During Shmita, Finally Learning to Let Go

The past Jewish year was supposed to be a year of rest. It was the year of shmita (Hebrew for “release”), often thought of as the Shabbat year, the Sabbath of the land. As Jews, we’re asked to let our fields lie fallow. Forgive our debts. For me, it’s been a time of taking the Hebrew word literally: This has been a year of release.

Right before Rosh Hashanah last year, my writing partner and I turned in the manuscript for a book we’d been working on since 2019. And right before Rosh Hashanah this year, that book will be released into the world.

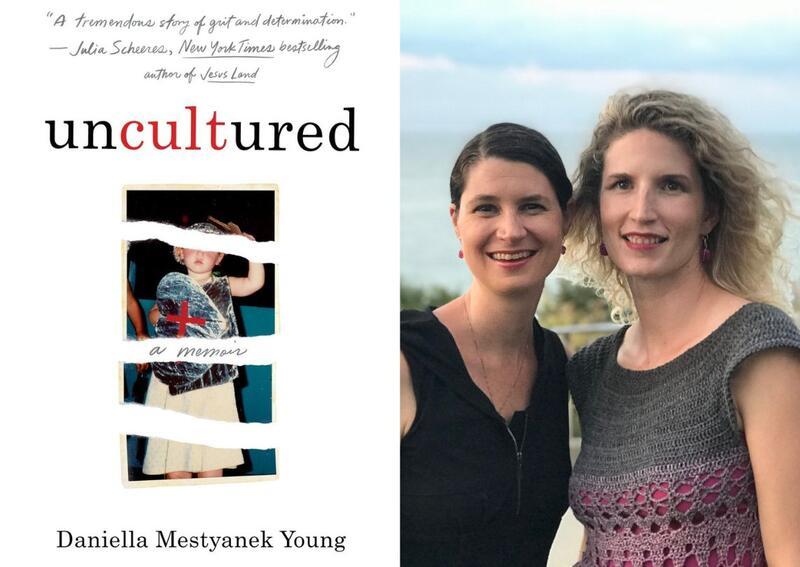

Uncultured is a memoir that tells the story of a woman’s extraordinary life: Born into the Children of God cult, Daniella Mestyanek Young realized as a child that there was no God to be found in the cult’s practice. She got herself ex-communicated by choosing to break the rules that governed every aspect of female bodies, enduring exile as punishment at the age of 15.

On her own with no previous schooling, she navigated high school and college, even graduating as valedictorian. She then made an unconventional choice: She joined the army at the height of the Afghanistan conflict, quickly rising in its ranks to become a leader in intelligence operations and one of the first women in deliberate ground combat on Afghanistan’s soil.

But throughout her service, Daniella noticed terrifying parallels between America’s most beloved institution and the cult she had just fled. In both organizations, women were always less than their male peers and judged by standards and policies that seemed designed to alienate them. In both groups, female sexuality was a threat; while in the cult, women were encouraged to be submissive, in the army, “Don’t get raped” was both policy and a sneer. The misogyny she witnessed and experienced caused her to reconsider everything she thought she knew and, ultimately, to change her life and her career path.

By telling Daniella’s story, we want readers to consider the groups they’ve joined and ask themselves not only how they’ve changed these groups, but how these groups have changed them.

Co-writing this book certainly changed me. You know that proverb “As you teach, you learn”? I experienced that in full force. After we turned in the manuscript, there was an entire year between when the book was “finished” and when readers other than the publishing team would see it. We’d return to the text again and again, reviewing changes for legal, typesetting, design, and proofreading, ensuring our work was as we intended.

It was in those changes, in this year of after and before, this year of shmita, that I started to learn about myself in a new way. I was supposed to be the leader. Daniella was my client; we met when she sought me out to help her navigate the murky world of book publishing, an area in which I’d worked for years. But she ended up teaching me about writing in a way I didn’t expect. Daniella doesn’t love to be called this, but she’s brave in a way I’m not. In a way I admire. In a way I want to be. She tells the truth, on the page and in her day-to-day life. Even the part that hurts, the part that wounds. So often as we returned to the manuscript, I wondered what it would be like if I did the same.

Daniella had noticed things about me, too. She revealed that she’d asked me to write the book with her, in part, because a “nice Jewish girl from suburbia” like me was as far away from her lived experience as she could have imagined. She knew that while I respected those who serve in the military, for me, doing so would be as foreign as joining a cult. She believed that if she could explain her story to me in a way I would understand and connect with, our readers would, too.

I think she was right. The book has been compared to searing memoirs like Educated and The Glass Castle. Early readers are saying things about the book every author dreams of, reviews like: “Readers won’t be able to put down this harrowing and enthralling memoir.”

It sounds weird to say this about a book whose content is (thankfully) far from the Judaism I know, but Uncultured feels very Jewish in its approach. The way Daniella questions her situation at every turn is a lot like the thought-wrestling I love in Judaism, the thought-wrestling that is very much a part of my religious practice. Tashlich, the Rosh Hashanah custom of casting off our sins from the past year, is one of my favorite rituals because it asks from us exactly what I crave from religion: a moment to examine our behavior and to account for it.

It is that kind of contemplation that brought me to reconsider the notion of debt in this shmita year. Debt can, of course, be monetary, but it can be psychological too. The debt I’ve placed on my own shoulders and have carried for the majority of my life was made up of my imperfections, the moments when I failed, when I wasn’t good enough. I believed I needed to be perfect, unfailing, always better than. I avoided asking the hard questions —Good enough for whom? Better than what?—because I knew I had no answer.

And so I’ve spent the past year wrestling with what it would mean if I acknowledged and accepted not only when I had failed, but that I had failed. To forgive myself for being me: a woman in a body who strives to “get it right,” but also a woman in a body navigating an imperfect world.

I thought about why tikkun olam, the act of healing the world, is my favorite Jewish concept. Here’s the origin story I love: In the beginning, God wanted to create a just world, one filled with goodness and loving-kindness. God created a vessel and poured God’s light into it; however, the vessel was too small and it cracked, the shards leaking everywhere. Each act of human generosity uncovers a piece, and putting all the pieces together repairs the broken world.

I thought I loved this story because I like puzzles and because I value compassion and collaboration, working together, the very things that make a co-writing partnership viable. But it’s more than that. The story resonates with me because I believe that every act of goodness—no matter how small—counts, that together, these acts create the world as it’s supposed to be. I like the idea that God needs our help correcting a mistake, that mistakes are part of the re-creation of the world.

This year of release helped me feel ready to take on the metaphorical fields I’ve allowed to lie fallow. In my meditations this year, I felt something close to holiness, as if the reflectiveness of the month of Elul transferred from Shabbat to Shabbat and to all of the days in between. This past year, I’ve asked myself who I wanted to be and why. And I realized I wanted to show up in the world as myself, to share not just what I know, but who I am and what I’ve experienced. To be a little bit more like Daniella, willing to shine light on the good and the bad in the hope that my point of view will help someone make the change they need.

I am ready to begin anew.

So moving. Thank you for this powerful piece!