Through the Window: Interview with Author Ameya Narvankar

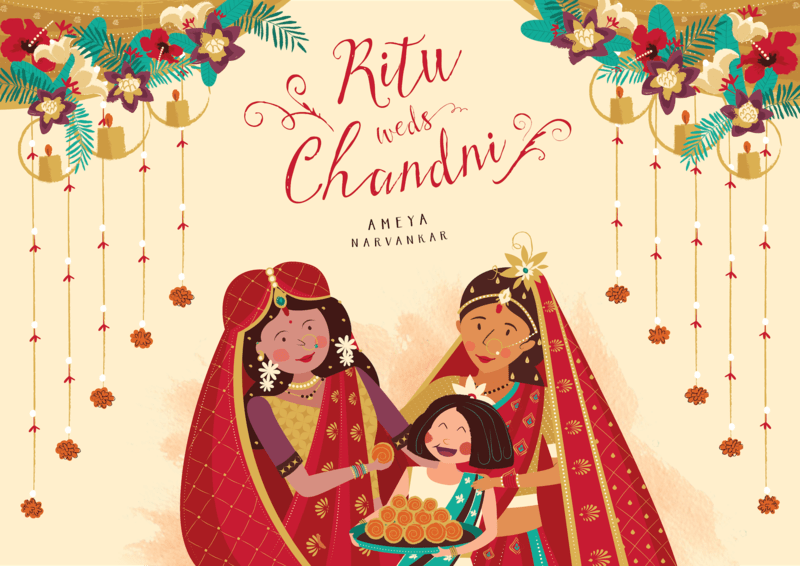

As part of the Association of Jewish Libraries’ program Through the Window: A Diversity Exchange, which pairs Jewish and non-Jewish organizations to swap blog posts, JWA is partnering with Yali Books, an independent publisher of South Asian stories. We’ve teamed up to bring readers an interview with Ameya Narvankar, the author-illustrator of Ritu Weds Chandni, a children’s book about six-year-old Ayesha, whose favorite cousin Ritu is marrying her girlfriend Chandni. Narvankar is a multidisciplinary designer, visual artist, and bookmaker from India. An alumnus of IIT-Bombay, Ameya believes in the power of design to bring about change, which he hopes to achieve through his foray into children’s literature. He loves, in no particular order, cats, bearded men, and Beyoncé (who doesn’t?). Ritu Weds Chandni (Winter 2020) is available for pre-order through Yali Books.

Ritu Weds Chandni sets the story of a same-sex couple struggling to gain acceptance against the backdrop of an Indian wedding. Why did you write this story?

This book emerged from my thesis project titled “The Visibility & Representation of LGBTQ People in Indian Society.” I looked at how the queer community is portrayed in popular media and art, particularly those catering to younger audiences. I found mainstream media in India had shied away from accurately representing the community, instead choosing caricatures that are often cruel and downright homophobic. As a gay man who grew up on a staple of Bollywood films, I found these depictions appalling. I wrote and illustrated Ritu Weds Chandni in an attempt to create positive LGBTQ role models, which I hope will add to the larger conversation around representation.

Why did you choose to write it for young readers using the format of a picture book? Will children understand the complex issues underlying the narrative?

We are conditioned from a young age to conform to heteronormative gender roles and, by extension, sexual identity. We feel this need to “otherize” ideas we don't understand, and soon enough, homophobia raises its ugly head. I chose to reach out to young readers to break this cycle. The protagonist of the book, six-year-old Ayesha observes, asks questions and tries to make sense of the resistance and stigma faced by her cousin. I am hoping young readers of the book will do the same.

What would you say to detractors who believe a depiction of a same-sex couple in story is not suitable for children? What would you say to those who claim such relationships are not “part of our Indian culture”?

Same-sex relationships are a reality and a visible part of our society today. Children observe these individuals and have questions. Do parents want their children to glean possibly harmful information from scattered sources? Instead, I would like for them to talk to their children after reading or watching positive and uplifting stories depicting LGBTQ+ families. Homosexuality is often dismissed in India as a Western concept. In reality, the law (now abolished) that criminalized homosexuality was instated during the British Raj. Queerness was very much a part of pre-colonial India. Hindu mythology and folk stories have varied queer themes. These stories reflect an Indian society that was more tolerant, even embracing, of those who are different.

What is the significance of a baraat in Indian weddings? What is the role of the baraat in this story?

A baraat is a procession led by the groom on a horse and is one of the most recognizable symbols of a wedding in some parts of India. His family bands together; there is singing and dancing and merrymaking all around. In my story, the baraat stands in for a Pride parade. It is not just a celebration of the union of two women, but also a celebration of their identities by their friends and families. It also serves to upend gender stereotypes—it is customary for only the groom to have a baraat, but in Ritu Weds Chandni, both brides lead their processions to the wedding venue.

As a man, why did you choose female protagonists? What were some of the challenges in writing across gender?

I believe intersectionality is the backbone of every social movement. In patriarchal Indian families, queer women are doubly marginalized. By shining a spotlight on two women in this story, I hope the conversation around this book will be multifaceted and nuanced in its discussion of human rights. I chose to use the picture book format to show rather than tell because I couldn’t create multi-dimensional female characters solely in my writing. Instead, I played to my strengths as a visual communicator to represent the emotions of my characters through art, which adds depth to my words.

You live in India. What are some of the changes you have witnessed in the perception and treatment of LGBTQIA+ communities in recent times?

As of the year of publication, same-sex marriage will still not be legally recognized in India. Same-sex relationships have been decriminalized only as recently as 2018. With this archaic law now struck down, the visibility of the community has increased, and many have found the courage to come out to their loved ones. Pride parades take place in almost all major Indian cities now. Representation in popular media has improved. Bollywood films and television shows now feature queer protagonists. I feel this is a step in the right direction. However, the fight is far from over, and it is going to be an uphill battle to gain wider social acceptance in India.

What advice would you give families and educators who would like to use this book to start a conversation with children? What are some gentle questions to ask kids after they have read the book?

One of the reasons I wrote the book was to enable parents and educators to have those difficult and sometimes awkward conversations on this topic with children. With this introduction, I am hoping children will ask questions, and their caregivers will find resources to help them develop a deeper understanding. A good place to start the conversation would be—“Why do you think people in the story objected to two women getting married?” Or, “Do you think two women (or men) can get married?” I want them to realize that everyone has the right to lead their life with freedom, dignity, and love. The collective empathy of children and their families today can make a big difference in building a more inclusive society tomorrow.

This post is part of The Association of Jewish Libraries’ program Through the Window: A Diversity Exchange, which pairs Jewish and non-Jewish organizations to swap blog posts. This initiative is designed to fight antisemitism, racism, and other forms of bigotry through education and allyship.