Esther Brandeau

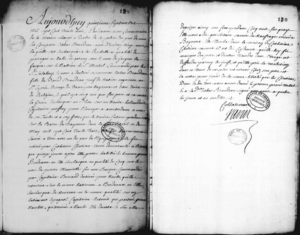

Record of the interrogation of Esther Brandeau, a young Jewish woman who "embarked at La Rochelle, as a passenger, in a boy's clothes, under the name of Jacques Lafargue, on the ship the Saint-Michel," captained by Sieur Sallaberry. Signed Varin. September 15, 1738. Via the Library and Archives of Canada.

Esther Brandeau was born in southwestern France around 1718, descended from exiles of the Inquisition in Iberia. A record of interrogation accounts for Brandeau’s passing as Christian and male across France for five years before setting sail as Jacques La Fargue from La Rochelle, France. Doubly outed at or en route to Québec, Brandeau | La Fargue was ultimately deported from New France, purportedly for refusing to convert to Christianity. Stories of female-to-male passing and Jewish to Christian passing among Sephardic Jewish people in Iberia and its diaspora were not uncommon in early modern Europe. The story spread, almost exclusively in Canada. Its power lies at the intersection of what and how we (do not) know, and why and when we tell.

Introduction

It is almost impossible to know who Esther Brandeau | Jacques La Fargue really was and how they experienced their eighteenth-century travels across gender and religion, over land and sea, across names and identities. Like many on the margins of centuries past, they come to us only through observers’ third-person accounts: an interrogation record scribed by colonial officials in Québec, speculation by a bureaucrat back in France, passing reference in a nun’s letter to a friend.

Born in around 1718, Esther Brandeau | Jacques La Fargue hailed from the Jewish quarter across the river from Bayonne, France. This was one of several communities in the French Basque region established by Jewish and Converso (New Christian) exiles of the Inquisitions in Portugal and Spain. Brandeau | La Fargue purportedly spent five years travelling France as Christian and male before boarding a Québec-bound ship at La Rochelle in 1738. Sometime during that crossing or through interrogation upon arrival, the Christian Jacques La Fargue was doubly outed as Brandeau, Jewish and female. We don’t know by whom nor how s|he was outed, nor whether Brandeau was actually a practicing Jew or a Conversa (convert to Christianity). Open Jewish practice was permitted in France only beginning in 1723, when Brandeau was around five years old. Earlier, exiles either practiced secretly, had lost traditions through forced assimilation, or had embraced Christian life.

Brandeau | La Fargue arrived in Québec in the territories of the Abenaki, Atikamekw, Wabanaki and Wendat Indigenous peoples, whose unceded lands were being divvied up as colonization efforts were in full swing. At the time, non-Catholics were barred from New France, a colony that would be lost to the British a few decades later. Only with the British did the first openly Jewish settlers arrive in what we now call Canada. Brandeau | La Fargue has been claimed by some as the first Jew, or the first Jewish woman, in Canada.

The bureaucratic response to Brandeau | La Fargue’s arrival was house arrest, failed attempts at conversion, and deportation. Official documentation ends with the decision to send Brandeau back to France purportedly for refusing to convert, but surely claiming the domain of men through passing didn’t earn Brandeau any favor either. A barter between the Crown and a the outfitter of a ship was struck to ensure what was perhaps one of Canada’s earliest deportations. In exchange for returning Brandeau to France, a captain was exempted from a portion of the number of indentured laborers he would ordinarily have been required to bring back on his next voyage. Whether Brandeau boarded that France-bound ship is unknown.

Cultural and scholarly uptake

This story has mostly remained within Canadian Jewish histories and histories of New France (where it has been consistently noted since the late nineteenth century) and among Canadian cultural producers—historians, journalists, writers, artists—particularly in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Little published research exists about Brandeau | La Fargue beyond reiterations of the archival documents. The case has garnered attention at key moments when questions of identity, belonging, equality, and difference have been at the forefront of public debate, underscoring the role that normative gender and religious difference have long played in sculpting belonging in Canada as a settler society.

Esther Brandeau | Jacques La Fargue has been featured in three novels, an art installation, film scripts, a short story, a case study in anthologies about remarkable women for young learners, and on stage. In a collection of comedic essays about Canadian oddballs, radio personality Bill Richardson posits Brandeau as one of Canada’s foundational eccentrics. In Shelley Tepperman’s documentary about Quebec City Jewry, Brandeau is a time-traveling secret narrator passing as a twenty-first-century non-Jewish student. All these works have been produced in Canada.

Never-produced film adaptations go back decades. Three creative works do deploy video to animate the story: Wendy Oberlander’s conceptual art installation Translating Esther; Tepperman’s documentary Les juifs de Québec : une histoire à raconter; and (this author) Heather Hermant’s performance works. Sharon McKay’s historical fiction for young readers entitled Esther has arguably done the most to circulate the story, first and foremost to anglophone Canada; it was not translated to French until twelve years after its English publication. Quebec author Pierre Lasry’s deeply researched historical fiction Une juive en Nouvelle-France (translated as Esther: A Jewish Odyssey) preceded McKay’s and has been recognized primarily within Jewish circles. A fantastical novel by poet Susan Glickman is entitled The Tale-Teller (translated as Les aventures étranges et surprenantes d’Esther Brandeau, moussaillon).

Engagements with Brandeau | La Fargue’s story have primarily foregrounded themes of gender equality, racism and discrimination, religious freedom, and interculturality. The story has been used to further claims—not without critique—of longstanding Jewish presence in Canada. Without suggesting Brandeau | La Fargue was queer, the story has been taken up by a handful of queer artists and scholars, given the resonance of gender passing with LGBTQ+ experiences and histories. I inaugurated the dual naming convention “Esther Brandeau | Jacques La Fargue” and fluctuate between the use of she, he, s|he and they as pronouns. While Jacques La Fargue’s outing catapulted this story into the historical record, Brandeau also adopted the identity Pierre Mausiette (sometimes read as Alansiette). These naming and pronoun choices have been adopted by others, although the use of “they” has also drawn criticism as ahistorical.

The story has most often been framed as extraordinary, but gender crossing from female to male was not uncommon in early modern Europe, often catalyzed by poverty. Jewish to Christian passing was (forcefully) common in Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic histories. Although some cases from the period involve a woman passing in order to follow a male love to sea or into the army, such a claim in this case would be speculative. While we have no insight into the sexual life of Brandeau | La Fargue, nor how they experienced what we would today call the “genders” of the day, the record suggests that Brandeau | La Fargue lived various masculinities, possibly for considerable lengths of time, enabled by the interplay between local, regional, and colonial transatlantic circuits. Within these circuits, this sustained intersection of passings—across gender, religion, possibly social standing and age, certainly language, and of course, geography—makes this story highly significant. It is rare to find accounts from the period of “multicrossers,” people who passed in multiple ways concurrently.

What does the written evidence tell (and not tell) us?

As is often the case with outed passers, the evidence comes primarily from conditions of acute and gendered power imbalances. In this case, a rule-breaking migrant faces the punitive authorities of state, church, and family: senior colonial administrators with the power to determine Brandeau | La Fargue’s fate, religious authorities housing and feeding while pressing for conversion, and officials in Bayonne with the capacity to locate and inform family.

The central piece of evidence is a brief third-person retroactive account in the annals of New France, which documents one of two known interrogations. Correspondence between bureaucrats on either side of the Atlantic adds to this evidence. No first-person account exists. Only one account by a woman exists, written by Sister Marie-Andrée Duplessis de Sainte-Hélène, who writes not in her official capacity as a nun and Mother Superior of the Hospitallers convent at which Brandeau was housed for a time, but rather in a letter to a friend. Her account challenges claims made by Brandeau | La Fargue’s interrogator, Intendant of New France Gilles Hocquart.

According to the interrogation record, the story began on a Dutch boat in Bayonne. Brandeau was being sent to an aunt and a brother in Amsterdam, center of eighteenth-century Converso/re-judaized life. Brandeau’s father is identified as David Brandeau, a Bayonne Jew and merchant. A mother is not identified. French officials suggested that Esther Brandeau may have been David Brandeau’s illegitimate child, and that he may have had several other children at home.

The boat was said to have been lost on the Bayonne sandbar, with Brandeau rescued alongside one of the crew. After a short stay with a Christian widow in nearby coastal Biarritz, Brandeau set off as male, travelling across a sizeable swath of France. Brandeau | La Fargue worked as a cook on a boat before moving overland and working in various assistant positions: for a tailor, a baker, a religious order, and finally for a retired soldier. A brief stay in a French prison was apparently the result of an arrest for thievery made in error. Many of these places officially claimed no Jewish communities at the time. It is not clear whether they travelled on the Québec-bound ship as a sailor or as a passenger.

Once in Québec, Brandeau was housed first at the convent, later at private houses, and finally either with the prison warden’s family or in the prison proper. Throughout, extensive but failed efforts were made to secure Brandeau’s religious conversion.

Interrogators asked why s|he had “disguised her sex.” In a two-part answer, the first of which may or may not have compelled the second, Brandeau | La Fargue answered by addressing disguising their Jewishness. First, Brandeau claimed to have been forced to eat pork and other non-kosher meats while housed with the widow post-shipwreck. We could read into this that shame for the violation of Jewish dietary restrictions made it impossible to return home. This required remaining Christian, which in turn required remaining male. Second, they said they had decided that taking advantage of the same freedoms as Christians was more attractive an option than returning home. This suggests that passing as male and Christian opened Brandeau to a world of freedoms s|he had not had access to as a Jewish woman. It’s not easy to disentangle the Jewish experience from the female experience here. According to Duplessis de Sainte-Hélène, however, Brandeau had set off because she was not as well liked as one of her sisters, suggesting yet another motivation.

Many interpreters have taken the interrogation record to mean Brandeau | La Fargue was torn between religious loyalty and desire for a life in the so-called New World. These interpreters have assumed Brandeau | La Fargue’s Jewish conviction, but refusal to convert could just as easily have been motivated by a dislike of the colony and a desire to return to France. Intendant Hocquart gives mixed messages, seeming to say, “she can stay if she converts!” and “should she be allowed to leave if she converts?” The evidence suggests a bureaucratic desire to keep her (as her) in New France, at a time when marriageable Christian women were in demand.

In addition to the alternative account of Brandeau’s motivation, Duplessis de Saint-Hélène writes that s|he had arrived a sailor, had been suspected on board of being female, had refused to admit it, and only later told the Intendant that she was female. Intendant Hocquart, on the other hand, claims Brandeau was found to be female by chance during the crossing. A queer perspective would highlight the discrepancy between voluntary outing and the violence of involuntary outing. The account of testimony further states that she was sent by her parents to Amsterdam, while Duplessis de Saint-Hélène claims she left of her own accord. No word on how Jewishness was revealed.

The interrogation record accounts for only a fraction of the time between departure on that Amsterdam-bound boat in 1733 and arrival in Quebec in 1738. Details in the interrogation record have generally been taken at face value. However, names of people Brandeau | La Fargue purportedly worked for and which have been assumed to be last names of men are in fact more likely first names, in one case the first name of a woman and in another possibly the name of a monastery. What has always been read as the catalyzing shipwreck was more likely a non-catastrophic sandbar incident, then common in Bayonne. The interrogation record could well be evidence of strategic documenting and/or of strategic testimony.

Uncertain endings

Bureaucratic correspondence begins in 1738 and ends in 1740. Thereafter Brandeau | La Fargue disappears from colonial records, but not from possibilities opened by speculative threads in local and regional French archives. A tombstone unearthed in recent years in the Bayonne Jewish cemetery is of interest. On it, Esther Pereira Brandon is noted as having died in 1744. Neither birth date nor parents are listed on the tombstone, and no corresponding birth record exists. Brandon along with Brandam—both derived from the Portuguese Brandão—are the two source names used in Bayonne for what was recorded as Brandeau in New France. If Esther Brandeau | Jacques La Fargue was indeed twenty years old when outed in Québec, then this tombstone would mean death in Bayonne at age twenty-six. There are a few other possible Esther Brandon/Brandams to choose from, but genealogical information, along with details in the interrogation record and research in petitions for financial support for the Jewish community’s orphaned and poor, suggest that if anything, Esther Pereira Brandon would be the more likely, if indeed Brandeau | La Fargue ever returned to France.

As with so many aspects of this case, maybe is the operative word. Whether and to what extent our protagonist engineered their journey and/or its possibly open ending, we don’t know. Esther Brandeau | Jacques La Fargue ultimately escapes the capture of a conclusive record, securing their disruptive potential more than three centuries after their birth.

Selected primary sources

“Lettres de Marie-Andrée Duplessis de Sainte-Hélène, Supérieure Des Hospitalières de L’Hotel-Dieu de Québec.” Nova Francia, 1926, 234.

"Procès-verbal de l'interrogatoire d'Esther Brandeau, jeune juive qui s'est embarquée à La Rochelle, en qualité de passager, en habit de garçon, sous le nom…’" September 15, 1738, Archives nationales d’outre-mer (France), Fonds des Colonies, Série C11A, Correspondence générale, Canada, (FR ANOM COL C11 A 70), ff.129-130. This and other documents are available in digital scan online at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca

Selected creative works

Glickman, Susan. Les aventures étranges et surprenantes d’Esther Brandeau: roman. Montréal, Québec: Boréal, 2014.

Glickman, Susan. The Tale-Teller: A Novel. Markham, Ontario: Cormorant Books, 2012.

Hermant, Heather. ribcage: this wide passage (dir. Diane Roberts, music Jaron Freeman-Fox), theater performance, Montréal Arts Interculturels, Montréal, Québec, October 28, 2010; Firehall Arts Centre, Vancouver, British Columbia, March 3, 2015.

Hermant, Heather. thorax : une cage en éclats (dir. Diane Roberts, music Jaron Freeman-Fox, trans. Nadine Desrochers), AKI Studio Theatre, Toronto, Ontario, 2013. See trailer here: https://vimeo.com/73170354.

Hughes, Susan, and Willow Dawson. No Girls Allowed: Tales of Daring Women Dressed as Men for Love, Freedom and Adventure. Toronto, Ont.; Tonawanda, NY: Kids Can Press, 2008.

Lasry, Pierre. Esther: A Jewish Odyssey. Montréal: Midbar Editions, 2002.

Lasry, Pierre. Une Juive en Nouvelle-France. Montréal: Les Editions du CIDIHCA, 2000.

McKay, Sharon E. Esther, trans. Diane Ménard. Paris: l’École des loisirs, 2018.

McKay, Sharon E. Esther. Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2004.

Oberlander, Wendy. “Translating Esther.” Exhibition, Koffler Gallery, Toronto, May 20, 2003.

Richardson, Bill. Scorned & Beloved: Dead of Winter Meetings with Canadian Eccentrics. Toronto: Knopf Canada, 1997.

Tepperman, Shelley. Les Juifs Au Québec : Une Histoire à Raconter, video, Montréal: Canal D and Productions Vélocité, 2008. See subtitled excerpt, The Jews of Quebec City: An Untold Story here: https://vimeo.com/24878879

Anctil, Pierre, and Simon Jacobs, eds. Les Juifs de Québec: Quatre Cents Ans d’histoire. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2015.

Bodian, Miriam. Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation: Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Choquette, Leslie. Frenchmen Into Peasants: Modernity and Tradition in the Peopling of French Canada. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Dekker, Rudolf M., and Lotte van de Pol. The Tradition of Female Transvestism in Early Modern Europe. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Hermant, Heather. “Esther Brandeau / Jacques La Fargue: A Multicrosser in the Canadian Cultural Archive.” In The Sephardic Atlantic: Colonial Histories and Postcolonial Perspectives, edited by Sina Rauschenbach and Jonathan Schorsch, 299–331. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Hermant, Heather. “Esther Brandeau / Jacques La Fargue: Performing a Reading of an Eighteenth Century Multicrosser.” Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University, 2017.

Nahon, Gérard. “The Portuguese Nation of Saint-Esprit-Les-Bayonne: The American Dimension.” In The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450 to 1800, edited by Paolo Bernardini and Norman Fiering, 255–67. New York: Berghahn Books, 2001.

Pierret, Philipe. "Inventaire du cimetière isralélite de Saint-Esprit-lez-Bayonne," Unpublished, 2018.

Sienna, Noam. A Rainbow Thread: An Anthology of Queer Jewish Texts from the First Century to 1969. Philadelphia: Print-O-Craft, 2019.

Steinberg, Sylvie. La Confusion Des Sexes: Le Travestissement de La Renaissance à La Révolution. Paris: Fayard, 2001.

Velasco, Sherry M. The Lieutenant Nun: Transgenderism, Lesbian Desire & Catalina de Erauso. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000.

Wheelwright, Julie. Amazons and Military Maids: Women Who Dressed as Men in the Pursuit of Life, Liberty, and Happiness. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1989.