My Many Moms Are My Matriarchs

"Lady Lilith" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1866. Via Wikipedia.

My moms love Mother’s Day. One of them always jokes about how it’s “the most important day of the year.” And I guess in our family, she’s right. As queerspawn and a child of divorce, I have three moms.

After my mom and stepmom got married a few years ago, we started going out all together for Mother's Day brunch. And by all of us, I mean my mom and stepmom, my stepmom's ex and her new partner, my stepbrother, my other mom, my brother, and I. It’s a lot of moms, I know.

I remember distracting others in elementary school every year on Father’s Day while they were using multi-colored sheets of paper to show their love for their dads—and on Mother’s Day, always asking for extra sheets of paper and rushing to make my second card.

Growing up, I encountered those who believed the toxic myths that children “need” a dad in order to thrive, but my own lived experiences invalidate and dispel those myths. Looking back, I see how growing up with strong, smart women as my role models affected me. They are my matriarchs, and being shaped by them has made me the person I am today.

Being raised in a matriarchal household has also led me to an inescapable realization: the history we learn in school is filled with societies run by men. So, I went searching for matriarchal leadership on a larger scale, and what I found is that, especially during this time of coronavirus chaos, studies show women leaders are doing, well, better at it. For example, Jacinda Ardern, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, has successfully flattened the curve in her country. In fact, so far, out of five million New Zealanders, there have only been twenty deaths.

And she’s not alone: Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen, Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg, and other women leaders have all succeeded at handling the pandemic better than their male counterparts. But why? I heard New York Times writer Amanda Taub say in a podcast interview that the “traditional idea of what a strong leader looks like...is very tied to masculinity.” I wanted to learn more, and found an article that Taub wrote explaining that, although the traditional idea of leadership is tied to masculinity, that model falls apart in a pandemic. In fact, she points out that “having a female leader is one signal that people of diverse backgrounds—and thus, hopefully, diverse perspectives on how to combat crises—are able to win seats at that table.” Traditional (and toxic) masculine traits include not wanting to acknowledge problems or ask for help with them. According to Taub, a common trait among women leaders is to seek out a diversity of people and opinions in order to energize their work. This is a trait that’s necessary in a leader, especially now. I find it fascinating, then, that female leadership is often portrayed negatively.

The story of Lilith is a great example. In Jewish mythology, Lilith was the first woman and was created from the same clay as Adam. She refused to play a subservient role to Adam, grew wings, and flew away. Her significant mentions in Judaism are as a demon, and, overall, she is referred to as Adam’s demonic first wife. Because Lilith refused to submit to Adam, she wasn’t portrayed as an independent woman or a leader; instead, she was an angry demon.

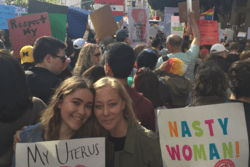

This reaction to Lilith is not unlike the reactions that standing up to sexism can bring about today; after all, it's misogyny in our world that categorizes feminism, and feminists, as undesirable. Even in my generation, there’s the trope of the “crazy blue-haired feminist,” also known as the “crazy, untamed feminist who dyes her hair outrageous colors and gets 'triggered' by everything boys say.” This may just seem like a conventional teen joke, but it's used to invalidate and even shame teenage girls for actively speaking against misogyny. The stereotype of the angry or “triggered” feminist sets up a bias fallacy: that because we have strong opinions, we are biased, and if one is biased, one is wrong.

But having a bias does not make us wrong. And being angry does not make us crazy. It makes us passionate, and we are experts on our own experiences. I have grown up watching my mothers get angry and do something constructive about it. I have watched my moms treat patients with cancer, fight in court to get people out of jail, and create public radio journalism; they have proven to me that we need more matriarchal leadership.

Silence and falsities around matriarchies in families and governments lead women and girls to doubt their leadership abilities. But by spreading stories like that of Lilith and abolishing the outdated idea that men are the only effective leaders, we can pave the way for young girls and women to understand their value as outspoken leaders for change.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

Very well said!!!

This is incredible!