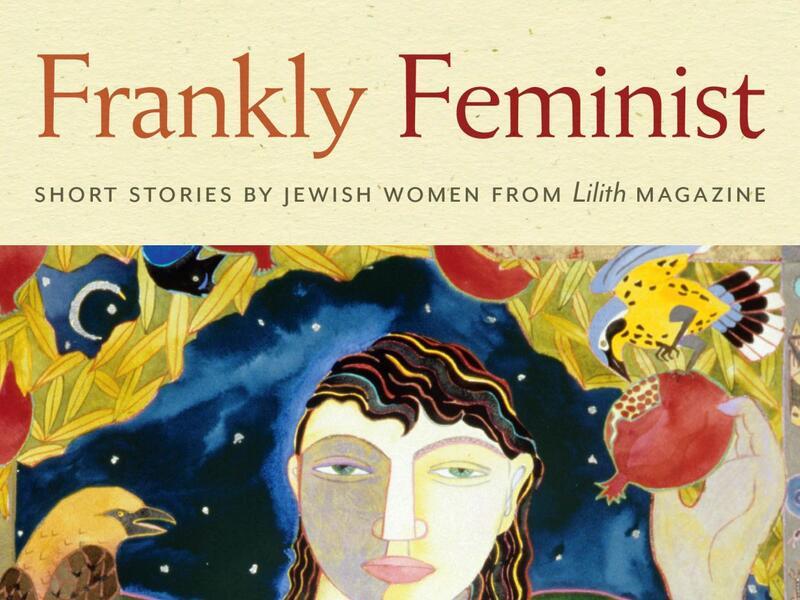

"Frankly Feminist" Invites Us to Explore Jewish Women's Worlds

One of my favorite Yiddish expressions is bubbe meise. Traditionally, it’s been a derogatory term, one that might translate as an “old wives’ tale,” full of superstitious nonsense (presumably in sharp contrast to the nuggets of truth that learned male Jewish scholars offer). But feminists know that the stories of our bubbes, our grandmotherly types, are not nonsense, but rather the stuff of Jewish women’s lives. We value the stories of our bubbes and our maidelehs—our young girls—as well as those of women of all ages. The valuing, re-valuing, and preservation of diverse Jewish women’s stories is the sensibility that animates Frankly Feminist: Short Stories by Jewish Women from Lilith Magazine.

These pages contain 44 stories that Lilith’s editor-in-chief Susan Weidman Schneider and long-time fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough tout “as a unique sampling of the range of stories published in Lilith magazine since 1976.” A bit maddeningly, the year in which each story originally appeared in the Jewish feminist magazine is buried in the writers’ biographical notes at the end of the book. As it turns out, most of these stories were published in this century, 31 of them after 2010 (yes, I’m the nerd that counts such things), and many of them have earned prizes in Lilith’s annual fiction contest. Yet this relatively contemporary collection covers a great deal of historical and thematic ground, demonstrating the capaciousness of the Jewish feminist project.

The editors have usefully divided the collection into six thematic sections: “Transitions,” “Intimacies,” “Transgressions,” “War,” “Body and Soul,” and “To Belong.” But to me, some of the connections across sections were equally provocative. For example, the recovery of women’s stories, as well as what has been lost to history, is gorgeously rendered in Amy Bitterman’s “The Lives under the Stones” (in “Body and Soul”) and Phyllis Carol Agins’ “Flight” (in “To Belong”).

Bitterman’s tale takes us to an underground cemetery, where “every stone tells a story.” And like the gravestones, “the stories press against each other, fighting to be heard, but you only have time for one or two”: that of a seventeenth-century beloved wife and mother juxtaposed with an eighteenth-century kept woman. In “Flight,” Agins introduces us to Hanina, an octogenarian in Philadelphia by way of France and Algeria. In this story that proceeds in reverse chronology, we come to understand that the 13-year-old girl who dreams of “travel[ing] the world . . . like a great explorer” ultimately finds herself “living in a foreign country for the second time in her life . . . when not one of the decisions was hers to make.”

Equally compelling are the stories of women who refuse to do as they are told. Katie Singer’s “News to Turn the World” (in “Transitions”) is set in 1917 but is a disturbingly timely story for this post-Roe era. Here, a mother of many chooses to obtain an illegal abortion. She mournfully shares with her eldest daughter that “[i]t’s too difficult to be a woman sometimes.”

In “The Wedding Photographer’s Assistant” (in “Intimacies”), Ilana Stanger-Ross gives us Dina, whose aesthetic sensibilities are at odds with her job description. “I hate weddings. It’s all such rehearsed performed happiness. Photography should be about capturing something real and true—real emotion, real despair.” When the father of one of her brides has a fatal heart attack at the wedding reception, Dina chronicles his demise, much to the horror of her boss. Yet her steadfast refusal to look away ultimately provides comfort and memory to the daughter bride.

And in Facts on the Ground (in “War”), Ruchama Feuerman provides us with a haunting view of Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza. A divided family becomes a metaphor for a divided nation. The story is told from the perspective of Einat, who regards her family’s dream of a “Greater Israel” as “foolish” and “misguided.” Having outgrown the hypernationalist ideologies on which she was suckled, she is as much an Other to her family as the Israeli soldiers who are preparing to raze her house.

Frankly Feminist certainly contains compelling subject matter and narratives. However, it also provides the pleasure of quirky voices and one- (or more) liners whose value is far above rubies. Ruth, the narrator of Amy Gottlieb’s “Working the Mikveh,” is truly a character. As a mikveh worker and an observant Jew with “a wayward past,” Ruth is invested in ritual, yet views it with more than a bit of irony. According to her, “this is how it goes: menstruation equals dead egg, dead egg equals impurity, no more sex, count the days, visit the mikveh, soak off the world, stand before the attendant, dip once, say a blessing, dip twice more, and poof! Instant purity, body and soul. What better foreplay could there be?”

More serious and heartbreaking is the perspective of a young widow with two children in Racelle Rosett’s “Unveiling.” After a year, Iris still wrestles with the fact of her husband’s death and that she was “meant to step into a future she did not choose and did not plan for, a future that she could barely contrive.”

Jewish feminist fiction is all about inhabiting pasts, presents, and futures that are unchosen, unplanned, and uncontrived. It is also about the choices, plans, and contriving that we do as acts of resistance and persistence. According to Genesis, God made the world in six days, and “it was very good.” The Jewish feminist literary worlds of Frankly Feminist were mostly created over the past two decades, and they, too, are very good.