Feminism: More Than Just a Lens to View the World

This month our Rising Voices Fellows are examining how their Jewish and feminist identities intersect. Be sure to check the JWA blog each Tuesday for a new post from our fellows—and check out the great educational resources provided by our partner organization, Prozdor.

Somewhere towards the end of my freshman year of high school, I became the class feminist. You know, the girl who always has to speak up about slut-shaming and rape culture and “where are the women in this narrative?”

I had begun to read feminist blogs, and the critical gender lens they used on everything from history, to clothing, to everything in between rapidly became part of my worldview. Right as I was hitting my stride as “that angry feminist,” I studied in the Dr. Beth Samuels High School Program at Drisha in New York.

In addition to being a feminist, I was (and remain) a lover of Talmud. Spending the summer with other girls who took Judaism and Jewish text study seriously was a formative experience for me.

The erudite feminist women who taught us became my role models. (It was not unusual for us “Drishettes” to enthusiastically exclaim to one another that “I want to be insert-name-of-teacher-here when I grow up!” after a particularly great class.)

That first summer as a Drishette I gained facility and comfort with Jewish text. The access to law and tradition that I acquired at Drisha has been fundamental to my practice of Judaism, and has served to make my experience of religion an inherently feminist one.

Upon returning to my Orthodox day school after that summer, I was struck by the contradiction between the access to text I had had in the beit midrash (house of study), which was supported by my school and community, and the access to ritual I had experienced for the first time that summer, receiving an aliyah in a partnership minyan.

The next two years of my high school career would be spent struggling to gain more ritual access within my Orthodox community. While I was given more and more opportunities for high-level text study, and read more and more independently, I was simultaneously being treated like a second-class Jew. What good was my independent-study Talmud class if I did not count when my classmates gathered to pray? Why should I, who had more facility with Biblical text and commentary than most of my male peers, be denied the skill and opportunity to read from that same Torah at morning minyan?

Over the course of that two-year struggle with exclusion, I identified myself as a proudly uppity, proudly Orthodox feminist. I was a supporter of partnership minyanim and maintained that halakhah would eventually evolve to support women’s full religious equality, but that it was a slow process.

This past summer, as a Bronfman Youth Fellow, I traveled to Israel with 25 other Jewish high school seniors, from across the denominational spectrum. A journal entry from the first day of the trip records that, “people keep asking if I’m Orthodox. I figure that since thinking of saying yes makes me squirm, I’m not.”

A shift had occurred.

After further study and reading, I had become convinced that to treat women as anything less than full adult members of the Jewish community was morally and halakhically unjustifiable.

Women today have a social status that would be unimaginable to the sages and rabbis who compiled the Talmud and who ruled based on halakhah. Halakhah requires a seismic paradigm shift to accommodate for that reality. Women’s “exemption” from the performance of certain mitzvot (commandments) is based on a social reality that no longer applies, and today’s woman should be treated as an entirely different legal entity, from a Jewish perspective.

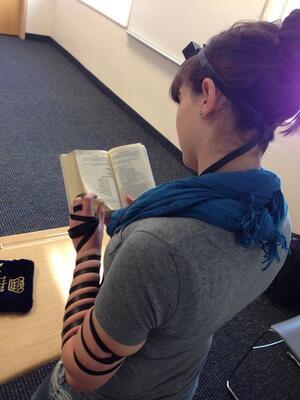

I now prefer to pray in a setting that counts women in a minyan and allows us to lead any part of the service. In keeping with my belief that traditional exemptions of women are no longer valid, I wear tzitzit and lay tefillin, practices I began last summer.

To paraphrase a counselor from this past summer, feminism is more than a lens through which I view the world—“it’s my eyeballs.” I cannot approach Jewish life and text without a feminist perspective, and I hold myself—and the communities in which I place myself—accountable for the moral demands made by feminism. Feminism has been, and remains, an integral part of my religious practice and experience.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

If you have not yet read Gender and Tefillin: Possibilities and Consequences, by Rabbi Ethan Tucker, I strongly recommend that you do so. Shira Salamone, of On the FringeÌ¢âÂÛAl Tzitzit

In reply to <p>If you have not yet read by shirasalamone

Thank you! I read it and loved it.