Friha Ben Adiba

Friḥa Ben Adiba was a Hebrew poet and highly learned in rabbinical writings. She is known to us by two of her Hebrew piyyutim, ie. liturgical poems, bearing her acrostic. Friḥa was born and grew in Morocco. Around 1750, she arrived in Tunis with her father, Rabbi Abraham Ben Adiba, who also wrote long Judeo-Arabic poems, looking for a safe place. A few years later she died as a martyr in a pogrom conducted by Ottoman janissaries from Algiers. To memorialize his learned daughter, her father transformed her bedroom in a mikveh (ritual bath) and her library into a synagogue, known as Slat Friḥa. Until its destruction in 1937, the synagogue was visited not only by faithful who came to pray but also by women who considered Friḥa a saintly figure and asked her protection and healing.

Introduction

Among the hundreds of Hebrew poets who wrote thousands of poems in North Africa between the ninth and the twentieth centuries, Friḥa Ben Adiba is the only known female poet. Friḥa, the daughter of Rabbi Abraham Ben Adiba, was born in Morocco in the second quarter of the eighteenth century. She was martyred in the pogroms in Tunis in 1756, apparently in the third decade of her life. Only two of her Hebrew poems, one long (“Turn to us in mercy,” with the refrain “Hear my voice in the morning”) and one short (“Lift up my steps, o Lord, my savior”) have been uncovered. Rabbi David Katorza, the acting Chief Rabbi of Tunisian Jewry from 1936 to 1939, recounted in a letter to the secretary of the Tunisian government that Marius Fischer, a scholar who visited what was known as the Friḥa synagogue in 1863, found there nine of her Hebrew poems bearing her acrostic; he added that Friḥa “was a very beautiful girl, who had particularly great knowledge, rode horses and played music” (letter from Rabbi David Katorza, November 11, 1936). Unfortunately, despite intensive research, no additional information about Fischer or Friha has been discovered.

Friha’s poetic writing was exceptional in two ways. First, following the statement by Rabbi Eliezer, a sage of the Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah era, that “Anyone who teaches his daughter Torah teaches her rubbish” (Mishnah Sota, chapter III, mishnah 4), Jewish women in Morocco and elsewhere received little to no formal education in Hebrew from the early Middle Ages until the era of emancipation in Europe. Subsequently, Jewish women’s education depended on their communities’ openness to modernization; in Morocco, it was only in 1862, with the foundation of the first French school by the Jewish philanthropic society the Alliance Israélite Universelle, that girls’ education began in earnest. Like a few daughters of rabbis in Morocco and elsewhere, Friḥa enjoyed a solid individual education in rabbinics thanks to her father Abraham, who was a rabbi and a Judeo-Arabic poet.

Moreover, Friha’s authoritative rabbinic education permitted her not only to read and understand foundational Hebrew writings but even to create and compose liturgical Hebrew liturgical poempiyyutim, similar to those written by the Moroccan rabbis of her generation. She wrote in a rich biblical Hebrew and focused on an idyllic Jewish past before the destruction of the Second Temple and exile, the terrible present of suffering and persecutions in the Diaspora, and the messianic future that would repair these ills. However, unlike other rabbinic poets, Friḥa emphasized her personal feelings about the dramatic Jewish fate, rather than collective and communal feelings. According to an article published by the editor of the Judeo-Arabic newspaper Al-Yahudi of Tunis (see below), in addition to her poems, Friḥa also wrote rabbinical texts, which have not survived, and she had at her disposal a great rabbinic library.

Discovering a Liturgical Poem by Friḥa

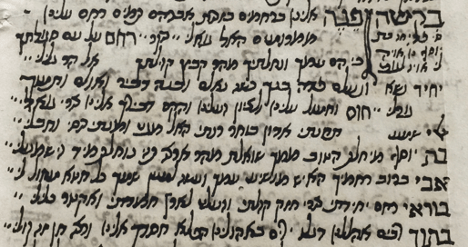

How were Friha’s identity as a poet and her long bakkasha (pl. bakkashot) “Turn to us in mercy (a liturgical poem of supplication and praise of God, recited before morning prayer) discovered? In December 1978, while I was in Strasbourg, France, to lecture on Moroccan Jewish poetry, a student from Meknes, Morocco, invited me to view his family’s rabbinic library, which included several manuscripts of Hebrew poetry. One of these manuscripts, dating from the nineteenth century, contained dozens of bakkashot written by Hebrew poets from medieval Spain and the Ottoman empire, as well as by Moroccan poets. One had the description: “Bakkasha with the acrostic Friḥa bat Yosef [Friḥa daughter of Joseph].” Friḥa, meaning a little joy in Moroccan Judeo-Arabic, is a common woman’s name in Moroccan Jewry, generally given to female babies born after the death of a brother or sister. The external acrostic Friḥa (פריחא) appears in the initial letters (emphasized by the copyist in bold) of the five first stanzas. The compound “bat Yosef” begins the sixth stanza. The author’s full name appears as an internal acrostic spread over the three last stanzas: “Abraham” as her father in the seventh stanza, “bar Yiṣḥaq” [son of Isaac] as her grandfather in the eighth stanza, and “bar Adiba” as the family name in the last stanza. The poet’s full name is thus Friḥa bat Abraham ben Yiṣḥaq ben Adiba. The surname “bat Yosef” that appears in the acrostic points not to her name but to her messianic beliefs, which are very clear in the poem, and refers to the Messiah descended from the Biblical figure Yosef, who should appear, according to the Midrash, before the Messiah descended from King David. Friha’s father is known for his Judeo-Arabic poems, the most famous of which is a long qasida (a narrative poem in the Moroccan tradition) about the suffering of Job and his recovery according to the biblical story, Midrashic commentaries, and some Arabic-Muslim details.

Friḥa’s Tragic Death and her Memorialization

Friḥa grew up in Morocco. She lived with her family, probably in the Jewish community of Oujda, nearby the frontier with Algeria, whose Jewish cemetery houses tombs bearing Friha’s first and family names. How did she arrive in Tunis, where she died? The November 26, 1936, issue of the Judeo-Arabic newspaper al-Yahudi, published in Tunis, included an article entitled “Tfakir Slat Friḥa” [the memory of Friḥa synagogue]. According to this article, the poet arrived in Tunis, probably via Tlemcen in northwestern Algeria, with her father and brother (according to Rabbi Katorza, with her father and mother) in the mid-eighteenth century, seeking refuge from the riots that were embittering the lives of Moroccan Jewry at the time. In 1756, however, the janissaries of the Ottoman Empire who were stationed in Algiers invaded Tunis and ran amok among its residents, both Jews and Muslims. Some members of the Jewish community found shelter in Tripoli, Libya, and returned when the fighting died down. Rabbi Abraham Ben Adiba left Tunis with his son but was unable to take Friḥa with them. After his return to Tunis, he did not find his daughter, but after conducting an intensive investigation into her disappearance, he learned that she died as a martyr. To memorialize his learned daughter’s name, he turned her bedroom into a ritual bath and the room where her library had been kept into a synagogue, with a Holy Ark in place of the bookshelves.

Friḥa's name became a saintly one on the lips of Tunisian Jewry. The building became a pilgrimage site for young Jewish women, who prayed that Friḥa's merit would protect them, alleviating their pains and healing their illnesses. Many legends became bound up with her name, with no relationship to the events that brought about the building of the synagogue. The memorial site was destroyed in 1937 to make way for extensive renovations that the city of Tunis had decided to carry out in the old Jewish quarter, but the Holy Ark was saved and transferred to a new synagogue. The 1936 newspaper article also included a second, shorter Hebrew poem, written by Friḥa.

Two Translated Poems by Friḥa

פנה אלינו ברחמים “Turn to us in Mercy”

Turn to us in Mercy

By Abraham’s virtue and merit,

Turn to us with compassion.

From on high have mercy upon us,

My Lord, and my redemption.

Hear my voice in the morning.

Have mercy on the people You’ve chosen,

For they are Your nation and share.

Hurry and gather Your congregation,

Upon the Galilean Mountain.

Hear my voice in the morning.

Alone, exalted and not to be seen,

Redeem Your son like a lamb gone dumb.

Then build a shrine and hall,

And resurrect my fortune.

Hear my voice in the morning.

Have pity upon us,

And bring us up toward Zion.

Establish Your shrine there for us,

My Rock and my Redemption.

Hear my voice in the morning./span>

Hear, my God, my supplication,

Choose, Lord, my song.

My shield, Lord, my portion,

My cup, my destination.

Hear my voice in the morning.

The daughter of Yosef longs,

Seeks goodness from You alone.

Soon her land will be given,

Restored from the Ishmaelites’ hand.

Hear my voice in the morning.

Father, in all Your compassion,

Let Your people’s savior be hastened.

And act for Your name alone,

Pardon all my transgression.

Hear my voice in the morning.

Pity my soul, my salvation,

Strengthen, my Rock, my congregation,

Carry me to the land of my yearning,

Where I’ll bring a perfect offering.

Hear my voice in the morning.

Among the many I’ll praise Him.

We will raise His banner over our tents.

Astonish me in Your compassion,

Desire my voice’s blessing.

Hear my voice in the morning.

פעמי הרימה, יה מצילי “Raise up my steps, O Lord, my savior”

Raise up my steps, O Lord, my savior,

Let me go to my land in good grace!

I’ve been pursued by an ignorant foe

Who thundered into my face.

Bring me anon to my Galilean Mount,

Send fury and wrath at their cry.

There show me Your light, let me don my crown.

Then will I say, now I can die. (Hebrew)

(Translated by Peter Cole, in The Defiant Muse: Hebrew Feminist Poems from Antiquity to the Present: A Bilingual Anthology, edited by Shirley Kaufman, Galit Hasan-Rokem, and Tamar S. Hess. New York: Feminist Press, 1999, 75–77.)

Bashan, Eliezer. Jewish Women of Valour in Morocco. Tel Aviv: Eretz and Ashkelon Academic College, 2003 [Hebrew]. See in particular chapter XIII: 125-143.

Chetrit, Joseph. "Friḥa bat Yosef, a Poetess who Wrote Hebrew poems in Morocco in the 18th Century.” Pecamim 4 (Winter 1980): 84-93 [Hebrew].

Chetrit, Joseph. "Friḥa bat Rabbi Abraham: A New Uncovering about the Moroccan Hebrew Poetess in 18th Century.” Pecamim 54 (1993): 126-130 [Hebrew].

Chetrit, Joseph. “The Piyyutim of Friha bat Yosef with a New Document about Her Life and Her Death.” Deḥak, Literary Review nº 1 (2011): 36-42 [Hebrew].

Chetrit, Joseph. “In Search of a Lost Poetess.” Segula nº 59 (November 2021): 30-37 (translated from Hebrew).

Primary sources

Hebrew Manuscript Chetrit of Piyutim from Meknes, 19th century (no pagination).

Al-Yahudi (Judeo-Arabic newspaper), Tunis, November 26, 1936, p. 1.

A letter of Rabbi David Katorza, acting Chief Rabbi of Tunisia, 1936-1939, to the secretary of Tunisian government, November 11, 1936, about the foundation of the Friḥa synagogue (collection of Dr. Claude Nataf, Paris).