Diane Arbus and Art as a Means of Processing, Coping, and Acting

The news these days often feels like a slap in the face. With everything happening around the globe, the eternal question is: how in the world do I deal with this? We can donate to causes we believe in, we can talk to friends and family, we can stay as informed as we reasonably can.

Personally, staying engaged and taking active steps for change is always the first place my mind goes. But constant engagement gets overwhelming very quickly. I have responsibilities to my family and friends. I have school, and extracurriculars, and it often feels like I can’t possibly take one more thing before something would have to give. So how can I stay informed and engaged without getting overwhelmed? How can I process constant shocking news without just shutting down and turning away? Diane Arbus has become one of my role models in this endeavor.

Born Diane Nemerov in 1923 to a wealthy family in New York, Arbus was raised sheltered from the world. She once said in an interview with Studs Terkel, “I was confirmed in a sense of unreality. All I could feel was my sense of unreality.” As she stepped into adulthood and away from her family, she sought the reality she had been kept from.

In 1946, Arbus’s husband, Allan Arbus, returned from World War II. The couple soon opened a fashion photography studio. Arbus designed and styled the shoots, while her husband encouraged her creativity and handled the technical side of the business. Though the studio was financially successful, the work was not fulfilling for Arbus. She hated the commercial world and sought to find reality of a different sort.

And so, Arbus split from the studio, and began her own career as an independent street photographer, capturing patrons at gay bars, people with disabilities, “freak” shows, and “freak” museums. Another common subject for Arbus’s work was sets of twins and triplets, in addition to everyday people around Brooklyn and Manhattan.

The transition out of commercial work was not easy for Arbus. A female photographer working independently at that time was very uncommon, and stepping out of Allan’s shadow was a struggle. When she first started working as a street photographer, her shyness stunted her ability to ask people to pose for her, but the longer she worked, the more comfortable she became. Through influence from mentors and friends, Arbus was able to find her style and make a name for herself.

Her interest in photographing what her daughter Doon referred to as “the forbidden” gave her a safe way to see what she had so long been sheltered from. Her pictures consistently have an eerie energy to them, often dark and off-putting. People often felt threatened by the way Arbus captured her subjects, making her very controversial in her time. But to Arbus, her camera was a shield. It gave her just enough distance from her subjects to see their world and the world around her without getting too close for comfort.

As her career continued, she began to see her work as a way to inform others, as well as herself. Arbus once stated that she thought "there are things that nobody would see unless I photographed them." She aimed to shed light on the unseen.

Diane Arbus used her photography to step back, gain a deeper understanding of her subjects, and show what she’d captured to the world. Her photos illustrate bizarre individuals portrayed simply: monochrome, framed head-on. And yet it’s not Arbus’s technique that makes her work stand out. It’s the emotion behind it. It’s the honesty, the rawness of the uncharted world that she sought to reveal.

Arbus struggled with depression for her whole life, as had her mother. She used her art to help her feel, and to help her cope. The pressure and fear that surrounded her dissipated when she entered someone else’s life through the lens of her camera. Devastatingly, Arbus’s depression overtook her coping skills, and she took her life in 1971.

Rather than focusing on her death, I choose to draw inspiration and guidance from the way she lived. Arbus’s career sets a beautiful example of how to create space for purely expressive art. Art as a means of activism and coping is nothing new—yet it often feels inaccessible. Arbus took the risk to step away from commercial work. She used her previous knowledge, took a couple classes, found a few mentors, and pursued photography driven by curiosity and empathy.

Of course, you don’t need to be the next Diane Arbus to create meaningfully expressive art, but we can take inspiration from her willingness to jump in. What would it look like for you to take a step back from fear and pressure and just create? Or even just take a moment to appreciate the beauty in a world often too focused on darkness? It can be freeing and meditative to process life through art.

My mom, an amazing mental health professional and exceptional artist, does Zentangle. Zentangle is a meditative, abstract, shape-centric art form. Time after time, when the world starts to feel too overwhelming, I have seen my mom pick up a pencil and learn a new Zentangle pattern. She spends hours in a flow-state with the pattern: repeating it, refining it, and reinventing it. She has told me that the repetition and the beautiful potential in a not-quite-straight line helps her center herself. Getting into that creative flow-state is so beneficial for her, and a trait of hers I admire.

Learning from her example, I have tried to process difficult news by listening to music. When I’m not in a space (mentally or physically) where I can make art, appreciating art from others feels just as grounding. Lately, the conflict between Israel and Palestine has been a deeply painful reality to swallow for millions of individuals and communities across the globe. Whenever I learn overwhelming information about the recent tragedies in the Middle East, I listen to two songs, on repeat, for as long as I need. The rhythms, the calming vocals, and the hard-hitting lyrics end up concocting a perfectly meditative space for me. Lately, the songs working for me are Call Them Brothers by Regina Spektor and Only Son and Soldier’s Daughter by Jhameel. I don’t know what the artists’ goals were when creating these songs. I don’t know if they would help others process these events the way they help me. The thing is, it doesn’t matter. They help me cope. They may not work for everyone, but they work for me.

In a world that promotes emotionless action, finding what helps you process your environment is crucial. Arbus found her style and stuck to it, even when the emotion of it made others uncomfortable. Whether you’re creating art, appreciating art, or just taking a moment out of your day to breathe, that mindfulness can provide the space often needed to process. And then, if you have the capacity, those active steps for change may not feel quite as overwhelming anymore.

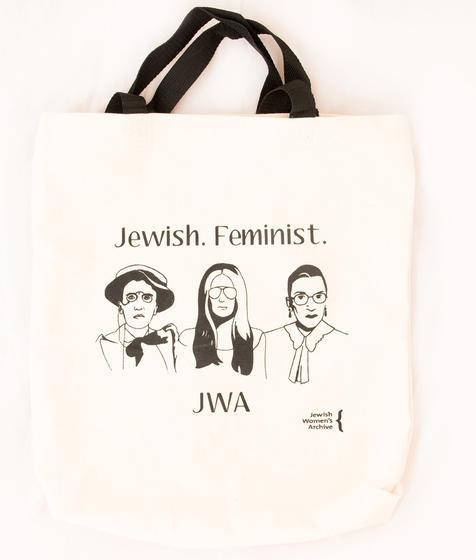

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.