From 'Rifka' to a Lifelong Love of Jewish Books

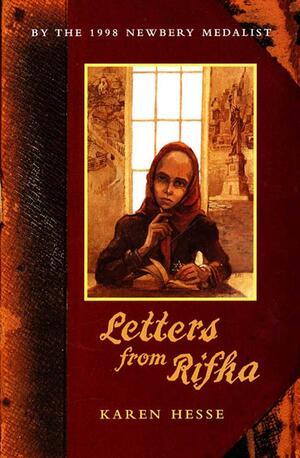

I don’t know how I came to have the book. Did my mother bring it home for me? Did I purchase it at a school book fair? In the end, it doesn’t matter; I’m glad it ended up with me.

Letters from Rifka by Karen Hesse is a children’s book about Jewish immigration to America, antisemitism, and perseverance in the face of obstacles. It’s also about a young Jewish girl who writes and reads and challenges the systems she was born into. Set in the early 1920s, Rifka and her family must leave Ukraine for America once pogroms become too great a threat. The only one in her family with blond hair and blue eyes—stereotypically un-Jewish features—Rifka begins the story distracting Russian soldiers so her family’s hiding place won’t be discovered.

The family faces many trials; Rifka is even barred from joining her family in America after contracting ringworm, and she spends a year in Belgium, adapting to her unfamiliar surroundings and to the hand she’s been dealt. In the margins of a book of Pushkin’s poetry, Rifka writes letters to her cousin back in Ukraine to find comfort, and eventually begins to write her own poetry. She chronicles her arduous journey, longing for the day when she will be safe with her family, free from fear and persecution:

“So many new things fill my life, Tovah. I need to remind myself of how we struggled in Berdichev. If it were not for the Pushkin, and for these letters to you, I would sometimes think I had dreamed all the terrible things about Russia. But when I read the Pushkin, I know my memories are real.”

Rifka shows immense strength, cleverness, and kindness as she navigates the world around her. It is the same world that some of my great-grandparents were thrown into, immigrating from Eastern Europe to the US in 1920, young people driven from their home. I can’t help but think how my family and Rifka’s so narrowly escaped the near obliteration of Jewish Europe.

Rifka’s curiosity and connection to writing resonated deeply with me. Even at a young age, I wanted to know why things were the way they were, especially when it came to the Jewish people and our history. I was lucky enough to grow up in a very Jewish community, but even as a child, I began to understand that being Jewish went deeper than eating certain foods or having a bat mitzvah or feeling a little left out at Christmas.

I had no idea at the time, but reading Letters from Rikfa would set me on a path that I would only begin to understand a decade later. At seventeen, I began to realize the profound impact that Jewish books had on my life after participating in a summer program at the Yiddish Book Center. After this life-changing program, I attended Smith College, a historically women’s college just minutes from the YBC. I felt empowered by the school’s Jewish Studies program, but more importantly, Smith’s community of intelligent and driven people, all of whom were committed to fighting the norms of patriarchal academia. I longed to be around other people who wanted to bravely march into the world, full of new ideas.

Looking back, Smith students remind me a lot of Rifka. At Smith, I was able to speak confidently, make mistakes and learn from them, and pursue what I was truly passionate about. I spent my college years immersed in Jewish Studies, reading Abraham Sutzkever and Dara Horn, learning new languages (another similarity to Rifka), and traveling around the world to dig deeper into Jewish history and identity. After graduating, I began working at Jewish Book Council (JBC), a nonprofit focused on promoting and uplifting Jewish literature. My first Jewish book led me to a life of Jewish books, a life of learning and grappling through reading and writing.

One amazing aspect of JBC is that it is woman-led—the founder of its forerunner, Jewish Book Week, was Fanny Goldstein, a Boston-based librarian who understood the importance of Jewish literature even in 1925, and currently, all the staff members are women. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I ended up at an all-female workplace; I think I intentionally put myself into an environment with people who think like I do, people who want to tell Jewish stories because they find meaning in them, too.

Jewish literature has always been important to Jewish women, because it’s a catalyst for progress—new ideas come from the words and thoughts of the community. It is through books that Jewish women have been able to criticize both the Jewish and secular worlds and the barriers within them, as well as create new perceptions of what Jewish women could be. Rifka is able to save her family and navigate a new world, pushing back against the victimhood she faced in Ukraine; she challenges norms around beauty, religious tradition, and prejudice. It was through Jewish books that I, and many women like me, learned to challenge the world around us, just as Rifka did.

Both personally and professionally, I’m plagued with many of the same questions about antisemitism and prejudice as I was when I first read Letters from Rifka, still wondering why these systems exist and how to dismantle them. The years of studying antisemitism and Jewish history have given me the context to understand modern-day antisemitism and its many complexities. I see Rifka’s story mirrored not only in my own family history, but in the immigrants and refugees of today, who struggle to navigate a world hell-bent on painting them as an “undesirable other.” I think of the many people around the world who have been displaced and killed due to violence and prejudice, Jewish and non-Jewish. I think about Palestine and Israel and the right and desire to belong somewhere, safe and free. These stories, both real-world and fictional, helped me figure out what it means to be a Jewish woman, but also began to show me where I fit into the broader world, beyond this one identity. I’m beginning to understand how they all connect, these threads of history and memory and culture that are woven into our collective lived experience.

Rereading Letters from Rifka recently, I was struck by how much I still see myself in Rifka; or, rather, how much I see Rifka in myself. She has been with me as I’ve grown up, a constant companion, guiding me towards more stories like hers. What is it about these kinds of stories that move me deeply? I think it’s that they bring me back to my Jewishness. Whatever disconnect I felt from my Jewish community (something many young Jews experience, especially women and gender-nonconforming people who feel isolated or excluded from much of the traditional Jewish world), I overcame through my love for Jewish literature. I’ve gained so much insight from my passion for Jewish books. I’ve learned that the Jewish community is not a monolith, that it is diverse and beautiful, much bigger than the American-Ashkenazi culture I grew up with. And it is always changing. There will always be new questions and obstacles and stories to tell.