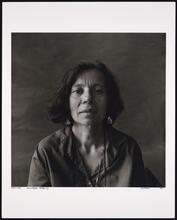

Joy Ladin

Joy Ladin is the Gottesman Professor of English at Stern College, a prolific poet, and a central figure in transgender theology. She has written numerous articles and books of criticism, primarily on nineteenth-century American literature, as well as nine books of poetry. She has also published a book of transgender exegesis and theology, The Soul of the Stranger, a finalist for both a Lambda and a Triangle Award. In her readings of the Hebrew Bible, Ladin analyzes key texts, reinterpreting central Jewish theological concepts from a transfeminist perspective. Her memoir, Through the Door of Life, was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. It details her transition within an Orthodox institution and eloquently weaves together Jewish and transgender themes.

Family and Education

Joy Ladin was born in 1961 to Lola and Irving Ladin in Rochester, New York. Both her parents came from non-observant Jewish households, and both were children of immigrants. Irving Ladin’s family were labor organizers with connections to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. While Ladin’s father was largely detached from Jewish ritual and tradition, Ladin’s mother was committed to an ethnic Jewish identity. To foster her children’s Judaism, Lola Ladin encouraged Joy to attend both synagogue services and Hebrew school.

While Ladin received some formal Jewish instruction as a result of her mother’s efforts, she has also stated that because she did not receive a strong Jewish education, she was able to invent the Judaism she needed. Ladin’s creative theology, therefore, has its roots in her childhood. Her interest in the rituals of Judaism and attending synagogue provided a socially acceptable language for her to articulate her (gendered) differences from her non-observant family. Ladin has also said that Judaism kept her alive during her childhood while she struggled with gender dysphoria.

Ladin left home at sixteen years old to attend Sarah Lawrence College, where she majored in creative writing and social science. After graduation, she moved to San Francisco with her wife and worked in a clerical job at the State Bar of California. Although Ladin published sporadically during this ten-year period, she decided to pursue poetry full-time and returned to earn an M.F.A. at the University of Massachusetts. In exchange for a stipend, she was asked to teach, and her first assigned class was “Man and Woman in Literature.” She was initially resistant but eventually experienced teaching as an authentic way of connecting with people that did not entirely depend on her gender.

Motivated by her love of teaching, Ladin continued her graduate education to earn a Ph.D. in English literature from Princeton. She finished her doctoral degree in five years, completing a dissertation on modernist American poetics and the work of Emily Dickinson. After graduating, Ladin was hired as a professor of literature at Stern College for Women at Yeshiva University, where she continues to teach.

Activism

In addition to her academic work and poetry, Ladin is an activist. She has served on the boards of a number of Jewish queer and transgender non-profit organizations and is a frequent public speaker. She often finds herself bringing Judaism to queer and trans spaces, and queer and trans themes into Jewish spaces.

Ladin has also been a tireless advocate for transgender Jews in settings that are not trans-positive. She is particularly proud of her commitment to teaching about trans and queer Judaism in mainstream and politically conservative spaces and has stepped up these efforts since the 2016 election. Part of her particular gift is reaching audiences who were not previously aware of transgender movements.

Joy Ladin has three children from a previous marriage and is currently married to Elizabeth Denlinger

Transgender Theologian

In her memoir Through the Door of Life: A Jewish Journey Between Genders, Ladin writes about growing up feeling a sense of her difference, without a language to describe her transgender identity. While memoirs are one of the few popular and established genres of transgender writing, Ladin’s memoir was the first of its kind. She lyrically weaves together her transgender and Jewish identities and frames her personal narratives through the lens of her relationship with Judaism.

Through the Door of Life is a memoir, not theology. However, the work explores Ladin’s relationship with God, and one can see early iterations of her theological work. In the chapter “The God Thing,” for example, Ladin describes God’s apparent silence in the face of her alienation as a transgender child. In the wake of her father’s death, she returns to her childhood home and remembers/envisions her childhood self. Ladin’s transition is the miracle that her child-self desired, and Ladin interprets this encounter as God’s silent answer to her suffering child-self. The essay is a potent and moving interpretation of the quality and texture of God’s silences and apparent absences.

Ladin’s work in Orthodox and mainstream Jewish communities has brought her into contact with intense transphobia. In her memoir, she recounts the furor that erupted when she transitioned as a tenured professor at an Orthodox institution, Yeshiva University. She responds to the mainstream media coverage, which was, on the whole, deeply transphobic and transmisogynist. The media, in general, staged Judaism and trans identity as mutually incompatible, and Ladin was placed on administrative leave

Ladin’s most recent book, The Soul of the Stranger: Reading God and Torah from a Transgender Perspective, responds to the supposed irreconcilability of Judaism and transsexuality. The Soul of the Stranger is groundbreaking as the first book-length work of trans Jewish theology and exegesis. Ladin makes crucial interventions into some strains of traditional interpretations of Torah; she creatively reinterprets key passages that have often been deployed against transgender people. For example, one chapter rereads the creation stories in Genesis. Traditionally, Genesis has been at the heart of conservative interpretations of sexuality and gender in United States politics and has been used as the theological underpinning for conservative (anti-gay, anti-trans) legislation. In rereading Genesis, therefore, Ladin is striking at the heart of conservative anti-trans theologies that circulate today.

At the same time, Ladin does not confine herself to the sources that are frequently used against queer and trans people. She audaciously reinterprets the way transgender people and God can share a sense of being a stranger. In addressing the supposed disjunction between being created in the image of God and being transgender, therefore, Ladin reimagines our collective relationship with God.

Significance to Jewish Feminism

Transfeminist poet and theologian Joy Ladin’s TEDx talk, “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Joy Ladin’s theological work is of interest to Jewish feminists because of how she tackles questions of gender in the Hebrew Bible. Ladin’s poetry also merits special attention for Jewish feminists. In her books of poetry, she explores themes of embodiment, theology, and gender from a specifically trans-feminist perspective. Her poetry is foundational in the establishment of trans poetry as a field, and she has written key texts in trans poetics.

In her early poem “The Old God at the Urinal” (Alternatives to History, 2003), Ladin describes a male God spotted in the bathroom. This irreverent poem reveals an early depiction of gender transgression in Ladin’s work, as the image of a masculine God urinating in the bathroom gradually unravels through the course of the poem. The pronoun “He” slowly disappears, until we are left with a pronoun-less God, trying on the underwear of the narrator’s mother in front of the mirror. While this poem is an early effort, it establishes Ladin’s self-conscious feminist engagement with the body of God.

Ladin’s recent project is a series of poems called “Shekhinah Speaks.” The Shekhinah, the traditional feminine image of God, is the subject of Jewish feminist debate. In interviews, Ladin has criticized the conventional formulation of the Shekhinah as binary, where the feminine aspect of God embodies everything that the masculine God does not. In this observation, Ladin participates in a broader feminist critique of the Shekhinah as a largely passive figure.

Ladin reinterprets the Shekhinah as an imminent God deeply embroiled in the lives of Her creations. In the final stanza of a 2019 poem entitled “Comfort Animal,” Ladin writes: “When you suffer, I suffer./ Comfort me/ by being comforted.”( The boundaries between the human and the divine are effaced in this poem, as well as the relationship between subject and object. While Shekhinah is still the creator God, she does not transcend human pain and suffering; instead, she is deeply embroiled in humanity. Thus, Ladin extends the themes of the grappling with God’s nature in the face of human suffering found in her memoir. The ways humans misunderstand Shekhinah forms a central thread through Ladin’s creative non-fiction, theology, and poetry.

At the same time that Ladin explores human/divine alienation, she also finds deep congruence between God and humanity. Both the Shekhinah and humans can experience attenuated relationships with bodies. In one stanza, God comforts us by drawing us to her “invisible breasts,” while in another the human body functions as an “emotional support animal… curled in your lap.” These lines are deeply embodied ways to imagine God and humans, and also images that demonstrate how bodies can be shed. The direct address between the Shekhinah and humans, who misinterpret the Shekhinah’s attempts to communicate, point to the various levels of estrangements we enact: between ourselves and our bodies and between ourselves and God.

In her written work, Joy Ladin consistently takes up the central theological challenges that face contemporary Jewish feminism. She restages the question of God’s body and what it means to imagine the Shekhinah and casts these debates in a trans-feminist light. Her work is essential reading for those interested in contemporary Jewish feminism.

Selected Works by Joy Ladin

Selected Trans Theology:

The Soul of the Stranger: Reading God and Torah from a Transgender Perspective. Lebanon, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2019.

“In the Image of God, God Created Them: Towards Trans Theology.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 34, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 53-58.

Memoir:

Through the Door of Life: A Jewish Journey Between Genders. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

Poetry:

Alternatives to History: Poems. Rhinebeck, NY: Sheep Meadow Press, 2003.

The Book of Anna. Rhinebeck, NY: Sheep Meadow Press, 2007.

Transmigration: Poems. Rhinebeck, NY: Sheep Meadow Press, 2009.

Psalms. Eugene, OR: Resource Publications, 2010.

Coming to Life: Poems. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011.

The Definition of Joy: Poems. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2012.

Impersonation: Poems. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2015.

“Answers to the Name of ‘Lucky.’” Pages 7-25 in Delphi Series, Volume 2. Forsyth, Georgia: Blue Lyra Press, 2016.

Fireworks in the Graveyard. Sequim, WA: Headmistress Press, 2017.

The Future is Trying to Tell Us Something: New and Selected Poems. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2017.

“Comfort Animal.” Poetry (January 2019): 360-361.

Selected Literary Studies:

“A Little East of Eden: Yona Wallach and the Shores of American Poetry.” Parnassus: Poetry in Review 30 (1-2): 327-42.

Soldering the Abyss: Emily Dickinson and Modern American Poetry. Riga, Latvia: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, 2010.

“‘It was not Death’: The Poetic Career of the Chronotope.” Pages 131-155 in Bakhtin’s Theory of the Literary Chronotope: Reflections, Applications, Perspectives, ed. Bart Keunen. Ghent, Belguim: Academic Press, 2010.

“Trans Poetics Manifesto.” Pages 299-307 in Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics, ed. by TC Tolbert and Trace Peterson. Brooklyn: Nightboat Books, 2013.

“Emperors of Ice Cream: Sense, Non-Sense, and Silliness in American Poetry.” The American Poetry Review 43, no. 1 (2014): 31-34.

Ackley, H. Adam, Joy Ladin, and Cameron Partridge. “Trans*formative Teaching.” Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy Vol. 25, No. 1 (Spring/Summer 2014): 86-100.

Friedman, May. “Trans/parent: The Politics of Transition.” Paper presented at “Living Outside the Lines: A Symposium in Honour of Marlene Kadar,” York University, May 15, 2017.

Gailey, Nerissa. “Beyond either/or: Reading trans*lesbian identities.” Journal of Lesbian Studies Vol. 20 (2016): 65-86.

Grossman, Maxine L. “Through the Door of Life: A Jewish Journey Between Genders.” (Book Review.) Transgender Studies Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 4 (2014): 634-641.

Peterson, Trace. “A Literary History of Early Trans Poetry: Readings, Poetics, Transitions, Obstacles, Movements.” PhD Dissertation, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, 2020.

Roundtable on Joy Ladin’s South of the Stranger, with Linn Marie Tonstad, Damien Pascal Domenack, Judith Plaskow, Joseph N. Goh, and M.W. Bychowski. Trans Studies Quarterly 6, no.3 (2019): 409-447.

Selinger, Eric Murphy. “Midrashic Poetry and Ribboni Poetics (With Special Reference to the Work of Joy Ladin and Peter Cole).” Religion & Literature Vol 43, No. 2 (Summer 2011): 135-144.

Singer, Jhos. “A Memoir of Gender Transition.” (Book review of Through the Door of Life.) Tikkun, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Summer 2012): 40-42.