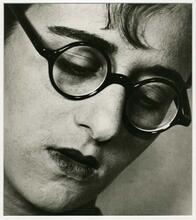

Flora Benenson Solomon

Flora Benenson Solomon’s deep commitments to welfare and Zionism traversed geographical boundaries and social groups. When she was a young girl in Russia, her father’s passion for Zionism influenced her own, eventually prompting her to live out her dreams in Palestine after World War I. In Jerusalem, she fundraised for the Haganah and led efforts to unite Arabs and Jews. In London, Solomon became involved in welfare projects assisting Jewish girls working in East End sweatshops and introduced reforms to improve working conditions at Marks and Spencer. Solomon maintained an unwavering commitment to Zionism, which acted as a sustainer of English Jewish identity until her death in 1984.

Early Life, Education, and Marriage

Solomon was born Flora Benensen in pre-revolutionary Pinsk, Russia, on September 28, 1895. Her beloved, larger-than-life father, Grigori Benensen, made a fortune in Russia’s Caucasus oil fields and Lena gold mines and served as a banker to the Tsar; he inherited a commitment to Zionism from his father. In 1905, Flora’s mother, Sophie (née Goldberg) deposited her at Fraulein Wolff’s school for Jewish girls in Wiesbaden, Germany. At the time, Flora spoke some French but no German. She remained at the school until 1910 with little contact with her family. She returned to the palatial family apartment in St. Petersburg with, as her sister wrote, “a virile mind and iron will under the prim demeanor of a German miss” (Harari, 16). She completed her education with a Russian tutor in St. Petersburg.

In 1914, Flora left Russia with her father to seek medical treatment for him in Germany. When war broke out, they made their way to London and struggled to obtain resources and get the rest of the family out of Russia. Within a few years, Flora became engaged to Harold Solomon, scion of a family of Jewish stockbrokers and a colonel in the British army. She volunteered as a nurse and maintained a lively correspondence with her fiancé while he served in Africa during World War I. His lengthy letters survive, with their detailed descriptions of life in colonial Africa and his promise that “when we do meet sweetheart…I shall make your life one long dream of happiness” (Harold to Flora from Durban, March 12, 1918). They married immediately after the war and soon left England for the place of her Zionist dreams, Palestine, where Harold acted as an aide to Herbert Samuel, the British High Commissioner.

Zionism

In their Jerusalem home, Solomon began her career as a Zionist salonniè re and fundraiser for the Haganah. She welcomed visiting Zionist friends from London like Chaim and Vera Weizmann and introduced them to prominent residents of Palestine. Notably, she brought Arabs and Jews together socially. Palestine also marked the beginning of Flora’s impulse to solve social problems. When she understood that the poor in Palestine poor had access only to contaminated water, she appealed to her father for funds that would support a pasteurization project called “A Drop of Milk.”

In 1921, Solomon traveled to England to give birth to her only child, Peter, then returned to Palestine. Candidly, she wrote, “I have never been good with children, not even with my own son” (Solomon, 62), and indeed, Peter seemed closer to his father until Harold Solomon’s death in 1930. Peter then enrolled in Summerfield (now Summer Fields) prep school, followed by Eton, Oxford, and service in World War II as a cryptographer for the Intelligence Corps at Bletchley Park. Like his mother he showed an early commitment to social justice. In 1961, he founded Amnesty International (he had changed his name to Benenson after his grandfather’s death in 1939). To his mother’s dismay, he converted to Catholicism in 1958.

A riding accident in 1923 left Harold paralyzed. The Solomons returned to London from Palestine, where they effectively began to lead separate lives, Harold traveling in a specially equipped car with friends and nurses, Flora slipping away to stay with family and enjoy social life in Paris. Looking for purpose, she became active in the Butler Street settlement house for Jewish girls working in the sweatshops of London’s East End. She founded the Blackamore Press to “issue foreign classics in English translation” (Solomon, 140). And, in 1927, she began a passionate affair with Alexander Kerensky, a key figure in the early days of the Russian Revolution. The affair lasted until the eve of the second World War and was, she wrote, “not so much a restoration of my sexuality as its discovery” (Solomon, 136). Kerensky shared neither her enthusiasm for Zionism nor her interest in welfare work; they drifted apart as Hitler took hold in Germany and Flora, “in a fit of pique” (Solomon, 164), accused Kerensky of anti-Semitism. Moreover, his “sustained vendetta” against Moscow disturbed her at a time when the Soviets took a determined stand against Hitler.

Marks and Spencer “Welfare Warrior”

Harold Solomon’s death in 1930 and the loss of her father’s fortune in 1931 following the stock market crash left Flora in need of financial support. Encountering Simon Marks at a dinner party, she told him that his department stores Marks and Spencer had a reputation for exploiting its workers and that it was a firm that “gives Jews a bad name.” First offended then intrigued, Marks commissioned Solomon to investigate. Mentored by the notable labor reformer Margaret Bonfield, she visited many of Marks and Spencer’s 160 stores to investigate working conditions. She then toured stores and garment factories in Berlin to study labor practices. With some trepidation, she drafted a searing report for Simon Marks on conditions in his stores. He “endorsed” the report and gave Flora a green light to carry out proposed reforms.

As the sole woman executive in the Marks and Spencer administration, Solomon had an uphill struggle to be taken seriously. Marks and Spencer employed women as clerks, cleaners, and seamstresses with male supervisors. Solomon’s approach as Staff Superintendent of the Employee Welfare Department was to support higher wages and shorter hours. Equally importantly, she felt the firm should make a commitment to the “human dignity” of its workers. Over time, her department supported subsidized staff cafeterias, podiatry services, beauty parlors, and pleasant rest rooms, as well as seaside holidays and holiday camps for its “girls.” She defended birth control instruction in staff clinics, explaining to Simon Marks, “Have you any idea of how many of our girls become pregnant? They can’t afford to give up working, so they keep it a secret till the last moment” (Solomon, 170). Each store had a welfare office where workers could bring personal problems. Workers could not be fired without a hearing by the Welfare Committee (consisting of an auditor, a member of the personnel committee, and a staff representative), which met once a week in London. Over time, Solomon’s efforts gave Marks and Spencer a reputation as a good place to work and a workforce committed to the firm. As she wrote, “News spread that in joining Marks and Spencer, you became part of an extended family” (Solomon, 162).

With the advent of the second World War, Solomon, nicknamed the Lady of the Ladle, used her well-honed skills to open field restaurants for those displaced by German bombs. A joint effort between the government and Marks and Spencer produced hundreds of thousands of cans of “blitz broth,” a nourishing vegetable soup, and Marks and Spencer staff shifted to work in the emergency cafeterias. After the war, the British government rewarded Solomon with the Order of the British Empire (OBE).

Following the war, Solomon made numerous trips to Israel, usually staying with her close friends the Weizmanns (Chaim Weizmann was the first president of Israel, 1949-52). Golda Meir, then Minister of Labor, drafted her to aid Holocaust survivors housed in refugee camps. Drawing on her considerable organizational experience, Solomon set up soup kitchens and medical services, used Marks and Spencer techniques to streamline suppliers, and, equally importantly, developed cottage industries for women—weaving rugs and making pottery. Her efforts resulted in a perceptible rise in morale among the refugees (Weidenfeld, 1994, 200).

During her years first as Welfare Director then as Staff Superintendent of Marks and Spencer, Solomon never lessened her commitment to Zionism. Her elegant London apartment continued to be a place where, as her friend the publisher George Wiedenfeld described it, “Flora was a port of call for Zionist leaders from all over the world” (Wiedenfeld, 1994, 192). Solomon’s autobiography offers insight into the complex Zionist community and culture in twentieth-century Britain. As British Jews became more middle class and less observant, “Zionism provided them with opportunities to express middle class respectability by making charitable donations, and offered many occasions, from at-homes to dancing parties, to spend their leisure time in a way commensurate with the social behaviour of the British middle class at large” (Wendehorst, 315). Or more succinctly, Zionism became “a secular alternative of Jewish identity” (Wendehorst, 315).

Kim Philby Episode

Solomon made headlines in 1962 when she “outed” Kim Philby, the notorious double agent and member of the Cambridge Five, a British spy ring. She had known Philby as a child—his father, Harry St. John Philby, was a British civil servant in Palestine—and was familiar with his left-leaning politics. In 1962, angered by his negative coverage of Israel when he worked as a journalist in Beirut, Solomon told Victor Rothchild, a banker, scientist, and intelligence officer, that Philby was a Communist. Rothchild arranged a meeting for Solomon with British security, which led to Philby’s flight to Moscow (Solomon, MacIntire, Guardian, April 4, 2014).

Flora Solomon died on July 18, 1984. She is buried next to her husband in the Cimetière Israélite de LaTour-des-Peilz, Vevey-Vaud, Switzerland. Shortly before her death, she summed up her life in an interview: “I always had this passion for improving people’s lot” (Jewish Chronicle, June 15, 1984, 24). Her gravestone echoes that sentiment: “where there is no vision, the people perish.”

Buchanan, Tom. Amnesty International and Human Rights Activism in Postwar Britain, 1945-1977. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Carter, Katherine. “Flora Solomon: Welfare Warrior.” YouTube Video, 41:34, March 8, 2021; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aHFWJ24I-Lw.

Loeffler, James. Rooted Cosmopolitans: Jews and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

Harari, Manya. Memoirs, 1906-1969. London: Harvill Press, 1972.

Macintyre, Ben. “My Hero: Flora Solomon.” Guardian, April 4, 2014.

Marks and Spencer Company Archive, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Peter Benenson Collection. British Library unprocessed collection, Deposit 11428 (at the time of publication of this essay).

Solomon, Flora, with Barnet Litvinoff. Baku to Baker Street: The Memoirs of Flora Solomon. London: Collins, 1984.

Weidenfeld, George. Remembering My Good Friends: An Autobiography. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

Weizmann, Vera. The Impossible Takes Longer: The Memoirs of Vera Weizmann, Wife of Israel’s First President. London: H. Hamilton, 1967.

Wendehorst, Stephan. British Jewry, Zionism, and the Jewish State. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.