, Rokdim-Nirkoda. Goodman began her dance studies at the Metropolitan Opera School of Ballet and with ballet master Alfredo Corvino; she received her Master of Arts degree in dance education from Columbia University Teachers College.

Working-Class Advocacy, Agitprop Dance, and the New Dance Group

During the Depression, when the federal government supported the arts through the Works Project (WPA), Helen Tamiris was instrumental in making dance a part of the Federal Theater Project (FTP). In 1935, she convinced Hallie Flanagan, the FTP director, to create the Federal Dance Project. Many of Tamiris’ WPA dancers were Jewish, including Paula Bass, Pauline Bubrick (Tish), Florence Cheasnov, Mura Dehn, Fanya Geltman, Klarna Pinska, Selma Rubin, and Sue Ramos.

During this period, many Jewish dancers who allied themselves with the working class, some leftist and others communists, began to choreograph using themes of class struggle and issues of survival, developing the genre of agitprop dance. Dancer and dance critic Edna Ocko (1908-2005) championed these dancers’ art and causes. Felicia Sorel (1904–1972), who worked in the WPA, was trained by Mikhail Fokine and danced at Radio City Music Hall. She became involved in, and eventually director of, the WPA Music Project’s Opera Division. After the war she created theater works, including a television production of The Dybbuk for CBS in 1949.

In her history of radical dance in America, Ellen Graff writes that of all the “revolutionary groups that had flourished at the beginning of the 1930s, only the New Dance Group had a continuous history from the 1940s through the 1970s,” functioning for recreational students and for professionals and “as a producing agent for choreographers committed to dance making with a social and political conscience” (159). The studio, directed by Judith Delman from 1939 to 1966, supported several of the radical Jewish dancers, ensuring them income from teaching and working together in an idealistic, cooperative way. Together with associated schools in several cities, the New Dance Group founders (including Chilkovsky and Ocko) wanted to provide inexpensive classes to spread modern dance as a viable weapon for working-class struggles.

The New Dance Group’s performing arm began as part of the Workers Dance League, with choreographers including Sophie Maslow and Anna Sokolow. In 1953 New Dance Group Presentations produced a festival of works at the Ziegfeld Broadway theater that depicted some Jewish themes, as Graff described, “Jewish themes had been part of the workers’ dance movement from the beginning. … Among active choreographers during the post-war years, some seemed specifically and exclusively tied to working with the traditions of Jewish life and within a folk genre” (Graff 164).

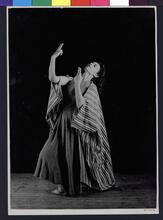

The New Dance Group offered different modern dance techniques, as well as ethnic dance forms with a real social agenda: racially mixed, and very inexpensive classes costing ten cents, so that no one was excluded. The director of the New Dance Group’s ethnic dance department was an unusual dancer, Hadassah (Spira Epstein) (b. Jerusalem 1909, d. New York 1992). She came to New York in 1938 and studied with Jack Cole, La Meri, Nala Najan, and others from India and the Far East, where she traveled extensively. Her own programs in Israeli, Javanese, Indian, and Balinese dance styles were seen from 1945 until the mid-1970s. Her best-known work, Shuvi Nafshi (Return, O My Soul), based on Psalm 116, premiered at the 92nd Street Y in 1947. She performed it several summer seasons at Jacob’s Pillow and was one of the few Jewish dancers favored by Pillow director Ted Shawn. Other dances with Jewish themes included her Israeli Suite, The Cantor, The Wanderer, and Water.

Muriel Manings (1923-2018) came of age when various dance, theater, and other artistic groups infused their work with social and political causes. She joined The New Dance Group and became one of its prominent teachers by the mid-1940s. On June 11, 1993 she organized a gala for the American Dance Guild featuring works from the 1930s through the 1970s, many from the New Dance Group choreographers, at LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Performing Arts in Manhattan.

Hanya Holm Dancers

Gentile modern dance pioneer Hanya Holm, who came to New York from the German expressionist dance company of Mary Wigman, included several Jewish students and company performers: Rheba Koren, Rebecca Stein (who also taught at the New Dance Group), Geula Greenblatt Abrams, Peggy Berg, Nahami Abdell, Mimi Kagan Kim, who appeared in Holm’s work Trend, and Marva Spielman. When Holm dissociated herself from Wigman’s Nazi politics, Spielman returned to dance with Holm, and then made her career in New England.

Holm’s most illustrious Jewish performer was Eve Gentry, née Henrietta Greenwood (1909–1994), the daughter of a Polish Jewish family. She first studied in Los Angeles at the Pavley-Okrainsky Ballet School and studied modern dance with Ann Mundstok in San Francisco and with Harald Kreutzberg. In 1936 she moved to New York, where she danced in Holm’s company for six years, appearing in Holm’s Bennington performances, originating roles in all Holm’s major works of that period: Trend, A Cry Rises from the Land, Salvation, Two Primitive Rhythms, and Dance of Work and Play. Gentry choreographed her own works at the New Dance Group, such as Tenant of the Street (1938). From 1944 to 1968 she had her own company in New York City while teaching at the High School for Performing Arts and the New Dance Group. She was also one of the founding members of the Dance Notation Bureau, served on the dance faculty of New York University, and worked with Joseph H. Pilates for over twenty years. In 1968 she opened her own dance and Pilates center in Santa Fe, co-founding The Institute for Pilates Method. In 1979 she received the Pioneer of Modern Dance Award from Bennington College.

Henry Street Playhouse’s Later Era on the Lower East Side

In 1948, Alwin Nikolais, recommended by Hanya Holm, became director of the Playhouse classes at Henry Street and later the Playhouse Dance Co. which featured several Jewish dancers. He had trained with Truda Kaschmann besides Holm. From the beginning his classes at Henry Street included choreography; his students were Phyllis Lamhut (b. 1933) and Gladys Bailin (b.1930), both later featured in Nikolais’s company works, Lamhut for twenty years. She had her own company earning sixteen choreography fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts plus a Guggenheim Fellowship. Lamhut has become a valued composition teacher, especially at the Tisch School for the Arts at New York University. After dancing with Nikolais, Bailin also danced with Murray Louis and has directed the Ohio University School of Dance. Shown at the Henry Street Playhouse were many young choreographers including Ellida Geyra before she moved to Israel.

Additional Dancers Working with Jewish Themes

Noami Halpern Aleh-Leaf (b. 1918 in The Land of IsraelErez Israel) performed original solos inspired by Jewish and Zionist themes in New York and for several decades after the establishment of Israel. Her extensive but uncatalogued collection of articles and costumes resides in the YIVO archives in New York.

Lillian Shapero (1908–1988) was born into the observant Hasidic family of Jennie and Morris Shapero but raised by her grandparents after her mother died. She always joined her grandfather in his little synagogue, where he encouraged her to participate in the singing and dancing. After studying at the Neighborhood Playhouse and with Bird Larson and Michio Ito, she became a member of the first Martha Graham Dance Theater Company from 1929 until 1935, dancing the solo role in Graham’s Primitive Mysteries. In 1933 she choreographed for Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theater production Yoshe Kalb; their association continued with The Wise Men of Chelm, The Water Carrier, The Three Gifts, The Dybbuk, and other works. In addition to Jewish themes, Shapero used political themes in her Dance for Spain—No Pasaran in the 1930s. She toured widely and performed in Paris, London, and Moscow, where she was a guest of the Soviet Theater Festival in 1937. She also performed at Carnegie Hall in 1952; Maurice Ruach, as conductor of the Jewish People’s Philharmonic Chorus, provided the accompaniment. In the 1960s Shapero, by now considered an authority on Jewish dance, traveled to Cleveland to stage a Jewish Community Center production of The Dybbuk

Dvora Lapson (1907-1996) studied ballet with Fokine and Duncan dance with Irma Duncan; she began her solo career in the 1930s emphasizing Hasidic style and Jewish dance themes. She researched Jewish dance and performed in Poland immediately before the Nazi scourge and traveled to Israel for the first time in 1949. An influential teacher, she directed the Dance Education Department of the Board of Jewish Education in New York for many years, influencing a network of teachers and students. She wrote several booklets in the 1950s and 1960s, including Dances of the Jewish People, Folk Dances for Jewish Festivals, Jewish Dances the Year Round, and The Bible in Dance. She also taught at Hebrew Union College in New York and coached the dancers for Robbins’s Fiddler on the Roof before it opened on Broadway. She was recognized for her outstanding contribution to American Jewish life with a medal by the American Tercentenary Committee.

Joyce Mollov (née Dorfman; 1925-1989), one of Lapson’s dancers, worked with her at the Jewish Education Committee. Mollov, who also performed with the Delakova-Berk company, received a master’s degree in dance education from Columbia University, was an adjunct lecturer at Queens College, directed the Jewish Dance Ensemble from 1967 to 1978, and coordinated the Jewish Dance Network for the Congress on Alternatives in Jewish Education. Since 1990 an annual program on Jewish dance has been held in her memory at Queens College.

Margalit Oved, (b. 1934, Aden) was part of the Magic Carpet airlift to Israel in 1949 and became one of Inbal Dance Theatre’s leading dancers and muse to Inbal’s director Sara Levi-Tanai. She left Israel in 1965 for Los Angeles, where she had a long teaching career at UCLA; she also directed her own company from 1971 to 1993, was the subject of the Allegra Fuller Snyder film Gestures of Sands, and influenced her son Barak Marshall to become a successful choreographer. He often featured his mother or her voice such as in his work “1972.” Oved’s original Mothers of Israel, choreographed for Ze’eva Cohen, was seen throughout the U.S.

Naima Prevots (b. 1935) studied at the Neighborhood Playhouse with Natanya Neuman and at the New Dance Group and performed with Delakova and Berk. Prevots remembers the fervor of Jewish dance activities, especially Israeli folk dance performances which accompanied the establishment of Israel. Like many of her contemporaries, she was a dance specialist in Jewish camps, teaching Israeli folk dance, and a member of He-Haluz ha-Za’ir, dancing for the Jewish National Fund and in Israeli folk dance performances. She danced in Pola Nirenska’s company from 1963 to1967, directed undergraduate and graduate dance programs at American University from 1967 to 2003, and has received a Fulbright Scholarship and National Endowment for the Arts awards. Her writing includes a biographical feature on Jewish dancer Benjamin Zemach.

Esther Nelson (b. 1928), born to Russian immigrant Communist parents, grew up in New York’s cooperative workers’ housing. Nelson studied with Julia Levien, danced with Delakova and Berk, and became an authority on children’s dance classes and author of articles and books about young children.

Frances Alenikoff (1920-2012) was born to Russian Jewish immigrants Clement Jack Lipman, who worked in the clothing trade, and Ruth Alper Lipman. Her Russian-born mother arrived in America as a young child, and danced with Sarah Mildred Strauss, and in Busby Berkeley movies, eventually becoming a yoga teacher. Frances studied with Marie Marchowsky, who taught in the Martha Graham style and charged fifty cents a lesson, but her formal dance training began at Brooklyn College. She was one of few white women accepted into Katherine Dunham’s school, where she learned African and Haitian dance, drumming, and singing. She toured to and taught in Mexico and Israel. Her company, the Aviv Theater of Song and Dance, also toured black schools throughout the South and often appeared at the 92nd Street Y. Through the Jewish Lecture Bureau of the Jewish Community Center movement, accompanied by Peter Yarrow, she developed a touring dance program on Jewish themes. In the mid-1970s she founded the Frances Alenikoff Dance Theater, featuring multi-media and texts including Re-Memory. A documentary about her work, Shaping Things: A Choreographic Journal, won a Ciné International Award for best dance film of 1978.

JoAnne Tucker (b.1943) studied with Helen Tamiris, graduated from Juilliard, and earned her Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin. From 1978 until 2004 she directed and choreographed for her dance company, the Avodah Dance Ensemble, which has traveled extensively in the United States, especially to synagogues and Jewish community centers. She taught workshops on A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash through dance at Hebrew Union College in New York and has written on the subject, including a book Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah in Motion: Creating Dance Midrash

Additional Jewish Modern Dancers

Leah Harpaz (d. 2008) studied with Dvora Lapson and Alwin Nikolais at Henry Street and performed with Benjamin Zemach’s New York group and with Eve Gentry and Helen Tamiris. As a mature dancer, she specialized in teaching the elderly and conducted a highly acclaimed class at the 92nd Street Y, specializing in dance for stroke victims and sufferers from Parkinson’s Disease and other physical disorders. She was active in the Israel Dance Library Association.

Eva Desca Garnet Rosen (1914-2015) studied and performed with the Denishawn Company, Humphrey-Weidman Company, the New Dance Group, and at the 92nd Street Y. In addition, she performed on Broadway in the Ziegfeld Follies and with Sophie Maslow and Marjorie Mazia, accompanied by Woody Guthrie. She later collaborated with the Dance Department at UC Irvine, including with Donald McKayle, who remembered Desca as his first dance teacher and choreographed a role for her in Generations. Eva returned to college at the age of 50 and received a Masters in Gerontology from the University of Southern California, pioneering exercise for seniors.

Judy Dunn (née Goldsmith; 1933–1983) danced with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 1959 to 1963. In 1960 she assisted her then-husband, Robert Ellis Dunn, with a series of dance composition classes that helped lead to the dance movement called “post-modern.” She was one of the founding members and the stage manager at Judson Dance Theatre’s historic first production on July 6, 1962, continuing in that position for several concerts. Among her dances presented there were Index, The Other Side, and Natural History. Dunn later collaborated with jazz composer Bill Dixon; they also taught together at Sarah Lawrence College. She then moved to Bennington College, where she taught until her death.

Aileen Passloff (b. 1931), who began choreographing in the 1950s, joined Robert Dunn’s workshop, which evolved into the Judson Dance Theatre, performing her works, which included Boa Constrictor, April and December, and Tea at the Palaz of Hoon. She became a dance teacher at Bard College.

Dance Theater Workshop

By 1965, critical and audience attention focused on the performances at New York’s Dance Theater Workshop (DTW) as an important site for modern dance. Originally housed in the loft of Jeff Duncan (who had performed in the Y’s Merry-Go-Rounders under Berk and in Humphrey’s company), DTW developed as a cooperative venture with many contemporary artists, including Francis Alenikoff, Liz Keen, and Ze’eva Cohen. The aim of DTW was to develop a collective of artists sharing expenses, office work, publicity, and performances.

Liz Keen (b. 1935) graduated from Barnard College and performed in the companies of Helen Tamiris (dancing in Womansong, 1960), Paul Taylor (Insects and Heroes, Junction, Rebus, and Three Epitaphs), Katherine Litz, Mary Anthony, and Judy Dunn. She received a Master of Fine Arts degree at Sarah Lawrence under Bessie Schönberg and then became Schönberg’s protégée, teaching dance composition with her at Jacob’s Pillow and in the Juilliard School Dance Department; she also teaches at the Alvin Ailey School and Company. She formed her own company in 1970. Quilt (1971) and A Polite Entertainment for Ladies and Gentlemen (1975) were particular successes. Though most connected with Dance Theater Workshop, her work has had wide exposure beyond New York. She also staged Salome for opera companies in New York, London, and other cities.

Ze’eva Cohen (b. 1940) first trained with Gertrud Kraus in her European Expressionist-style modern dance classes in Tel Aviv. Through Kraus’s training, Cohen found potent expression during her formative years; her dramatic qualities and charismatic performance proved appealing to many choreographers. Cohen first performed with the Rena Gluck Dance Company, then the Israeli co-operative modern company Bamat Mahol and with Anna Sokolow’s Lyric Theater in Tel Aviv. When Sokolow returned to New York, Cohen followed and became a featured performer in her New York company, a memorable interpreter of Sokolow’s dances, especially in Rooms. Cohen presaged the phenomenon of solo shows by commissioning 23 choreographers to create 28 solos for her, performing them in European dance festivals, throughout the United States, and in Israel from 1971 to 1986. Her programs garnered her the cover portrait and feature in the March 1976 Dance Magazine. She graduated from the Juilliard-Fordham joint program and received her Masters of Fine Arts from New York University. In addition to her solo programs, she was an active member of Dance Theater Workshop before founding Ze’eva Cohen and Dancers in 1983. She choreographed Goat Dance and Rainwood, Walkman Variations, Swamps and Forest, Wilderness, Female Mythologies, Women and Veils, If Eve Had A Daughter/Mother Tongue-I Love You (to Yiddish song and Klezmer music), Jeptha’s Daughter, and Negotiations. Her solo shows in the 1970s and 1980s were seen throughout the United States; her group works were also staged for the Boston Ballet, the Alvin Ailey Repertory Dance Ensemble, the Kibbutz Dance Company, the Batsheva Dance Company, Tanz Projekt, Pennsylvania Dance Theatre, and Chicago Repertory Dance Ensemble. Cohen created and directed the dance studies at Princeton University from 1969 until 2009. A 2005 documentary film Ze’eva Cohen: Creating A Life in Dance, was selected for the Dance on Camera Film festival at Lincoln Center, New York, and for Dance Camera West at MOCA, Los Angeles.

Those who have not particularly identified as Jewish include Martha Clarke (b. 1944), known for her multidisciplinary approach especially in The Garden of Earthly Delights. In 1990 she was awarded a MacArthur “genius grant” and The Dance Magazine Award in 2013.

Yvonne Rainer (b. 1934) is the daughter of Jeanette Rainer, a Jewish immigrant from Warsaw who considered herself a radical and took the young Rainer to ballet and opera in San Francisco. She studied with Graham, Halprin, and Robert Dunn, creating her famous Trio A in 1966. She is considered an experimental dancer, choreographer, and filmmaker and her importance documented as one of the three featured in Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer in California and NY, 1955-1972.

Cora Cahan (b. 1940) trained with May O'Donnell at the High School of Performing Arts and with Norman Walker at Juilliard and continued to work with both throughout her career. She briefly danced with Pearl Lang and Helen Tamiris; joined the faculty of the Juilliard School; danced the lead in Walker's Meditation of Orpheus (1964) and other works; served on the dance faculty of University of Cincinnati; worked as an administrator and executive director of Eliot Feld Ballet, where she helped turn a half-empty building into the prosperous Lawrence A. Wien Center for Dance and Theater; and served as president of The New 42nd Street Inc., a non-profit arts organization.

Laura Foreman (1937–2001) danced in the Helen Tamiris company as a youngster. She graduated from the University of Wisconsin at Madison with a degree in dance and in 1969 started teaching at the New School for Social Research, where she was director of the dance department from 1969 to 1999. She also taught at the 92nd Street Y. Foreman married composer John Watts, with whom she founded and co-directed the Composers and Choreographers’ Theater at the New School. In the 1970s she created and choreographed works for the Foreman Dance Company. In addition to dancing, she was a painter, sculptor, and writer.

Laura Dean (b. 1945) graduated from the High School of Performing Arts in New York, performed in the company of Paul Taylor, began choreographing in 1967, and formed her own company (1971 until 1994), favoring the minimalist style, with repetitive movement and spinning, and frequently collaborated with musician Steve Reich. In 1980 she also choreographed for the Joffrey Ballet.

Risa Steinberg (b. 1949) trained at the High School of Performing Arts and studied at the Juilliard dance program from 1967 to 1971. She also studied with Jewish teachers including Gertrude Shurr, Pearl Lang, and Bertram Ross. She began her career with the José Limón Dance Company (as did many other Jewish dancers, such as Maxine Steinman, Robyn Cutler, and Susan Bernhardt), performing there from 1971 to 1982 and dancing in Limón’s works (including A Choreographic Offering, There Is a Time, and Missa Brevis) and in Doris Humphrey’s The Shakers. After she left the Limón company, she began her solo performances, inspired by her work with Annabelle Gamson. The Danspace Project produced her solo program, at St. Mark’s Church, New York City, in March 2001. She guests and teaches at the Juilliard Dance program.

Sara Rudner (b. 1944) was born to first-generation Russian Jewish immigrants who supported her dance studies only as an avocation, although her maternal grandfather had sung in opera. She studied with Sandra Gentner at Barnard College, the New Dance Group, and Connecticut College. She performed in the Pearl Lang Dance Company and for Twyla Tharp’s dance company for more than two decades, as Tharp’s muse and main performer in many works, including Eight Jelly Rolls and The Fugue. From 1976 to 1982 Rudner directed, choreographed, and performed for her award-winning Sara Rudner Performance Ensemble. She taught at many universities, including New York University School of Fine Arts and SUNY/Purchase, and was chair of the dance program at Sarah Lawrence College from 1999 to 2019.

Choreographers in New York with their own companies who have choreographed on Jewish themes include Carolyn Dorfman (her work Mayne Mentshn, or My People, is a full-length work celebrating her Eastern European Jewish heritage); Risa Jaroslow (who has created works on her experiences in Poland); Tamar Rogoff (whose performance piece and film The Ivye Project were based on the site in Ivye, Belarus, where 2500 were murdered); Sasha Spielvogel (directs Labyrinth Theatre, her Holocaust piece is Noor); and Sara Pearson (Lot’s Wife), who, in addition to choreographing and co-directing her company has been associate professor at the University of Maryland since 2009; Heidi Latsky (b. 1958), who performed in the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company (1987–1991), created solos including Recalling Jack (An Ode to My Grandfather), in which she used giant Phylacteriestefillin, and Kol Nidre for the Sound Dance Repertory Company. Andrea Miller (b. 1982), graduate of Juilliard, directs her Gallim company, trained in Gaga and performed in Israel’s Batsheva II; her repertory includes Pupil Suite to Israeli Balkan Beat Box band.

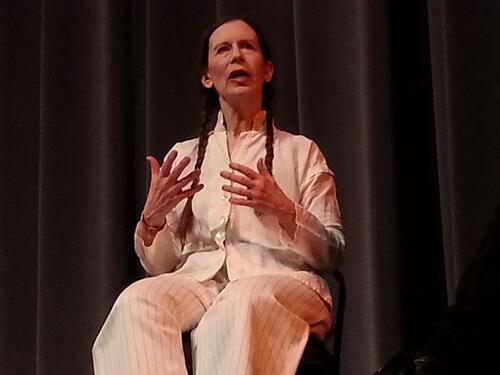

Meredith Monk at the Krannert Cernter for the Performing Arts in Urbana, Illinois, 2014.

Courtesy of Marc-Anthony Macon.

Meredith Monk, post-modern dancer, choreographer, and musician, studied with the Rom sisters in New York and danced Israeli folk dance with Fred Berk’s teen program, but her formal dance study was under Bessie Schönberg at Sarah Lawrence College, where she was also influenced by Judy Dunn. At Judson Church, she showed her 16-Millimeter Earrings and Duet with Cat’s Scream and Locomotive, incorporating voice and film. Monk has created unique performance pieces combining movement, music, singers, dancers, video, and film, beginning in 1968 with her company The House. Her major works, many with allusions to Judaism, include Quarry Education of the Girlchild, Ellis Island, Book of Days, Atlas: An Opera in Three Parts, and Mercy.

Ephrat Asherie’s grandfather, Zalman, was an avid dancer and came to Israel from Lithuania, but his parents and one of his brothers were killed in the Shoah. Zalman passed down his love for dancing to Asherie’s mother Nili, who in turn passed it down to her. Asherie, who was born in Israel, moved with her family to Italy and then New York. As a young person Asherie was a big hip hop fan, eventually becoming immersed in New York City’s underground dance community and the myriad of Black and Latinx vernacular dances that the community embodies, including breaking, hip hop and house. Bridging her Judaism with these styles can be seen in her choreography, especially her solo Papirosen, seen at the 92nd St Y’s Conney Conference of Jewish Arts in 2019. Her ensemble works, Riff This, Riff That and Odeon, collaborations with her jazz pianist brother, also cross cultures. Asherie was a 2016 Bessie Award Winner for Innovative Achievement and was awarded the prestigious National Dance Award. She graduated from Barnard College and received her MA from the University of Wisconsin.

Hadar Ahuvia (b. 1985), is an Israeli-American who trained with Lines in San Francisco/San Francisco Conservatory of Dance, graduated from Sarah Lawrence College dance department, and performed with Sara Rudner, Reggie Wilson/Fist & Heel Performance Group. Her signature piece “Everything You Have Is Yours?” reconsiders Zionism by looking at Israeli folk dance and song, premiered at the 14th St Y. In 2019, Dance Magazine featured Ahuvia in their “25 to Watch” series. Despite controversy, her solo was also shown at the main site of Israeli folk dance in the United States, the New York 92nd St Y, during the Conney Conference of Jewish Arts in 2019. A founding member of Jewish Voice for Peace Artists Council, she advocates a “flourishing Israel/Palestine.”

European Emigrés to the United States

Jewish modern dancers in Europe faced the Nazis’ deadly final solution; some who managed to escape to America included Katya Delakova, Claudia Vall, Pola Nirenska, Trudy Goth, Carola Trier, and Truda Kaschmann. Their dance style and experiences were so different that they received less notice than American-raised Jewish dancers. Nonetheless, they persevered in their profession.

Judith Berg (1912–1992), from a Polish Jewish family, trained in the modern expressionist style with Mary Wigman in Dresden but preferred to choreograph dances inspired by Jewish culture and Hasidic influence. She returned to Warsaw and was active in the Jewish Art Theater, choreographed for Ida Kaminska, and before the German invasion, ran one of the few accredited modern dance studios in Warsaw. She trained others interested in Jewish dance, such as Irena Prusicka and Rena Spatsenkop. Berg choreographed for the Yiddish Theater and for her own dance performances. Her most highly regarded work is her choreography for the 1937 Yiddish film of The Dybbuk. After the German invasion, she escaped to Soviet Russia, traveling and performing in Dzigan and Shumacher’s Yiddish troupe, which included actor-dancer Felix Fibich, who had been her pupil at the Yung Theatre. They married; after World War II, they were repatriated to Poland, where they created a Jewish school of dance for survivor children in Otwock; they then escaped the Communists for Paris, performing there and emigrating to the United States in 1950. The couple performed their duet recitals at Carnegie Hall and the Brooklyn Academy of Music and toured the United States, Canada, Israel, and South America. Judith Berg staged a Yiddish revival of Rebecca, the Rabbi’s Daughter at New York City Town Hall in November 1979. She became a specialist in teaching the elderly.

Katya Delakova (c. 1915–1991) fled the Nazis in 1939 and came to New York from her native Vienna, where she had worked with Gertrud Kraus. In 1941 she was reunited with another Kraus performer, Fred Berk, whom she later married. Together they formed the Delakova-Berk duo, which toured university campuses, Jewish community centers, and other venues from 1941 to 1950. They established the Jewish Dance Guild and the Jewish Dance Repertory Group and taught both at the 92nd Street Y and the Jewish Theological Seminary. They also performed in displaced persons camps in Europe in 1948 and in Israel in 1949. After she and Berk divorced, Delakova married Moshe Budmor, with whom she developed collaborative movement and music workshops, teaching both internationally and in the United States.

Trudy Goth (1913-1975) studied with Harald Kreutzberg and performed with Angiola Sartorio (1903-1995) in Italy. In 1940 Goth became Sartorio’s assistant and director of her school in Florence. Goth escaped to the United States, where she appeared with the Kurt Jooss dancer Henry Schwarze at Jacob’s Pillow. She founded Choreographer’s Workshop in 1946 at the 92nd Street Y, which produced performances in New York, and wrote about dance in publications such as Dance Magazine. Sartorio also escaped and taught in California.

Hannah Kroner (c. 1920-2015), a dancer with the Jewish Kulturbund in Germany under the Nazis, performed in operas such as Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin in November 1937 in Berlin. Though the circumstances were pitiful, at its peak in 1936, before most of the deportations, the Kulturbund employed nearly 2000 Jewish artists, who were allowed to perform only for Jewish audiences in special concerts. Kroner succeeded in emigrating to the United States with her family in November 1939. She ran her Hannah Kroner School of Dance in Bayside, New York, for more than 50 years.

Ruth (née Sklarz) Clark Lert (1915–1997) grew up in Berlin, where she received a diploma in dance despite her mother’s objections and performed in cabaret with Kurt Goetz before immigrating to the United States in 1936, where she taught for Steffi Nossen’s school in Westchester. She taught for Eugene Loring’s American School of Dance and became a recognized dance photographer, working in Los Angeles from 1956 to 1971. Her impressive collection was donated to the Dance Library and Archives at the University of California at Irvine.

Pola Nirenska (1910–1992) grew up in Poland in a middle-class Jewish family opposed to her interest in dance. Secretly she studied ballet. Nirenska won a Polish government scholarship to study further dance, including with Rosalia Chladek in Austria. She then went to Dresden, Germany, to study modern in 1928 with Mary Wigman, graduating from the Wigman school. From 1932 to 1933 she toured the United States and Germany in Wigman’s company. However, Wigman, a Hitler supporter, dismissed Nirenska and the other Jewish dancers in 1933. In 1935 she won first prize for choreography in Vienna’s International Dance Congress, which enabled her to tour Europe briefly as a solo dancer; she was also engaged by the Opera in Florence until Mussolini’s persecution forced her out. She fled to London, where she collaborated with Kurt Jooss and Sigurd Leeder. In 1949, she emigrated to New York where she studied with American modern dancers including Doris Humphrey and José Limón and began teaching dance arts in Carnegie Hall and at Adelphi College. She moved to Washington, D.C., founded the Pola Nirenska Dance Company in 1956, and in 1960 opened her own studio; she also co-founded The Performing Arts Guild, an association of modern dance companies in the Washington, D.C. area. Among her most prominent students were Liz Lerman [link to new entry on Liz Lerman] and Rima Faber, who was responsible for staging Nirenska’s work, including The Holocaust Tetralogy. While Nirenska was fortunate to escape the Nazis, she never escaped severe depression. The Pola Nirenska Award for Outstanding Contribution to Dance has been presented since 1994, funded by her late husband, Dr. Jan Karski. A second award in her memory, the Jan Karski and Pola Nirenska Prize, is a $5,000 stipend awarded annually by YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

Hedi (née Politzer) Pope (b. 1920) was encouraged by her parents Maria Berger and Oscar Politzer to study the arts and trained with the Vienna Opera soloist Hedy Pfundmayr, and with Grete Wiesenthal. In Vienna, she danced at the Burgtheatre and appeared in the film Silhouette in 1936. She escaped to the United States in 1939 and performed in the Broadway cabaret revue From Vienna, sponsored by Irving Berlin and George Kaufmann in appreciation of European refugees. In 1947 Pope opened her own dance studio in the Washington, D.C. area, which she ran for 35 years. She also founded the professional company, CODA (Contemporary Dancers of Alexandria).

Miriam Rochlin (1920-2012) was raised in Berlin and studied with Jutta Klamt until the Nazi period, immigrating to the United States in 1940. She worked with Benjamin Zemach from 1948 to 1967 as a dancer, assistant director, and production manager. In addition to teaching for the Bureau of Jewish Education in Los Angeles, she produced the documentary The Art of Benjamin Zemach in 1967.

Carola Strauss Trier, (1913-2000) daughter of Alice Rosenberg and Eduard Strauss, the important German Jewish philosopher and teacher, was born in Frankfurt and died in New York. She trained with Rudolf von Laban and with Kurt Jooss at the Folkwang Schule in Essen. She created solo shows and moved to Paris, dancing in vaudeville until she was interned in the Gurs transit camp, from which she escaped, reaching the United States in 1942. She worked with Joseph Pilates and opened the first independent Pilates studio, becoming a major Pilates teacher, healing countless dancers for 50 years.

Claudia Vall (b. Zagreb 1910, d. Los Angeles 2008) studied at Hellerau with Dalcroze, at the Vienna Academy of Music and Dance, and performed in the Gertrud Kraus Company in Vienna and in Italy with Angiola Sartorio’s company. Vall came to the United States in 1940 via Cuba, where she danced for more than a year with fellow Kraus veteran Fred Berk. In 1941 they performed at Hanya Holm’s summer festival in Colorado and at other venues. Berk went to New York, while Vall settled in Los Angeles, continuing ballet with Michel Panaieff, teaching children’s dance classes, and choreographing a long running children’s dance show for KTLA-TV.

Beyond New York

Many dancers have thrived outside New York, creating schools, companies, and repertoire, sometimes on Jewish themes. Hermene (1902–1986) and Josephine (1908–c. 2000) Schwarz were the daughters of Hanna (Lindeman) Schwarz, a sculptor, and Joseph Schwarz, a haberdashery owner. They studied ballet and modern dance with notable teachers in Chicago, New York, and Europe but made their mark in their hometown of Dayton, Ohio, where they founded the Schwarz School of Dance (to be inclusive, their lessons cost ten cents). Their Experimental Group for Young Dancers became the Dayton Theatre Dance Group in 1941 and in 1958 the Dayton Civic Ballet, America’s second-oldest regional ballet company. By 1972 the company performed at Jacob’s Pillow and at the Delacorte Theater in NYC’s Central Park.

Fannie Aronson (1903–1991) was important in the Detroit area. She studied at the Bennington summer school of dance and at the Dalcroze School in New York. After a brief period with the New Dance Group, she returned to Detroit, where she taught in the public schools and became a founding member of the Michigan Dance Council. She also taught and formed the first performing company at the Jewish Community Center, lectured, and wrote about dance.

Harriet Berg (b. 1924) has had a long career in the Detroit area. She studied dance at Wayne State University and in New York and taught at the Jewish Community Center of Metro Detroit, as well as at Marygrove College. She directed three companies, including the Festival Dancers and the Renaissance Dance Company, both in residence at the Jewish Community Center, and Madame Cadillac Dance Theater, specializing in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century dance. The latter company toured France, and in 1993 Berg received an award from the French government for promoting French-American relations.

Saida Gerrard (1913-2005), from Toronto, moved to New York in the 1930s, where she trained and performed with Hanya Holm. In 1945, she joined the Charles Weidman taught at the Humphrey-Weidman school from 1950 to 1953, and then moved to Los Angeles, teaching at the University of Southern California, UCLA, the Idyllwild Arts Festival, Los Angeles City College, and the University of Judaism, as well as performing and lecturing on Hebraic dance and modern dance with Jewish themes at Los Angeles Jewish temples. She directed her company from 1953 to 1960, performing with the Long Beach Symphony, the Idyllwild Arts Festival, at USC, UCLA, and the University of Judaism, under the management of Columbia Artists. She also choreographed for the Los Angeles Civic Grand Opera and staged works by Bertolt Brecht at the Mark Taper Forum and her own Golem at the Gindi Auditorium.

Bella Lewitzky (2016-2004) was born to Russian Jewish immigrants in a utopian community in the Mojave Desert. As an adolescent she moved with her father to Los Angeles, first studying and then performing with Lester Horton in his company for fourteen years. With Horton she choreographed Warsaw Ghetto and her only other Jewish-themed piece, Heritage. In 1947 she created the Dance Theater of Los Angeles with Horton and her composer husband, Newell Reynolds. From 1966 to 1995, she directed her own company, considered one of the main dance institutions in California. Her school was also very successful, and she taught at the Idyllwild School of Music and the Arts, directing the dance program. As a teacher, Lewitzky produced many professional performers, including Fanchon Shur.

Susan Salk (b. 1953) studied expressive modern under Sartorio and Horton style with Lewitzky, becoming assistant to the artist and executive directors of Lewitzky Dance Co. after graduation from UCLA. She was founding member of LA Ferne Ackerman’s Big Flood Co., studied Pilates with Ron Fletcher, and opened her Pilates Palm Springs in 2000.

Fanchon Shur danced in Los Angeles and after marrying musician Bonia Shur, settled in Cincinnati. She and her husband created works together, some on Jewish themes, including Tallit, which has toured extensively throughout the United States.

Anna Halprin (b. 1920) studied dance with Graham, Holm, and Humphrey-Weidman in New York, completed her formal education with a BA from the University of Wisconsin dance department, and moved to San Francisco in 1945. In 1955 she founded the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop, an avant-garde performance company which brought some of its radical performances to New York in the late 1960s. Halprin’s major choreographic work began in 1959. Considered an innovator, she used dance in rituals and participatory public dance events and as a process for social change and health. Her teaching methods gained national attention for incorporating cityscapes, landscapes, non-dancers, tasks, and dance maps turning into performance. In 1978 she co-founded the Tamalpa Institute with her landscape architect husband Lawrence Halprin; she received a Guggenheim Fellowship, several choreographic fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and, in 1980, the American Dance Guild Award for outstanding contributions in dance. She created dances with Jewish themes occasionally, including Kaddosh, commissioned by Temple Beth Shalom in 1960, and Grandfather Dance from “Memories from My Closet,” set to klezmer music, made into a dance film. Her most noteworthy work deals with healing and global concerns embodying the Jewish concept of Tikkun Olam, or fixing the world. In September 1995 her Planetary Dance: A Prayer for Peace was presented in Berlin to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. A prominent gallery exhibit seen in California and at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, with accompanying book, Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955-1972, placed Halprin as one of America’s major mid-century modern dance creators.

Gloria Newman (1927–1992) was an influential choreographer and dynamic teacher in New York and then Los Angeles and Orange counties from the 1960s to the 1980s. Studying or working with Graham, Horst, Humphrey, Weidman, and Cunningham, she also taught at Cornell University and New York’s High School of Performing Arts before moving to California in 1954. She formed the Gloria Newman Dance Theater in 1961 and influenced a generation of diverse Southern California college dance teachers. She choreographed 50 works and was the recipient of five National Endowment for the Arts grants, including one to stage Anna Sokolow’s Rooms.

Ruth Zaporah (b. 1936) was the daughter of Russian American Jews Ethel Himmelfarb (whose father, Hyman Himmelfarb, was a Yiddish poet) and Henry Glick. She studied at the studios of Graham and Nikolais in New York, then with Elizabeth Waters in New Mexico. Zaporah developed her theater/movement technique, Action Theater, teaching it in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and on tour in Israel, China, Europe, and throughout the United States. The Traveling Jewish Theater Company of Los Angeles commissioned her work Seduction. She also organized the Jewish Folk Dance Council and directed the Jewish Community Association modern dance ensemble.

Simone Forti (b. 1938 in Florence) was born to Italian Jewish parents Milke and Mario Forti, escaping the Nazis with them to Los Angeles. Forti studied at Reed College and worked in San Francisco with Anna Halprin from 1955 to 1959, performing in Halprin’s Dancers Workshop; she then moved to New York and as a post-modern dancer worked in Robert Dunn’s classes and began developing her Dance Constructions in 1960, which were purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in 2015 for its permanent collection. In the 1970s she returned to Italy, choreographing and participating in Festivals. She has taught at Cal Arts, at the School of Visual Arts in New York, and at the UCLA Department of World Dance. She was featured in the gallery exhibition Radical Bodies; Anna Halprin, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955-1972.

Esther Geoffrey, a Holm student in Colorado, danced on Broadway in 1943–1944 in Early to Bed and in summer stock operettas at Carnegie Hall. She made her career as a teacher in Colorado Springs, for 36 years teaching modern dance, jazz, and children’s creative dance at Colorado College.

Carol Teten née Davis (b. 1939), graduated in dance from Sarah Lawrence College and received her M.A. from University of California, Los Angeles. In 1977 she created “Dance Through Time,” which featured professional dancers performing social dances of western culture from the fifteenth century to the present, with extensive United States tours. Though based in San Francisco, Teten has researched archives in Europe and America to build her company repertoire. She also produced film documentaries of social dances from the 1400s through the 1990s.

Judith Brin Ingber [link to new entry on Judith Brin Ingber] (b. 1945) studied ballet with Lorand Andahazy in Minnesota, then modern dance at Sarah Lawrence College under Bessie Schönberg; she also studied with Fred Berk at the 92nd Street Y, later writing his authorized biography. She performed briefly with Anne Wilson Wangh and Meredith Monk. In Israel, from 1972 to 1977 she choreographed and taught for the Batsheva-Bat Dor Dance Society and was assistant to Sara Levi-Tanai, director of the Inbal Dance Theatre. From 1979 to 2008 she taught on the dance faculty at the University of Minnesota. In 1988 she co-founded and choreographed for Voices of Sepharad, touring in the U.S., Canada, and Europe. Her articles on Jewish dance have appeared in the International Encyclopedia of Dance, Dance Magazine, Dance Perspectives, and Israel Dance Annual, which she co-founded with Giora Manor, and Mahol Akhshav (Dance Today).

Margaret Jenkins (b. 1942) first became known as a performer in Twyla Tharp’s original company and then as an expert in staging Merce Cunningham’s works for other companies. She trained at the Juilliard School and taught for the Cunningham studio from 1964-1970, ran her own studio in New York, and then she returned to San Francisco. In 1973, she founded the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, choreographing over 60 works with extensive foreign travel focusing often on cross-cultural themes, including with the Amir Kolben Company of Jerusalem. Her work Breathe Normally includes themes of Jewish heritage and the Holocaust.

Liz Lerman (b. 1947) studied with Florence West, Pola Nirenska, and Miriam Rosen at the University of Maryland. Lerman founded the Liz Lerman Dance Exchange in 1976, her multi-generational, multi-racial dance company, for which she created many works, including The Hallelujah Project, Shehechianu, and The Good Jew? She has received many awards, including the first annual Pola Nirenska Award, grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a MacArthur Genius Grant in 2002. She collaborates with synagogues throughout the US, introducing a program at Temple Micah in Washington, D.C., and developing the national program she named Moving Jewish Communities. She relocated to Tucson and is Arizona State University’s first Professor at the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts. In 2018 she co-directed the international conference at ASU called “Jews and Jewishness in the Dance World” with Naomi Jackson.

Karen Goodman (b. 1947) is a Los Angeles choreographer, dancer, teacher, and Jewish dance researcher. She earned her Master of Fine Arts from Wayne State University, danced with Gloria Newman and post-modern master Rudy Perez in New York and Los Angeles, and received a 1990 NEA Choreographer’s Fellowship for her choreography. She opened her dance studio in Los Angeles and also made films and produced/directed the Yiddish dance documentary Come Let Us Dance (2002). She researches and lectures about Jewish choreographers including Nathan Vizonsky, often presenting papers at the Conney Conference on Jewish Arts, Univ of Wisconsin.

Beth Corning (b. 1954) studied with Ernestine Stodelle, Vera Blaine, and earned her MFA at The Ohio State University dance department. She ran her own company, Corning Dances and Co., in Stockholm, Sweden, from 1982 to 1986, then worked in New York City and Minneapolis from 1993 to 2003 (where she created three full-length performances on Jewish themes called The Human Trilogy: Night of Questions, Painted Windows, and Echoes in the Ghetto). From 2003 to 2010 she directed Dance Alloy Theater in Pittsburgh and then launched Corningworks, a vehicle for Glue Factory Projects for international dancers over 40 including The Waiting Room in 2018 about Jewish death rituals.

Heidi Duckler of Los Angeles has a 25-year-old site-specific dance company, working in courtrooms, gas stations, and famous hotels, among many other sites. Her 1998 work, “Laundromatinee,” was named an American Masterpiece by the National Endowment for the Arts. She has created several Jewish or Bible-related pieces, including her 2005 All the World’s a Narrow Bridge, based on Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav’s teaching.

Diane Elliot (b. 1950) created her contemporary dance touring company, which for 25 years was primarily based in Minneapolis. She became certified in Body-Mind Centering, then an ordained rabbi, known for her workshops focusing on embodying the spirit. She presents spiritual movement workshops at synagogues, conferences, and through ALEPH, Alliance for Jewish Renewal. At the 2018 “Jews and Jewishness in the Dance World” international conference at Arizona State University, she created a full Shabbat service in dance for conference participants.

Shira Greenberg (b. 1972) trained at the Minnesota Dance Theatre in ballet and modern, has directed Keshet Dance and Center for the Arts in Albuquerque since 1996. She choreographs for the Keshet company including on the Holocaust, sponsors incubator programs for dancers from other communities, and directs a comprehensive school for all ages. She also brings in dance artists including Israeli dancers to teach master classes and choreograph.

Sara Pearson (b. 1949) began training and performing with Hanya Holm’s protégée Nancy Hauser in Minnesota and danced in the Murray Louis dance troupe from 1973 to 1976, later creating her company with Patrik Widrig, touring extensively in India, Europe, and the United States. In addition to choreographing and co-directing her company, since 2009 she is associate professor at the University of Maryland’s dance department. In 2002 she created Lot’s Wife for the PearsonWidrig Theater’s Joyce Theater season; it was seen again in 2018 at the “Jews and Jewishness in the Dance World” international conference.

Nina Haft directs Haft and Company, in Oakland, CA. and teaches at California State University East Bay. In the 1990s and 2000s she choreographed works with Jewish themes, including Minyan and Mit a Bing! Mit a Boom! A Klezmer Dance, though recently she has been inspired by the natural world.

Lillian Rose Barbeito and Tina Finkelman Bekett created Body Traffic Dance Company in 2007 in Los Angeles and often feature Israeli choreographers and Jewish themed work.

Abrahami, Naomi. “Did Hamlet Have a Jewish Conscience? Pearl Lang’s Dances Celebrate a People’s Survival and Humanism.” The Forward. September 28, 2001.

Bennahum, Ninotchka, Wendy Perron and Bruce Robertson. Radical Bodies; Anna Halprin, Simone Forti, and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955-1972. Santa Barbara: University of California Press, 2017.

Berg, Judith. Choreographer. Restored film of 1937 The Dybbuk. National Center for Jewish Film. ncjf@jewishfilm.edu

Berger, Miriam Roskin. “Dance as Therapy: A Jewish Perspective”. Mahol Akhshav [Dance Today #36]. September, 2019. 79-83. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.israeldance-diaries.co.il/en/.

Berk, Fred. The Jewish Dance. New York: Exposition Press, 1960.

Bianu, R. Sonja Gaze: The Barefooted Dancer. Neue Welt, Vienna: August/September 2002.

Burke, Siobhan. “Her Roots Are Tangled in Folk Dance and Israel.” New York Times,

Feb. 6, 2018. Accessed Aug. 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/06/arts/dance/hadar-ahuvia-everything-you-have-is-yours-israeli-folk-dance.html.

Chochem, Corinne. Jewish Holiday Dances. New York: Behrman House, 1948.

Cohen-Stratyner, Barbara Naomi. Biographical Dictionary of Dance. New York: Schirmer, 1982.

Draegin, Lois. “Jewish Dance Vaults Centuries and Styles.” New York Times. September 14, 1986.

Dunn, Judith. “My Work and Judson’s.” Ballet Review. 1(6), 1967. 22-26.

Faber, Rima. “Ghosts of the Past: The Creation of Pola Nirenska’s Holocaust Tetralogy.” Judith Brin Ingber and Ruth Eshel, eds. Mahol Akhshav [Dance Today #36], Autumn 2019. 34-38. Accessed June 10, 2020. https://www.israeldance-diaries.co.il/en/.

Fibich. Judith Berg. “Jewish Choreographer, Obituary”. New York Times. August 29, 1992.