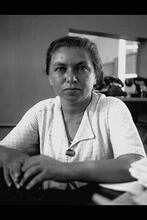

Batya Gur

Israeli author Batya Gur brought literary complexity to the Hebrew mystery novel. Gur wrote her first book, Rezach beShabbat BaBoker (The Saturday morning murder) at age 39 during a break from her career as a teacher and literary critic for Haaretz. Gur is best known for introducing readers to the world of detective Michael Ohayon in a three-volume series that captivated readers. In her mystery novels and later work in non-detective and non-fiction genres, Gur explored the moral questions behind relevant cultural issues, including Zionism and Israeli political history. Gur died in 2005 of lung cancer. She left the world with a written testament to her exceptional ability to imbue meaning in investigative plotlines.

Education and Personal Life

Batya (Mann) Gur was born in Israel on September 1, 1947, to Polish parents who were Holocaust survivors. Although she grew up in Ramat Gan, she went to Tel Aviv for high school at Tichon Chadash (New High School), where she fell under the influence of her mentor Yoska Rappaport. After completing her army service as a teacher in Ofakim, she studied Hebrew literature and history at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, eventually earning her MA degree with a thesis on Natan Zach while teaching high school full time. She also taught writing at the Sam Spiegel Film and Television School in Jerusalem, lectured at Hebrew University and the Open University, and was a prolific book reviewer for Haaretz. She is best known for her series of murder mysteries featuring the detective Michael Ohayon.

Gur was married twice, first to the psychologist Amos Gur, with whom she had three children (Yonatan, Ehud, and Hamutal), and then to Ariel Hirschfeld, professor of Hebrew literature at the Hebrew University. She died on May 19, 2005, of lung cancer.

Early Works

According to Gur herself, she began writing her first book at the age of 39 as a break from her academic studies. She chose to write a murder mystery because she felt expectations were low, seeing the genre “as the least pretentious form of literature” (Jerusalem Report, July 28, 1994, p. 46). Yet from the beginning, Gur’s efforts stretched the formulaic mystery genre toward the more literary novel.

Rezach BeShabbat BaBoker (The Saturday morning murder) made a splash among the Israeli reading public and on the pages of the literary supplements. It introduced the reader to the closed world of the Psychoanalytic Institute in Jerusalem, and to Michael Ohayon, the first original detective in Israeli literature. By all accounts Ohayon is an unexpected character: an educated Moroccan, a literate police officer, and a sensitive “soft-boiled” detective. He is purportedly based on Michel Haddad, a colorful police detective turned private investigator who solved the celebrated cases of the murders of Carmella Ballas and Mala Milevsky, the former a pregnant woman killed by her lawyer lover, the latter a tourist from New York who had survived the Holocaust only to be murdered by two “society ladies” for the money they were to invest on her behalf. The main character also draws a great deal from P.D. James’ fictional detective Adam Dalgleish and even more from Gur herself. The setting of the psychoanalytic institute—a microcosm with its own rules and customs—served Gur well. It limited the number of potential suspects and offered parallels between the process of psychoanalysis and detection, especially Ohayon’s questions (“say anything that comes to mind”) and his ability to evoke transference.

Gur’s second mystery followed on the heels of the first. Mavet BaKhug LeSifrut (Murder in the literature department, translated as Literary Murder: A Critical Case) combines the police procedural with the genres of academic mystery and the roman à clef. It is set in the Hebrew literature department of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and the characters who people the department discuss questions of aesthetics, value, and evaluation as if their lives depend on the answers. In this case, detection is compared to literary analysis.

The third volume, Linah meshutefet (Cohabitation; translated as Murder on a Kibbutz: a communal case), expands the Israeli landscape, taking Michael Ohayon to the A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz, an institution that once symbolized the pioneering efforts of the founders of Zionism but is portrayed in the throes of change.

Novels

Gur’s first non-detective novel, Lo kakh te 'arti li (I didn’t imagine it like this) combines a rumination on gender with other binaries (religious/secular, pragmatic/mystical). The protagonist Yoela is an obstetrician-gynecologist who studies aging and undergoes her own midlife crisis. Her complicated relationships with her mother, her intersex patient, her family, her colleagues, and her potential lover Yoel offer an exploration of the various roles of a woman: daughter, wife, lover, mother, friend, professional.

Even tahat even (A stone for a stone) tells of a bereaved mother’s struggle with Israeli authorities after her son’s senseless death during military service. What seemed initially to be an accident was revealed to be the result of a risky game of chance that translates as “net roulette.” The novel is based on the real-life story of Shulamit Malet, whose son’s 1992 death in the air force led to the charging of three officers and the public’s demand that the investigation of training accidents be conducted outside of the military.

Non-Fiction

In 1990 Gur published Mikevish HaRa’av Smolah (Left from Hunger Road), a memoir based on her army service as a teacher of underserved students in the development town of Ofakim, in the Negev. Originally settled by immigrants from North Africa, textile manufacturing was its main industry.

Gur’s collection of essays M’bli lidaleg `al Daf (Without skipping a page), published posthumously, attests to her breadth as a reader and literary critic. Essays on nineteenth-century classic authors (from Chekhov and Dostoyevsky to Sholom Aleichem and Flaubert) are followed by those on works by twentieth-century poets and prose writers (including celebrated Europeans such as Albert Camus, Thomas Bernhard and Natalia Ginzburg, Constantine [C. V.] Cavafy and Zbigniew Herbert), alongside writers closer to home (Suad Amiry and Emil Habiby) and from further east (Junichiro Tanizaki and Dai Sijie). Each article shows the play of a quick, informed, and insightful mind on a wide range of literature, nearly unimpeachable taste, and the curiosity of a voracious reader. So too, do Gur’s short studies of Hebrew writers, including S. Yizhar and David Grossman, Agi Mishol and Tami Greenberg, Yuval Shimoni, Hanoch Levin, and Sayed Kashua.

Later Mysteries

While the fourth in Gur’s Ohayon series, HaMerhak HaNachon (The proper distance), takes on another closed society (that of a symphony orchestra), her last two mysteries tackled larger social issues: the Yemenite Children Affair (parshat yaldei teiman, the kidnapping of babies born to immigrants from Yemen) and the criminal killing of Egyptian soldiers during the Six Day War. The overtly political nature of these works further blurred the distinction between the mystery and the novel.

Rezach, Mitsalmim (Murder, [we are] filming, translated as Murder in Jerusalem), revolves around the studios of the Israeli Broadcasting System. The television station is another closed community, but one that is open to the outside—and especially its discontents—by the very nature of the stories it reports. This last novel, originally a TV miniseries, was critiqued for being too much about its subtext expressing ambivalence about Israel and too little about Ohayon, who by now had been promoted away from the actual investigation.

Throughout the mysteries, Ohayon represents Homo ethicus, engaging friends and suspects questioning the possibility of living an honest life. “You always live at the expense of someone else,” declares one of the murderers (Retzach Be-Derech Beit Lechem, 2001). Gur’s narratives do not avoid criticizing Israeli society; in the end, Ohayon’s beloved son Yuval, disenchanted, departs for Canada, while the father concludes that Israel is no more moral than anywhere else.

Legacy

Literary critic, high school teacher, and author, Gur pioneered the literary mystery in Hebrew. Until her introduction of Michael Ohayon, the detective novel in Hebrew was mostly limited to early efforts in the 1930s, to the children’s section (most notably the Hasamba series), and to translations. Her first three mysteries were published in quick succession; almost at the same time Shulamit Lapid, already an established writer, and Ora Shem-Or, a long-time journalist and writer, also began their series of murder mysteries. Yet it was Gur, first and foremost, whose detective and whose stories established the genre, captivated the reading public, and set the bar high for all those who followed. “A particularly spectacular and refined detective story,” was the evaluation of literary critic and scholar Ariel Hirschfeld (who became her second husband).

Gur’s work explored the bearing of the past on the present, exposed the corrosive nature of secrets, criticized inflexibility, and questioned the belief in Israeli exceptionalism.

Selected Works by Batya Gur

Retsah beShabat baboker: roman balashi. Jerusalem: Keter, 1988; published as The Saturday Morning Murder: A Psychoanalytic Case, translated by Dalya Bilu. New York: Aaron Asher, 1992.

Mavet bahug lesifrut: roman balashi. Jerusalem: Keter, 1989; published as Literary Murder: A Critical Case, translated by Dalya Bilu. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

Mikevish hara'av 'semolah: temunah kevutsatit 'im nashim, gevarim viyeladim be'ayarat pituah (Left from Hunger Road: group portrait with women, men, and children in a development town). Jerusalem: Keter, 1990.

Linah meshutefet: retsah bakibuts: roman balashi (Cohabitation: murder on kibbutz: detective novel). Jerusalem: Keter, 1991; translation by Dalya Bilu published as Murder on a Kibbutz: A Communal Case, translated by Dalya Bilu. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

Lo kakh te 'arti li (I didn’t imagine it like this). Jerusalem: Keter, 1994.

HaMerhak haNakhon: retsah musikali (The proper distance: a musical murder). Jerusalem: Keter (Yerushalayim, Israel), 1996, translation published as Murder Duet: A Musical Case, HarperCollins, 1999.

Even tahat even (A stone for a stone). Jerusalem: Keter, 1998.

Meragel be-tokh ha-bayit (Spy in the House). Jerusalem: Keter, 2000.

Abramovich, Dvir. "Israeli Detective Fiction: The Case of Batya Gur and Shulamit Lapid." Australian Journal of Jewish Studies, 14 (2000): 147–79.

Berg, Nancy E. “Oleh Hadash (New Immigrant): The Case of the Israeli Mystery.” Edebiyat Vol. 5, (1994): 279-290.

Cooper, Sean. “The Brilliance of Batya Gur, Israel’s Greatest Detective Author.”

Tablet, July 7, 2019

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/batya-gur-israel-detective-novels

Furstenberg, Rochelle. “The New Wave of Israeli Detectives.” Modern Hebrew Literature, 8-9 (1992): 53-55.

Sokoloff, Naomi. “Jewish Mysteries. Detective Fiction by Faye Kellerman and Batya Gur.” Shofar Vol. 15, No. 3 (1997):, 66-85.