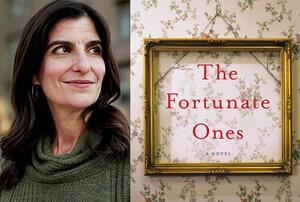

An Interview with Author Ellen Umansky

JWA’s June Book Club pick is The Fortunate Ones, a debut novel by author Ellen Umansky that tells the story of two women, one an older Holocaust survivor, the other a young woman living in Los Angeles, and the stolen painting that binds them together. We talked to Umansky about intergenerational friendship, becoming a writer, and the meaning of the word “fortunate.”

The Fortunate Ones features a significant friendship between Rose Zimmer and Lizzie Goldstein. What, if anything, were you hoping to convey to readers about the nature of intergenerational friendships?

I wish I had a relationship like this in my own life! Alas, I don’t. But I liked the idea that two people, decades apart, could be drawn to each other as friends. I worried that it would seem forced, but I also felt strongly that Lizzie and Rose would be drawn to each other. They share similar traits––they both can be closed-off, reluctant to discuss what bothers them; they both suffered deep losses when they were children––and I felt that Lizzie in particular would be attracted to a friendship with Rose. Yes, because she is a direct connection to the stolen painting that Lizzie feels a lot of guilt over, but also because she’s a tough-minded, clear-eyed person. Lizzie is very much at sea, mourning her father, a past relationship, uncertain what’s next. Rose provides ballast as well as a dose of mystery, gives her an interim purpose, and Lizzie is hungry for it all.

The novel’s storyline largely centers around Chaim Soutine’s painting, The Bellhop. It’s a meaningful and complicated item for both Rose and Lizzie, albeit for different reasons. Was the painting inspired by any particular object in your own life?

That’s an interesting question. I don’t think I have an object that is as fraught as The Bellhop is for both Lizzie and Rose, but I’ve always been drawn to objects with histories––personal or otherwise. When I was a child, I came across an ID bracelet of my mother’s that she had been awarded at Hebrew school. It has a Star of David etched on one side, and her maiden name in script on the other. Even decades ago, it was tarnished, the silver plate flaking off, not exactly fine jewelry. But I loved wearing it, loved imagining my mother as a teenager, long before she had me or my brothers. My mother passed away two years ago, and I take great comfort in wearing her things––whether it’s the watch that she wore for decades or a cardigan that I don’t recognize, but that I like to imagine her buying. These things are both comforting and tinged with inevitable sadness, of course, because she is gone.

Given the content of this book, the title seems to suggest that “fortunate” is a relative term. Was this your intention? As the author of the book and creator of the characters of Rose and Gerhard, what would you say about the level to which they are (or aren’t) fortunate?

Yes, absolutely. A lot of titles were bandied about, and I was so pleased when we settled on The Fortunate Ones (which my friend Jen Albano suggested), precisely because I wanted the phrase to have a sting to it, that it wouldn’t be wholly positive. Neither of the main characters sees herself as particularly fortunate, and given all they’ve endured, who could blame them?

Before I began working on this novel, if you had asked me about the Kindertransport, I probably would have referred to it as a bright spot in history. And it was, unquestionably––10,000 children were saved on the eve of the Holocaust. And yet, also unquestionably, it was horrific for those involved. Families like Rose and Gerhard’s were wrenched apart, and the pain of those separations ran deep, and in many cases, the scars never fully healed. How could they? I was interested in exploring the long shadow of that trauma, how one could be so fortunate and unfortunate, at the same time.

In this novel we see examples of different types of Judaism, and characters whose relationships with Judaism change over time. How has your own relationship with Judaism changed over the course of your life?

I grew up in a Conservative household, going to Hebrew school, celebrating the holidays, keeping kosher––well, a modified form of kashrut; we had three sets of everyday dishes: milk, meat, and the set we used for Chinese food. My observance has certainly evolved, in some ways growing more lax, but also strengthening at times. I’m married, with two kids, and my husband and I have had to make conscious decisions (as one does in adulthood, or at least tries to) about what we wanted our Jewish family life to look like. Our eldest child is about to have her bat mitzvah later this month, so that’s at least part of the answer.

When my mother passed away, I leaned on and took solace in many rituals. It was a relief to have a guide for burial; shiva was, in its own way, a godsend. I said Kaddish for the eleven months––I would often leave my house early in the morning, before the kids left for school, and go to synagogue, sometimes alone, sometimes with my brothers. It gave me time and space to be alone with thoughts of my mother. I remembered my mother observing yahrzeits for her parents; I would think of my own children and wonder how they might mark my inevitable death. It was such a difficult, specific time, but it was also deep and humbling.

What was the inspiration for this story? What led you to focus specifically on the Kindertransport, and the issue of lost/stolen art?

When I was growing up in L.A., my family knew an ophthalmologist who treated my younger brother, and we went to school for a time with his children. He was very successful and wealthy and lived extravagantly: big house in Beverly Hills, chartered planes, and an art collection, the crown jewels of which were a Picasso and a Monet. In the early 1990s, those two paintings disappeared without a trace.

Fast-forward a number of years and I was living in New York, working as a journalist at the Forward where my colleagues were reporting on Holocaust restitution and Nazi-pilfered art. Around this time, the Jewish Museum mounted an exhibit of Chaim Soutine’s work. I had never heard of the painter––a friend convinced me to go––but I was floored by his art and his life story. I started thinking of weaving these stories together into a novel: a Soutine painting, stolen twice.

Was your own family affected by the Holocaust? If so, do these personal connections come into play at all in the book?

Most of my family had left Eastern Europe by the 1920s and were fortunate not to be affected, but there’s a moment I always return to when I think of this question. I was already deep in work on the book, doing research in the archives at the Center for Jewish History, when I came across the papers of Walter Porges, a name I knew very well. Walter was married to my mother’s first cousin. I had forgotten that he had been born in Vienna and gotten out on a Kindertransport.

Walter had a very successful career as a TV news executive, and passed away years ago. I remember hearing stories about Walter producing the news at ABC, but nothing about Walter fleeing Austria when he was seven years old. His parents managed to get out too, but his grandparents did not. Among his papers were letters from the Red Cross, responding to his request for information. His grandparents had been deported from Vienna during the war, and that’s all he knew. He wrote to the Red Cross through the years. There was something so moving to me about these impersonal letters he got back. They spoke to me about the private histories we all have.

What was your path to becoming a writer? Did you always know it was what you wanted to do?

Yes, always. When I was eight years old, one of my mother’s first cousins, Marian Thurm, published a short story in The New Yorker. I remember hearing this and being so impressed. My mother suggested we call to say congratulations. I can remember my mother dialing, handing me the phone (it was a long-distance call), and suddenly Marian went from being my dear cousin to being a WRITER published by the legendary New Yorker. I heard her voice and I was so overcome––I promptly hung up. My mother was mortified. But how could I talk to her like a regular person?

It took me a while to believe that writers resided on earth with the rest of us. I started writing fiction in college. My senior year I won Playboy’s College Fiction Contest, and a short story of mine appeared in the magazine––much to my brothers’ excitement. Several years later, I went to an MFA program at Columbia in writing, and then I worked as an editor in journalism, writing fiction on the side. This book took many drafts and many years to write, and I faced a lot of rejection along the way. It still amazes me that it actually exists as a book, out in the world.

Who are your writing mentors/role models? How have they contributed to your development as an author?

Helen Schulman was a teacher of mine in graduate school. She’s a terrific writer in her own right, but also an insightful and inspiring teacher––a rare combination. I found her guidance and instruction so helpful that I joined two private workshops she led after I graduated. In one, I began writing the material that was the initial gleanings of this novel. When my novel, in an earlier stage, was rejected by a handful of editors and my agent wanted me to start writing something new, I called Helen. (“Just because your agent is tired doesn’t mean you’re tired,” she told me, and urged me to keep at it.) When I sold the book years later, I ran to tell her. In one of our first classes in graduate school, Helen told us to look around the room. “These people will become your best friends, the people you cheer on, the people you call in the middle of the night when you’re terrified you won’t write another word,” she said.

We laughed then, but that’s been borne out and then some. My former classmate Joanna Hershon is one of my closest friends and writing companions. We exchange work, discuss plot points and our children, turn to each other to parse a cryptic note from an editor. In the years it took me to write The Fortunate Ones, Joanna weighed in on countless drafts––so many of what I think of as the better moments in the book sprung from from her smart suggestions. I’m amazed by Joanna’s own work––she has four novels and another on the way––it’s gorgeous and compelling and wise. Writing is solitary business, and having a writer-friend you can lean on to commiserate with, to give you the pointed criticism you didn’t know you needed, to be there when you’re stuck––that makes all the difference in the world.

The Fortunate Ones is a JWA Book Club pick; see our discussion questions for the book.