Leslie Feinberg and the Power of Queer Jewish Memory

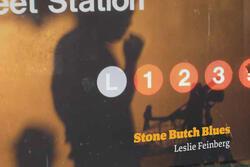

Almost all of the queer people I know can honestly say that reading Stone Butch Blues changed their lives. I know it’s hopelessly overdone to claim that something changed your whole life—it’s a big statement to make—but I can also say it about this book. I read Stone Butch Blues in one sitting during my freshman year of high school. As a trans person who was out to few people, a bisexual intensely ashamed of my attraction to women, and a Jew who hated myself for my Jewishness, reading this novel about a Jewish trans lesbian written by a Jewish trans lesbian made me feel, all at once, not alone in the world.

Leslie Feinberg, the author of Stone Butch Blues, described the book as a “bridge of memory.” Feinberg, who identified as an “anti-racist white, working-class, secular Jewish, transgender, lesbian, female, revolutionary communist,” devoted hir life to revolutionary causes including pro-Palestine justice work, antifascist and anti-KKK action, union organizing, and trans liberation. Zie was an activist in the Workers World Party and wrote several other books, including Trans Liberation and Transgender Warriors. At the heart of hir work was an emphasis on solidarity, radical love, and the documentation and remembrance of queer and communist histories. “Recovering collective memory [how groups remember their pasts] is itself an act of struggle,” Feinberg said in hir afterword to Stone Butch Blues. “It allows the generational currents of the white-capped river of our movement to flow together—the awesome roar of many waters.”

Collective memory, or the lack thereof, feels central to my experience as a queer Jew. Any sense of memory at all feels alien to me. I am the descendant of Holocaust survivors, and for the past few years, I have been trying to document my family history—only to be met with a glaring nothingness, an absence of papers, and in some cases, literal deletion of my ancestors’ names from records. It’s painful to hear my friends talk about how they can trace their family trees back to the 15th century when I don’t know the names and places that define my nebulous familial past. Memory is replaced with violence and erasure. Additionally, as a queer woman who grew up not knowing any queers, not seeing queers on TV or in books or in history, or even hearing the words “gay” or “transgender,” my sense of rootedness to my community’s past feels nonexistent. In that sense, memory is replaced with painful silence.

Leslie Feinberg changed so much for me. After reading Stone Butch Blues, I feel like, finally, I have a history and a sense of memory. Even if that memory is not mine—I'm not related by blood to any of my queer ancestors, and I don’t know the characters and their histories outside of the pages of the book—the narrative makes me feel less alone. Maybe that was Feinberg’s goal in writing the novel: to ground us in some small fragment of a possibly-fictitious past. The movement is inseparable from history, and it’s also ours to shape.

So, what are we supposed to do with collective memory, these breathing documents of history and of forgetting that we hold in our bodies and spaces? Memory helps me, as an activist and communist and person who cares about justice and healing, begin a process of “constructing a future history,” in the words of anthropologist Lewis Borck. Remembering, and filling the holes in our communal memory with love and hope and yearning, cultivates the revolutionary imagination. Scholar and writer adrienne maree brown says: “We have to get into the game of imagination…We have to shift how we think of ourselves, how others think of us, how we think of conflict mediation and resolution, how we think of guns, how we think of safety. We have to imagine new contexts for all of these things if we hope to have a future in which we survive with each other.” Imagination—or the creation of an antithesis to memory, if you will—is the basis of revolution. Through hir writing and activism, Feinberg encourages us to imagine new, more accepting worlds shaped by the fruits of queer struggle, and helps me imagine my queerness and Jewishness as identities not only marked by suffering but shaped by suffering and love, creation, and beauty, where before these identities had been such markers of pain.

Memory doesn’t always have to be revolutionary. Sometimes it can just be comforting (which, you could argue, is revolutionary in itself). I feel simultaneously comforted and isolated by the novel. It’s hard that these narratives are so scarce. But that rarity also makes me feel so much more comforted—because I feel, and have always felt, like a rarity myself. Leslie Feinberg makes me feel like less of an anomaly as a trans, queer, sapphic, anti-Zionist, communist Jew. And that anchor to memory, that challenge to otherness as a feeling and a structure, is both a comfort and a revolution.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

This piece is personal and yet incredibly relatable as someone also looking for my own piece of history. Thank you for your wonderful writing.