What Do Jewish Ethics Say about Vaccination?

Living through a pandemic has increased interest in an esoteric field: biomedical ethics. Over the last year, we have found ourselves collectively swept up in the minutiae of efficacy trials, vaccination development, distribution timelines, and vaccine lines. In 2020, the possibility of mass vaccination seemed far off, but now, months into 2021, it’s no longer distant. People in my life are vaccinated now; I’m vaccinated. It happened, to quote John Green paraphrasing Hemingway—“slowly, then all at once.” Although, like many, I have opinions about the most effective and fair system of vaccination, my mental calculations about who deserved what at what time evolved to accommodate myself when my number got called. After I got jabbed, I worried about how to share that I had begun my vaccination process. Was I obliged to share it online so that people wouldn’t judge my (potential) future behaviors? Was it obnoxious to publicize this information when so many people were still struggling to make appointments? How much responsibility did I, as an individual, have for a rollout that was prioritizing those with the ability to refresh web pages all day, not those at highest risk for hospitalization?

I already spend more time than most thinking about ethics, mostly by osmosis: My partner, Max, is a moral philosopher and ethicist. We’ve been talking a lot about Jewish approaches to biomedical ethics, especially as vaccinations ramp up. We can turn to biomedical ethics and Jewish ethics to make sense of and assess people's behaviors during the pandemic—their adherence to safety guidelines and their choices about when to be vaccinated. Though the problematic, Islam-exclusionary phrase “Judeo-Christian values” suggests frequent overlap between Judaism and Christianity when it comes to morality and ethics, Jewish tradition is distinct and has its own set of principles with implications for decision-making during public health crises.

Chaya Greenberger, a lecturer in nursing at Jerusalem College of Technology who has published extensively in philosophy and ethics, writes in Nursing Ethics: “Essential values held sacred in the Jewish tradition are similar to those cherished by most religious and cultural groups. These include respect for sanctity and quality of life, and human dignity, honesty, equality, and social solidarity. Respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and distributive justice.” In practice, however, she notes that “these principles tend to clash with one another. The challenge becomes how to decide which principle reigns supreme in a given situation...Jewish bioethics reflects an eclectic approach to this challenge.”

What makes it eclectic? We are reliant on interpretations—both from rabbinical sources like the Talmud as well from our cultural heritage, personal experiences, sense of religious identity, and political compass. Greenberger explains, “Judaism is based upon a divinely ordained, but humanly interpreted ‘blueprint’ for a moral life in all realms…Jewish bioethics nests within this blueprint. The G-d-given Biblical scriptures along with their exegetic guidelines and a core of oral teachings, form the basis for a continuously growing corpus of Jewish philosophy and halacha.” In theory, all Judaic ethics stem from the words accepted to be either Divinely given or inspired. In practice, it’s really, really complicated.

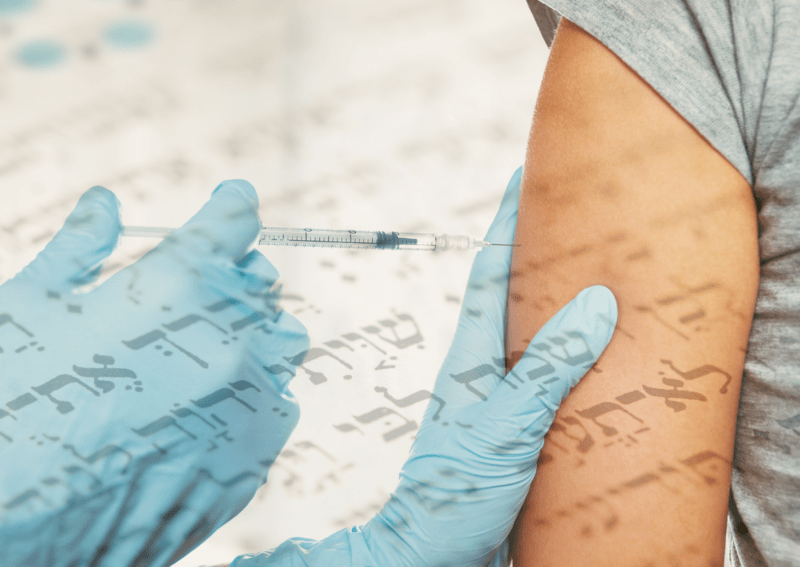

In the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, as we navigate vaccine access, vaccine hesitancy, and the invocation of the term ethics to mean something inherent and obvious—what can genuine Judaic approaches offer us? Greenberger sees immunization as an obligation among Jewish-identified people on the basis of common scripture, but also as a component of community responsibility. “A slow but steady trend to decline routine immunization has evolved over the past few decades, despite [the] pivotal role [of vaccination] in staving off life-threatening communicable diseases,” she writes in another article for journal Nursing Ethics detailing Jewish approaches to vaccination. “Judaism embraces evidence-based information regarding immunization safety and efficacy and holds the resulting professional guidelines to be religiously binding. From a Jewish perspective, government bodies need to weigh respect for individual autonomy to refrain from immunization against preserving public safety, such that waiving autonomy should be reserved for immediately life-threatening situations.”

The only country in the world to espouse an explicit relationship to halacha is, of course, Israel. The country has been lauded as leading the globe in vaccination efforts (obligation to those in territories it currently occupies excluded). Israel has not mandated COVID-19 vaccination, but has incentivized it heavily, promising a “two-tiered” system for those who forgo immunity through vaccination. Part of their successes are undoubtedly tied to their nationalized healthcare system—something the United States lacks, and desperately needs. In the United States, our healthcare system is a confusing web of public and privatized hospitals, some of which have the right to refuse procedures based on religious opposition (which happens with alarming frequency when it comes to reproductive care). For a country so preoccupied with imagined “Judeo-Christian” ethics, the US is deeply uninterested in establishing the kind of infrastructure that would allow health justice to become a reality, rather than a patchwork system of haves and have-nots.

Greenberger, writing about Judaic ethics more broadly, summarizes the central and driving tenets of Jewish values thusly: “The obligation to preserve the dignity of the human being, created in G-d’s image; The prohibition against actively taking a life (save in self-defense); The obligation to take responsibility for preserving one’s own life, health and well-being...The prohibition against standing by idly in the face of a threat to life or quality of life of a fellow human being; The obligation to provide for the basic human needs of the socially and economically under-privileged.” These are ideas that are present in nearly all systems of faith, and are undoubtedly agreeable to the most secular among us. This ongoing health crisis presents us with an opportunity to make good on the values that we have claimed all along. In other words—according to Jewish ethics, you should absolutely get vaccinated as soon as it is possible for you to do so. And we should absolutely overhaul our healthcare system.

Ultimately, I’ve made peace with my luck in vaccination by paying it forward. As an individual, I can’t overhaul our healthcare system to make it more just—but I can do everything within my power to make sure as many people in my community as possible get vaccinated. I can help friends, family, and neighbors register for vaccine appointments, drive them to their location, and become a soup fairy for those struggling after their second dose. And I can continue to agitate and organize on behalf of a single-payer healthcare system—one driven by people, not profits.