Frum, fashion, and feminism

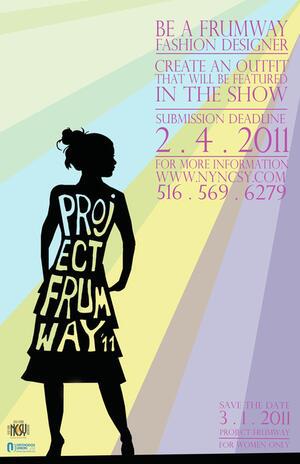

Project Frumway is a charitable fashion show and fashion design competition intended for women of all ages, hosting over 500 people from all over the NY area. This poster promoted the event on March 1, 2011.

Jewish designers are a staple on the fashion scene – famous names like Zac Posen, Isaac Mizrahi, Max Azria, Kenneth Cole, Donna Karan, Calvin Klein, Michael Kors, Diane Von Furstenberg, Ralph Lauren are all members of the tribe. A few years ago, Slate even published a story called “The Rise of Schmatte Chic”, which chronicled the fleeting trend of Orthodox Jewish influence in runway fashion.

Still, high fashion is notoriously synonymous with scant bodily coverage, as evidenced by the vast majority of photos that come out of New York Fashion Week. Perhaps it’s for that reason, then, that high fashion isn’t always equated with the tzniut, or modesty, that many Jews practice.

But lately, modesty-friendly fashion seems to be cropping up all over the place. The most fun example I’ve yet seen is Project Frumway, a take on the popular TV show Project Runway, being hosted by the Orthodox youth organization NCSY.

Women of any age can submit designs, which must meet certain modesty guidelines, such as having ¾-length sleeves, a high necklace and a below-the-knee hemline. The stakes aren’t particularly high: A dressmaker will bring the winning design to life to be modeled at a fashion show at Congregation Beth Shalom in Lawrence, NY later this year. Still, it sounds like a rare opportunity for everyday Jewish women with a knack for fashion to put their talents and style sense to work – without the fear that the rest of the runway will be filled with low necklines and high hemlines.

Recently, Ynet published a profile on Miri Beilin, a Haredi stylist and wedding dress designer who turns current trends looks into modest fashion. Beilin says there is special need within the Jewish community for beautiful garments that are religiously appropriate because women are expected to look their best not just on Shabbat and holidays but during the matchmaking period, the time leading up to a wedding, and more. Of styling her client, she told Ynet, “I won't change her or her personality – just bring out the best in her, physically and personality-wise." Beilin feels she’s doing holy work by helping women feel good about themselves and their appearance.

Modesty fashion is a hot topic among the Jewish blogosphere, too. Popular Orthodox bloggers like Hadassah Sabo Milner of In the Pink and Chaviva Galatz of Kvetching Editor regularly intersperse their usual posts with photos of their own outfits, engaging their readers in conversation about tznius, modesty and other aspects of combining fashion and Judaism. These topics are also find their way onto online forums, which give young Jewish women a place to talk about issues they may face both religiously and otherwise, and to discuss with one another how to best embody Jewish values in a largely non-Jewish world.

I’m a proponent of both fashion and Judaism, as they stand separately. As a Reform Jew and a self-avowed feminist, though, I often find myself frustrated and confused by some of the stories I read of Jewish women who follow strict modesty guidelines. Fashion designer Beilin, for example, says the most important thing to take into consideration when styling her clients is what their husbands will want or like – which, of course, inspires a rant from the independent woman within me about how I can’t believe that we still live in an age where so many women see themselves first and foremost as their husband’s wives.

Yet many women who dress tzniusdik claim that their fashion sense and their sense of feminism are not mutually exclusive. They say that embracing modest dressing allows them to focus on life’s more important aspects. One woman writes, "By embracing the laws of tzniut, we acknowledge that spirituality is, in its very essence, private and internal. Tzniut refines our self-definition. By projecting ourselves in a less external way, we become aware of our own depth and internality, and are more likely to relate to those around us in a deeper, less superficial manner." Half of my brain buys this explanation, arguing that feminism can come in many forms – but the other half holds fast to my preexisting belief that modesty requirements are outdated, old-fashioned and irrelevant.

I think the emphasis here is on the word “requirements” – I don’t believe that modesty itself is necessarily outdated, old-fashioned or irrelevant, as evidenced by many of the high-necked sweaters in my own closet. To each her own, I say: If modesty is your thing, so be it, and if dressing like a “Jersey Shore” cast member is your thing, so be that, too. But I’ve always believed that feminism means, above all else, the free will to determine what’s important to you and the power to decide for yourself what being a woman means to you. Perhaps, then, it’s not modesty I take issue with – it’s that so many women dress modestly because they feel they have to, as required by their (our!) religion.

I’m interested in hearing from the masses. How do you, Jewesses with attitude, reconcile your religious beliefs with your fashion sense with your feminist beliefs – if at all?

When my daughter was a teenager I was a fierce proponent of modesty -- she and her friends seemed unable to keep their midriffs covered, even in January.

But politically I believe that the body is the site of oppression, and I've made my peace with young (and old) women who choose to bare their bellies and cleavage to the rest of us. It's their right.

That's why I enjoyed this blog so much, it took the whole idea into the realm of fashion, which is, at the core, a frivolous sort of thing, and fun. Some of the designers are asserting that Frum need not be dumpy. Let's hope so. Lots to think about here -- thanks!

Way to hock your blog Ally :D Any thoughts on the comments ...?

Very interesting article - this is something I struggle with a lot. The fundamental point about the mitzvah of tzniut is not just about modesty, but about dressing in such a way that you aren't judged by your external appearance. As such, I wonder if 'fashion', which by definition entirely revolves around expression through appearance, can ever be tzniut, whether modest or otherwise. Whilst I consider myself to be a relatively modest dresser, I don't consider myself to be tzniut, for the very simple reason that fashion is extremely important to me - I revel in the creative process of getting dressed each day! Even a modest outfit that's exquisitely put together will induce judgment by those that see it. By this definition of tziut, can the mitzvah ever be compatible with fashion? In my opinion, no.

Ilana K

Haha, I guess my subject line pretty much says it all. And the blog post I've linked above is my reaction to this blog post, as well as Ms. Sztokman's comment above.

Oy. Vey. Sheesh.

Great Article!! I am a frum personal style blogger and I just wanted to invite readers to experience even more modest fashion over at my blog:

http://modestlyfashioned.blogs...

~Ally

Where do I start? You touch on so many of the contradictions that on some level, I think women have to deal with every day, whatever their faith. I used to wonder (usually when I was poofed out in a deservedly much-lamented bridesmaid's dress) how it was that folks got the idea that women should be used for decorative purposes. I mean, it's one thing to want to look nice and clean and like you generally care enough about the people you're seeing to make an effort, but how did we get from that to wearing colors that matched the calla lilies, the table cloth and the place cards?

That said, I can grumble about how all men look good in a suit till the cows come home and know in my heart of hearts that I only like uniforms on a ball field and will probably love playing dress-up till the chickens come home, too.

Lots of food for thought here. I hope it's a discussion you'll keep revisiting ...

Jodi

You're 100% right that any kind of explanation about spirituality that justifies rules imposed from without (read, men) is disingenuous. Coercion negates any possible genuine spiritual value. Because it's about women trying to find some kind of meaning within a system that is by definition oppressive. And impositions like this, even if somewhere deep down they may have once had value, are completely antithetical to spirituality.

I think that the trend towards the "tzniusdik fashionista" reflects a dual oppression, actually, not any kind of real freedom. If religious women are subject to body rules based on a male-rabbinic gaze on the female body, fashion-conscious women subject themselves to sometimes equally oppressive 'rules' about the female body based on a secular-sexual male gaze. A bikini is in some ways just as oppressive as haredi garb in summer. Same for mini-mini skirts and stilletos. Bad for our health. Just as bad as trying to swim with a skirt and shirt on. It's all limiting women's freedom of movement because of men's ideas of our sexuality.

Liberation from both these sets of eyes would mean that women look internally at their own sense of body, that women allow themselves the freedom to feel what we feel as we feel it, to dress in ways that feel and look comfortable and comforting to us. It's about setting our own rules on our own terms and not dressing or walking or behaving because others expect something from us. That is freedom.

B'vracha, Elana