"Invisibility Cloak": Uncovering My Identity as a Descendant of Soviet Jews

I’m the daughter of an immigrant family, the product of an undying thirst for a place to call home. My mother was raised in the Soviet Union, where antisemitism underscored the social system, ranging in severity from limitations in universities and jobs to open slurs and violence. A whole ancestral line of mine consisted of rabbis and rebbetzins, including my great grandparents; but as soon as Stalin entered the picture, those caught learning Torah or smuggling matzah from underground ovens on Pesach would be sent to the Gulag. When my grandparents, mother, and uncle immigrated here in 1980, however, the US proved to be prejudiced as well. My family had pictured it as a land flowing with milk and honey where they could express themselves unabashedly; instead, it revealed itself to be a disquieting scene with more subtle, less systemic, but vicious antisemitism. This mutated form of hatred was enough to dissuade my family from becoming observant again.

Nothing appealed to them more than the idea of an invisibility cloak: my family strove day and night to assimilate, Americanize, and conceal their thick accents. This repression was so thorough, so visceral, that my mother only learned of her Jewish heritage accidentally at the age of seven. One day, in sunny Nebraska, the kids at her school ran down the halls, shouting, “K*kes! K*kes! The Jews are evil! Let’s get rid of them!” My mother returned home and announced to her parents and brother, “The Jews are evil! Let’s get rid of them!” My uncle snickered. “Getting rid of yourself then, huh?” My mother’s cheeks turned a deep red. She was embarrassed both because of her cluelessness and also because she was the target of her friends’ chants. Apparently, she was “evil,” and her friends wanted to get rid of her.

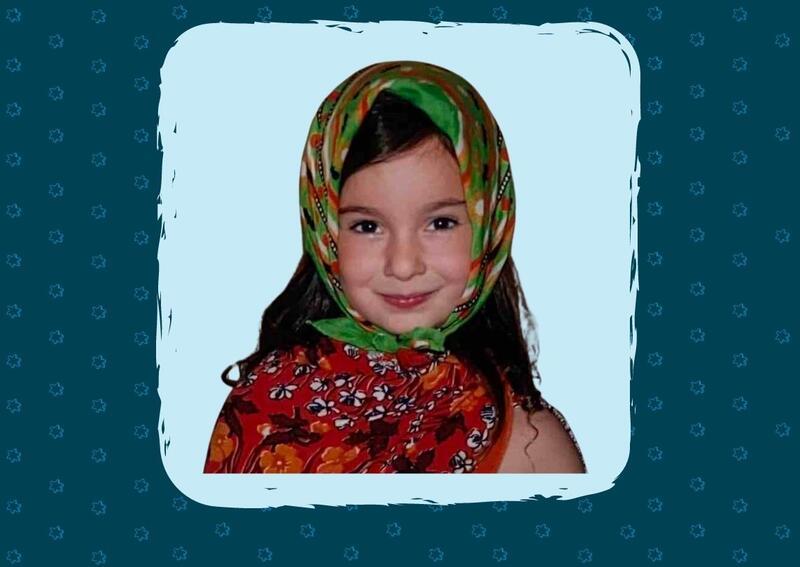

Early on, my mother bequeathed to me this invisibility cloak. As an adult, her Jewish roots were no longer a source of shame, but she still swept her identity under the rug so it was out of sight and out of mind. All I knew was that I was Jewish and that this made me an outlier.

For the first seven years of my life, I didn’t keep Shabbat or kosher, I didn’t attend a yeshiva or shul, and I didn’t pray tefilla (morning prayer) or mincha (afternoon prayer). I was entirely disconnected from Judaism, from my great grandparents who sacrificed everything to call themselves rabbis and rebbetzins and who had been suddenly stripped of their faith. The blows of the Jew-hating iron hand my family once lived under left a gaping hole. Antisemitism’s indelible imprint festered. I eyed the invisibility cloak.

When I turned eight, my father disappeared without notice. My mother, devastated beyond words, wouldn’t leave her room, eat, or talk to my sister and me. When I put my ear to her door and listened very, very closely, I heard faint whimpering emanating from the other side. She didn’t know what to pour her emotions into, where to seek refuge.

Several weeks later, she got all dressed up, emerged from her hibernation, and abruptly proclaimed that we were going to shul. “What?” I asked. “Why?” She sighed: “Because it’s all we’ve got.”

We started going to services every Saturday, spending Friday nights at the rabbi’s house, and studying at Hebrew school on Sundays. Shabbat, eating kosher, and prayer became constants in my life. The purpose my mother found in these communal practices, even aside from the religious aspect, seemed to console her. It was something she could clasp onto tightly, something to depend on, a shoulder to cry on.

I didn’t want to complain; she seemed so happy, which was rare at the time. But I didn’t want any of this. I hated wearing skirts that pooled on the floor, taking days off to fast, and not being able to text friends on the weekend. I felt alien, completely othered by our newfound orthodoxy. So I used the invisibility cloak as often as I could, keeping my Judaism at arm’s length from my life and myself.

For five years, day in and out, I wore the cloak when I could. That is, until one Shabbat morning. The rabbi was giving a d’var Torah about the story of Rachel and Yakov and their love for each other. My mother had seemed fine—whatever that meant at the time—before we left for shul. All of a sudden, though, I could feel her quivering beside me. Soon, she was shaking uncontrollably, and before I knew it, wailing. The rabbi, now alert to my mother’s cries, put the kibosh on his oration and ran over to the women’s section.

I had no idea what to make of the situation. I couldn’t pinpoint what triggered the outburst. Was it the d’var Torah? The story of Rachel and Yaakov? The discussion of a love that had eluded my mother? Perhaps the bottle in which she’d too long stored her emotions finally shattered—a bubble burst, a switch flipped. My mother always put on a bright face and made it through each day without so much as a complaint. So before then, I’d never seen her like that. I was paralyzed. I simply stood next to her and closed my eyes.

When I opened them, the whole of the congregation—men and women, rabbis and rebbetzins, and children alike—had piled atop the two of us. Their eyes were closed too, with their eyebrows furrowed and cheeks puffed from the salt of their tears. A swell of loving-kindness overwhelmed my mother and me.

That was the moment I recognized just how mistaken I had been and just how much I had taken for granted. I’d never given myself the opportunity to experience the Jewish community, and here I was, awestruck the second I truly laid my eyes on it. I beheld the power of Judaism as a coping mechanism, support system, family, and, most importantly, a place to call home.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

What a wonderful well written piece! I too found life in the Jewish community during the dark times of my life!

This is very beautiful, Sarah. Thank you for sharing it with all of us.

Sarah, Your story, so beautifully written, and so poignant, brought tears to my eyes. May you continue to feel the embrace of the community as you forge ahead learning and building your life's dreams.