Rethinking the Canon: Today's Moroccan Jewish Women Painters

About two months ago, the Buenos Aires National Museum of Fine Art opened an exhibition called El Canon Accidental, or The Accidental Canon. It features women artists' works in the permanent collection (1890–1950), many of them exhibited for the first time, and questions the place of women in canonical art. The Western canon is very European, very white, and very male, and as such, when it does venture to depict other cultures, it often does so through a Eurocentric lens. But these women offer new perspectives and often portray their own cultures in their work. Visiting this exhibit inspired me to explore canonical and modern depictions of an often exocitized people: Moroccan Jews.

My first stop was a quick tour of the Louvre, which is possible to visit virtually. This is the very heart of the Western canon, and I honestly wasn’t expecting to find Moroccan Jewish women artists among the French masters. Rather, I was looking for a famous painting from 1839 by Eugène Delacroix: The Jewish Wedding. The oils in the Red Room, where the painting hangs in the Louvre, are full of sexy, exotic bathers and Greek goddesses. Then, amid this beauty contest, one can find Delacroix’s piece, which depicts a celebration on a Moroccan patio. Middle Eastern men and women attend a party with musicians and dancers, and although the bride and groom have already left the religious ceremony, the guests are still celebrating.

The painting is beautiful, but it gained a place in the Louvre as part of the narrative of orientalism. Delacroix had a good relationship with the Jews of Morocco—he journeyed there with his sketchbook on a diplomatic mission and was fascinated by what he found. However, it doesn't matter how friendly Delacroix was with the real-life bridal party portrayed in the artwork or how familiar he was with the Moroccan Jewish community. The Jewish Wedding still represents an outsider’s perspective of the culture. This painting and other French artists’ representations of Jewish North African culture, which sit in high-traffic museums and are frequently reproduced, indicate how Jewish Moroccan life has historically been presented to general audiences: as other.

As I learned from the Argentine exhibition, the canon responds to political, economic, and gender-specific questions, and it exists to forefront certain perspectives, styles, and agendas, while silencing others. This in mind, after visiting the Louvre, I set off to examine the work of two Moroccan Jewish women who depict their own culture and tell different stories through their canvases, their brushes, and their eyes, challenging the canon.

The first artist, Elisheva Chetrit, was born in Morocco and emigrated to Israel as a child in 1955. There, she married a Moroccan Jew, trained as an artist, and focused on her career as a historian. After completing her thesis about the Jews of Marrakech, in 1997, she painted a whole series about Moroccan Jewish traditions. In her paintings, the wedding celebrations include various events around the bride and her family.

I also had the honor of meeting Tetuan artist Esther Benmaman, who immigrated to Argentina at the age of 20, where she studied interior design, but eventually returned to her childhood love of painting. In her canvases, the bride is the main character, like in Delacroix's old watercolors and sketches. Women are at the center of her paintings, and men are absent.

Both Esther and Elisheva’s Jewish brides are styled with beautiful dresses and jewelry, much like those in traditional Western art. But their brides are painted by Jewish women whose own heritage mirrors that of their subjects, not by men who view them attractive for their youth and cultural otherness.

In A Woman Wearing the Great Dress, Elisheva paints a portrait of a Moroccan Jewish bride that recalls photographs from the early 20th century. At first glance, the painting follows Western tradition. However, the modern staircase and the bride’s friendly smile add notes of humor and irony to the scene. She is not surrounded by traditional stucco walls, but rather by a modern setting; Elisheva is encouraging viewers to see the bride wearing the “Great Dress” as more than an exotic beauty object. Rather, the subject is an active participant in the meaningful cultural tradition of a people.

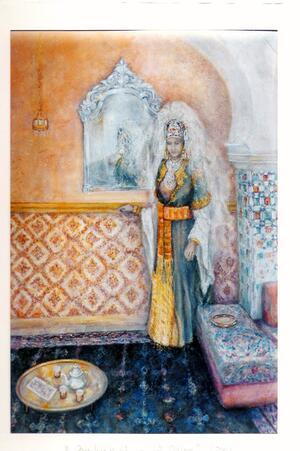

In Esther’s The Berber Bride in the Salon, a woman stands in front of a mirror looking weary. The setting—a typical Moroccan interior—puts distance between the viewer and the exotic bride. Here, Esther reproduces the Western approach to otherness via the traditional interior, dress, and tea set, but as a Moroccan Jewish woman, she’s also intimately familiar with her subject. While Esther focuses on the same material elements canonical painters portray, she is depicting the setting as a descendent of a community that no longer exists, recalling her actual memories of childhood.

It’s not just the different gaze; these painters also give viewers glimpses into private, feminine moments surrounding Jewish weddings, ones that Western artists would not be privy to: the mikveh (Jewish ritual bath) and the henna ceremony. In The Immersion in the Mikveh, Elisheva depicts a young bride taking the ritual bath with a group of women holding musical instruments, smiling and clapping, behind the mikveh. The Moroccan elements appear in the architecture and the clothes and accessories hanging on the wall. The white handkerchief covering the bride’s head represents purity and adds symbolism to the image. In this painting, Elisheva portrays an intimate female ritual, on the one hand, and Morocco's material culture, on the other. The ceremony is not exoticized, but rather represented as a natural scene that conveys intimacy and joy through the colors and the gestures of the figures.

Esther also painted a mikveh scene. She expresses modesty (tzniut) and serenity in her painting. The bride is depicted from behind, covered with a towel walking towards the mikveh—like French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's bathers. But unlike the latter, who focuses on the female body, Esther highlights different elements of the scene through watercolor, and leaves the rest blank, almost like a sketch. This bride is less accessible to the viewer, who cannot take part in the celebrations. Here, the emphasis is on the intimacy of the ceremony, a physical but also spiritual ritual, which contrasts with Ingre’s orientalist portrayal of Eastern bathers as a harem.

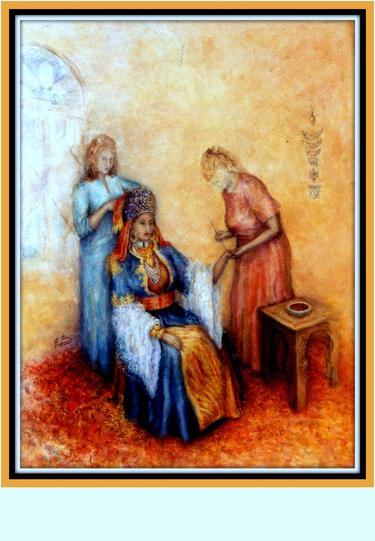

The hennah ceremony is another significant ritual in the context of Jewish marriage celebrations in North Africa. This ceremony aims to protect the bride and the groom from the evil eye and bring them fertility. The celebration was usually held in the presence of many relatives and friends of the bride's family. In Elisheva’s Hennah Ceremony, the bride and the groom are in the center, surrounded by a group of women. Warm colors, a detailed carpet on the floor, the tea set, and stucco decorations create a distinctly Moroccan atmosphere. Esther’s Alheña ceremony is much more intimate and symbolic. Unlike Elisheva's, which focuses on the social nature of the event, Esther’s painting is about the emotional meaning of the ritual. The focus on the bride, her dress, and her jewels, reveals the artist's interest in design details.

The two contemporary artists have different approaches, yet both illustrate the full scope of Moroccan wedding rituals from personal perspectives. Elisheva and Esther, who have been brides themselves, depict the event through Jewish women’s eyes. They respond to the "icon" of the bride through the mikveh, the henna ceremony, the meaning of the dress, rituals, and material culture around the events. In their paintings, as in traditional Jewish life in North Africa, the bride and other women are central agents.

Delacroix’s The Jewish Wedding represents a colonialist, outsider perspective of one of the most intimate traditions in Moroccan Jewish life. And yet, because it’s accepted as part of the canon—officially “accepted” art history—it hangs in the largest, most visited museum in the world. It’s a shame that Elisheva, Esther, and many other artists, who represent their own cultures in their paintings, aren’t offered the same space to showcase their work. The problem is not with Delacroix’s painting itself, but rather whose voices are heard, or rather, whose artwork is visible. Perhaps we need to interrogate who the canon serves and who deserves a place in it.