Bettina Aptheker

Bettina Aptheker is an American feminist, writer, educator, and political activist. Born to a famous Jewish Marxist historian father and activist, she built her own personal and professional identity as a Jewish lesbian academic. After spending many years trying to please her parents by marrying a Communist man and building a life as a scholar-activist in her father’s footsteps, Aptheker stunned her family and community by announcing she was a lesbian, divorcing her husband, and marrying her life partner, Kate Miller, with whom she raised their three children. Aptheker went on to co-found the Women’s Studies program at UC Santa Cruz, then redesign the program as the Feminist Studies department.

Personal Life

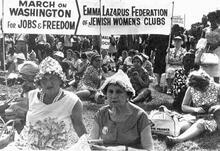

Bettina Aptheker was born on September 2, 1944, in North Carolina as the first and only child of politically engaged parents Fay Philippa Aptheker and Herbert Aptheker, both Jewish. Her mother was a union organizer; she was also a pianist and during Bettina’s childhood sang in the Jewish People’s Philharmonic Chorus, which gave concerts at Carnegie Hall. Her father Herbert was a Marxist historian whose famous research into African American history fueled Bettina’s early teaching career in African American Studies. When Bettina was a child, the family moved to Brooklyn, where she had the opportunity to learn from W.E.B. Du Bois, her father’s lifelong friend.

Herbert’s Marxist organizing was deeply influenced by his Judaism, and many of his contemporaries in the movement were Jewish as well. Aptheker later recalled watching her father grieve the deaths of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on June 19, 1953. For her, this was a moment of recognizing her Jewishness, a Jewishness she shared with the Rosenbergs (Intimate Politics, 23). She was afraid for months that the FBI would come take her and her family away, as they did the Rosenbergs.

Aptheker writes that she felt expected to follow in her father’s footsteps and become a Marxist organizer. She writes of her experiences at summer camp at Camp Wyandot with other children of progressive leaders, also Marxists (Intimate Politics, 24). During her years earning her Bachelors degree at University of California-Berkeley, she took a leading role in the Free Speech Movement on campus in 1964. Aptheker briefly retired from her blazing organizer days to marry fellow Berkeley student and campus Communist activist Jack Kurzweil in August 1965; the couple had two children.

Racial Justice Advocacy

Growing up in a household dedicated to racial justice permanently impacted Aptheker’s social consciousness. Collaborating with Angela Davis, a famous professor, activist, community organizer, and Black Panther, has been one of the key elements of Aptheker’s life and professional career. The two first met as children growing up in Brooklyn together. They reunited in 1969 after Davis was fired from her position as Lecturer in UCLA’s Philosophy Department because of her affiliation with the Communist Party. Davis’ membership was made public in a letter to the editor of UCLA’s student newspaper, the Daily Bruin, by a student who was a paid informant for the FBI (Intimate Politics, 200).

On October 13, 1970, Davis was arrested in New York on a fugitive warrant from California after a man named Jonathan Jackson used guns registered to her to interrupt a court hearing, ultimately taking the district attorney and several jurors hostage and leading to several deaths. Aptheker came to her old friend’s aid by lending her experience as a community organizer to the team’s legal strategy of public education, in order to generate social pressure to guarantee a fair outcome (Intimate Politics, 226). With the support of her husband, Jack, and a rotating schedule of caregivers for her young son, Aptheker canvassed, made phone calls, prepared pamphlets, and supported her friend’s campaign for freedom. These actions paid off, and with the help of attorney Margaret Burnham, on June 2, 1972, Davis received a judgment of “not guilty” (Intimate Politics, 257).

Aptheker’s first book, If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance (1971), was written collaboratively with Davis during Davis’ incarceration, as the two held regular visits and worked to keep one another’s hope alive. These conversations were key to shaping Aptheker’s future feminist ideology. Davis’ commitment to feminist theory, particularly early feminist theory by scholars such as Kate Millett and Shulamith Firestone, introduced Aptheker to these texts in a way she had never considered them before, which ultimately became key to her pedagogy (Intimate Politics, 248). If they Come in the Morning had a first printing of 400,000. After Davis was exonerated, Aptheker wrote The Morning Breaks (1976), her own account of the trial and her heartbreak over what happened to her friend.

Aptheker was inspired to return to university following Davis’s trial and the publication of her books. She felt that the Communist Party had interfered with the publication of her second book and begun to push her out following the conclusion of Angela Davis’ trial. This experience left her seeking an identity elsehwere and pushed her to seek opportunities beyond the freelance writing career she had cultivated up to that point. In 1976, she entered a Masters program in Communications at San Jose State University, where her husband Jack taught. She was offered a part-time graduate student teaching position, which became a full-time faculty position while she was writing her thesis. Her Masters thesis, like so much of her later research, focused on African American women’s studies. The first course she taught for the university was called “History of Black Women.” Teaching this course was her first exposure to Women’s Studies as a discipline (Intimate Politics, 276). Although initially unsure about the validity of Women’s Studies as its own unique field due to hostility she had encountered in Marxist circles and fear of leaving her own Marxist loyalties behind forever, as well as due to buried fears about her burgeoning lesbianism (Intimate Politics, 277), Aptheker quickly found an intellectual home within the Women’s Studies department at San Jose State. In 1977, she developed and taught a new course on “Sex and Power.”

By 1978, Aptheker had filed for divorce due to her budding lesbian identity and the couple’s mutual unhappiness. Fearing she would be unable to support her family without a further graduate degree, Aptheker soon became a graduate student in the University of California-Santa Cruz’s History of Consciousness PhD program. Within a year, she became the first official hire in UC-Santa Cruz’s brand-new Women’s Studies department. In October 1979, she re-encountered her life partner, Kate Miller, at a Holly Near concert. The two had first met when Kate was Bettina’s student at San Jose State years earlier. By June of 1980, they were living together, with their two cats, Aptheker’s two children, and Miller’s one child.

Research Interests and Scholarship

Aptheker’s research has focused on the histories and lives of marginalized women. She began her career by prioritizing research into the lives of African American women. This fascination began in childhood, when she watched the most famous Black scholars of her parents’ day move in progressive New York intellectual and artistic circles and she felt the women were on the periphery (Intimate Politics, 17). When she chose this topic for her Master’s thesis, minimal scholarship existed. Aptheker joined a small group of committed progressive women who shared their resources, along with their passionate commitment to the foregrounding the study of women who had so long been overlooked by traditional academia.

Aptheker’s focus on giving voice to the voiceless has never faltered. Her third book, Women’s Legacy: Essays on Race, Sex, and Class in American History (1982), which emerged from her dissertation research, focuses on the history of African American women and links class exploitation with sexist oppression. Since then, Aptheker has regularly been asked to write commentaries and forewards for the work of key African American women scholars. Her review essay of At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape and Resistance by Danielle L. McGuire (20210), entitled “Freedom’s Architects: Feminists Re-vision the History of the Modern Civil Rights Movement,” was published in the Women’s Review of Books in 2011.She has also been a key supporter of the rights of Jews of Color. For example, she reviewed The Color of Jews: Radical Politics and Radical Diasporism by Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz for the Women’s Review of Books in 2008.

After work on her memoir, Intimate Politics, which was published in 2006, Aptheker turned to another deeply personal topic: queer people in the Communist party, or, to cite her title, Communists in Closets (2023). This book focuses on the many members of the Communist Party during the period of 1938-1991 when the official Communist Parrty policy labeled all LGBT people as “degenerates.” Aptheker did extensive research into the many members of the Party who did high-profile work on the frontlines of the most important issues of the time while being very, very queer in their private lives.

Family Abuse History

In 2003, in her eulogy at a memorial service for her father, Aptheker for the first time spoke to a childhood of abuse, but she also praised her father for expressing remorse and anguish when she confronted him about it. Three years later, in 2006, her memoir included a number of private details about her family history. These details, especially the statement that her father had sexually abused her, caused a strong public reaction that impacted the response to her book.

In her memoir, Aptheker asserts that her memories of the abuse were hidden even from her own conscious mind for a period, though repressing them left her seriously depressed and even suicidal for much of her life (32). In the 1990s, when she was in her 50s and felt safe enough in Santa Cruz, and after her mother had passed away and could not be hurt by the revelation, the memories began to surface. Shortly after her mother’s death in 1999, she writes, she had a conversation with her father about the abuse after he asked her “Did I ever hurt you as a child?” She states that he acknowledged what he did and was able to somewhat understand the pain he cased, though whether due to his advanced age or to the mechanisms of psychological denial, he later seemed to have forgotten the conversation. Aptheker’s partner, Kate Miller, who was present for this challenging conversation, corroborated her account, and Aptheker’s daughter, Jenny Kurzweil, recalled when her mother was first full of memories of the abuse and sank into a depression (Phelps).

Aptheker’s memoir left members of the Marxist community in an uproar. Some historians and Marxist activists who thought highly of Herbert Aptheker publicly questioned Bettina’s memories. Others questioned the very possibility of repressed or recovered memories, citing “false memory syndrome” in which targeted therapy can manipulate memories (Phelps).

Many other readers, however, defended Aptheker. Some, like African American Studies scholar John Bracey, Jr., praised her greatness of spirit in keeping the matter quiet until both her parents were dead and could not be harmed by her decision to disclose the abuse. Others pointed to the widespread prevalence of child sexual abuse; women supporters, especially, invoked their own experiences of abuse (Phelps).

Aptheker continues to speak publicly about her memories of her experiences of abuse. Her syllabi discuss child sexual abuse, and when she tells her students her own story, her 500-seat lecture hall is always filled to overflowing.

Feminist Studies at UCSC

In the spring of 1978, only months after her divorce, Aptheker was hired by the University of California-Santa Cruz to teach the Black Women’s History class she had been teaching at San Jose. She embraced the nonhierarchical nature of the hiring process and of the department. Her experience on campus encouraged her to apply to the PhD program in the History of Consciousness department at UCSC. From there, she was hired to teach as the first full-time faculty member for the budding Women’s Studies department, which had been founded by students and faculty in 1975. She partnered with dedicated faculty, staff, and students to build the department.

Aptheker’s first Women’s Studies class at UCSC had 35 students. As of the early 2020s, the keystone Introduction course has 500 students or more, with students sitting in the aisles, on the floor in front, sometimes crowded into doorways. Over Aptheker’s 30 years of teaching, thousands of women learned from her to speak the language of their own bodies and minds for the first time, reclaiming their lives, voices, and destinies because of her influence.

Under Aptheker’s patient guidance, jobs at the UCSC Women’s Studies department became among the most sought-after in the field. In 2004, it was renamed the Feminist Studies department, in order to embrace a social change-oriented focus, integrating classes on racial justice and international collaboration and movement-building. The department is Aptheker’s legacy, and it is going strong.

After Aptheker stopped teaching Introduction to Feminisms in 2009, she developed a new introductory course, Feminism and Social Justice. In 2019, she partnered with UCSC’s mass online learning platform to create a four-pillar version of the course for the online platform Coursera, called “Feminism and Social Justice,” which by 2023 had been taken by over 113,000 students from every continent.

The Bettina Aptheker Award for Research on Sexual, Gendered, and Racial Violence Endowment was created in Spring 2018, the year of Aptheker’s official retirement. The award has been granted to four UC-Santa Cruz students as of 2024. The 2023 award winner, Millie Montoya, is a Feminist Studies and Sociology double major who works with the CARE resource enter on campus to support survivors of violence.

Leaving a Legacy

Aptheker officially retired from UCSC in 2018 but taught for three more years. Her final class was a graduate seminar that ended when Covid emerged in 2020. Aptheker continued to mentor graduate students and faculty, officially hooding her final graduate student in 2023. She taught over 16,000 Feminist Studies students (UCSC NewsCenter).

Judaism remains a key part of Aptheker’s life. She was a founding member of the Jewish Studies Program at UC Santa Cruz and remains a valued member of Temple Beth El, a Reform synagogue in Aptos, CA. She has made special appearances at several Pride Shabbat events to offer lectures about Jewish LGBT+ history.

While her Jewish heritage remains a key part of Aptheker’s life, her spiritual practice has turned more towards Buddhism ever since her partner convinced her to attend a teaching of the Dalai Lama in 1989 (Intimate Politics, 463). Meditation initially came as a challenge to Aptheker, who was not used to staying still, but in his presence she experienced a deep compassion that she found transformative. Aptheker dedicated herself to meditation and to a study of the teaching of interconnection, of the Buddhist practice of “emptiness”— that all things arise in relationship to one another, and no thing exists on its own. These teachings have informed Aptheker’s ongoing peace activism and resistance to, for example, the US war in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In 2009, when Aptheker offered her last Introduction to Feminist Studies course, all of the lights in the building suddenly went out in the middle of the lecture. The rest of the class was completed with students on their cell phones, reading the texts by what shared light they could evoke. Then, supernaturally, as soon as the class was finished, the lights spontaneously returned.

In 2023, Aptheker was honored by the alumnae association of UC-Santa Cruz with the Ethos Award for her commitment to social justice and to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Postscript

According to the national child sexual abuse prevention organization Darkness to Light, approximately one in ten children experiences child sexual abuse. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists estimates the number at between 12 and 40%, in its Committee Opinion, released August 2011 and reaffirmed in 2022, entitled “Adult Manifestations of Childhood Sexual Abuse.” The Vera Institute of Justice, a national organization fighting to end mass incarceration, notes that children with disabilities are three times more likely to be victimized, and children with intellectual or mental health disabilities are even more vulnerable. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists report points to a host of long-lasting or even lifelong problems caused by child sexual abuse, including PTSD, depression, and physical health problems.

“Adult Manifestations of Childhood Sexual Abuse.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, 2011, reaffirmed 2022; https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2011/08/adult-manifestations-of-childhood-sexual-abuse

Aptheker, Bettina. “The FSM: A Historical Narrative.” From the Free Speech Movement Archives. Published originally in FSM: The Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, by the W.E.B. Du Bois Clubs of America, 1965; https://fsm-a.org/stacks/b_aptheker.html

Aptheker, Bettina. The Coursera Blog. June 9, 2020; https://blog.coursera.org/prof-aptheker-on-activism-suffrage-intersectional-feminism/

Aptheker, Bettina. Intimate Politics: How I Grew Up Red, Fought for Free Speech, and Became a Feminist Rebel. Seal Press: Emeryville, CA, 2006.

Phelps, Christopher. “Father of History: Bettina Aptheker’s recent memoir has incited fierce debate over her father’s legacy.” The Nation, October 18, 2007.

Townsend, Catherine and A.A. Rheingold. Estimating a Child Sexual Abuse Prevalence Rate for Practitioners: A Review of Child Sexual Abuse Prevalence Studies. Charleston, SC: Darkness to Light, August 2013; https://www.d2l.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/PREVALENCE-RATE-WHITE-PA….

Walker, Tara Fatemi. “Bettina Aptheker Honored for Lifetime Commitment to Social Justice.” UC Santa Cruz NewsCenter. November 21, 2023; https://news.ucsc.edu/2023/11/bettina-aptheker-alumni-awards.html.