A Jewish Feminist and a Feminist Jew

My Jewish and feminist identities have always intersected and supported each other. There was never a moment at my synagogue or throughout my years of Jewish learning where I felt like I couldn’t be a feminist and be Jewish. I was privileged to have strong female Jewish role models who taught me that my femininity could tie me even closer to Judaism. Every time I wrapped my tallis around my shoulders, I felt generations of strong Jewish women embracing and supporting me.

Last year, I was accepted into a political engagement fellowship program. I quickly grew close with the other participants and we all enjoyed learning from each other. One day, we brought up the topic of feminism and what it means to us. It was a progressive, leftist space, and for the past two weeks, I’d felt totally comfortable speaking in it. But when I started to discuss how my Judaism and feminism intersected, the others immediately shut me down. I guess no one in the program had realized that I was Jewish before that conversation. I wasn’t hiding it. Maybe they couldn’t see the silver Magen David around my neck. Maybe they just didn’t want to. They said I couldn’t be Jewish and be a feminist. They said that “Jews oppressed women” and were “colonizers.” I was shocked.

I sat there in silence. I didn’t know what to think or how to feel. In just a few sentences, my peers had made my sense of self shatter around me. I began to question if I really could be Jewish and a feminist at the same time. And the second I began to doubt myself, the warm comfort I'd felt from my connection to those generations of Jewish women before me fled, leaving me alone and confused.

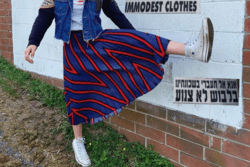

As I experienced similar situations again and again, something became clear: I could be a progressive feminist in these spaces—as long as I hid my Judaism. So, I slowly began to separate these two identities, taking one off and putting the other on as I moved throughout my world. When I went into feminist spaces, I tucked my necklace into my shirt, pushing aside my frustration as I dove into conversations about intersectionality.

A few months later, I was on a Zoom call with my cousins. For some reason, we were talking about antisemitism. “That’s the thing about being Jewish,” my cousin joked, “someone, somewhere, will always hate you.” He was kidding, but there was truth to his words, and they struck me. I realized that I can’t go my whole life hiding an integral part of who I am because I’m afraid of what others will say. When I make space for my Judaism and feminism to support each other, I am a better Jew, a better feminist, and a stronger advocate (not to mention, a more authentic version of myself).

I know that I’m not the only Jewish person or Jewish feminist who feels alienated in progressive, leftist, and feminist spaces. This othering, I believe, stems largely from a lack of education about Judaism. Now, instead of hiding, I try my best to find compassion and educate my peers. When I’m told that I have to “abandon my religion” in order to be a feminist, I explain that my Judaism has actually been full of feminist teachings, role models, and ideas (not to mention the fact that Judaism is an ethno-religion and I can’t change my ethnicity). When someone says that all organized religion is oppressive to women, I explain that I have only ever felt empowered in Jewish spaces, though the same can’t be said for secular feminist ones. When someone says to me that “all Jews are racist,” I don’t ever make excuses for or deny the immense white privilege that many Jewish people have, but I explain the statement’s injustice to the rich and diverse multi-racial global Jewish community. All of these ideas come from misinformed stereotypes about Judaism. They are not only harmful because they misrepresent a community, but also because they erase feminist Jews and Jews of color.

It’s exhausting to constantly justify your identity and explain to the people who are supposed to be your allies why your religion and ethnicity actually support your feminism and activism rather than detract from it; but I would rather do that than tear apart who I am to make other people more comfortable.

Judith Plaskow said, “I am not a Jew in the synagogue and a feminist in the world. I am a Jewish feminist and a feminist Jew in every moment of my life.” Ultimately, it doesn’t matter if my identities don’t make sense to my peers; the only person that needs to be comfortable with them is me. And I am a proud Jewish feminist.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.