A Defense of Failed Activism

Any activist’s favorite thing to do is be better than everybody else.

Changemaking as we know it has a major flaw: endless ego. Any activist, self-declared or otherwise, who tells you we aren’t obsessed with ourselves is either lying or naïve. Truly humble activists who have been acknowledged as even passably successful do not exist.

Most reading this are now probably dismissing me as harsh, and that is the intentional damage dealt by activists’ self-absorption. We modern activists have molded you, our audience, into staunch defenders of any supposed charity you see. We have done this by convincing you of our own pure motive, portraying ourselves as undeniably altruistic.

Activists as celebrated as Gandhi have paraded themselves as lacking material gain from their actions and implying a complete lack of benefit from their work. The public turns Gandhi and the like into literal icons while he abused the vulnerable behind closed doors. Though Shaun King allegedly stole from his charity’s patrons while Lance Armstrong flat out lied to his supporters, both similarly enjoyed the public’s pious admiration for years as they misrepresented the values they claimed to fight for.

This hero-worship effect is not limited to outright deceivers: Greta Thunberg, for example, invokes the urgency of her own cause to inspire indignation. She criticizes the masses for what she condemns as inaction while in reality most do not have the privilege of fiscal ability to unquestionably support her often-costly cause. Although her motives may be honest, in the pursuit of change she has reached the same result: unchecked idealization. Engaging with humanity in any way has become a bombardment of the self-righteous convincing you of their moral superiority (regardless of individuals’ differing tactics).

Don’t get me wrong; I’m a proud activist and unabashedly loud about it. The issue becomes what activists encourage: being exactly like us.

To be defined as successful, an activist must drive large-scale change. This requires help. Therefore, effective activists must be admirable and inspire others to join them. Consider every piece of news, every good Samaritan interview, and every charity spotlight you’ve ever consumed. Have these earthly angels even once told you to ignore their movement? Have they ever turned away your help, asked you to refrain from contributing? The answer is no. No activist would ever discourage action, and if we did, we’d be an extinct demographic. Constantly campaigning for help is a necessary, though often unpleasant, evil of activism. We must be inspiring leaders, seen as virtuous enough to earn support.

Society teaches that to be considered successful, an activist must act from selflessness, finding a perfect group of equally altruistic people to support their cause. How is this accomplished?

To even approach the impossible goal of humility, an activist’s team must admire their leader to the point of giving their cause effort for nothing in return: receiving compensation renders selflessness impossible, or at the very least doubtful. Therefore, a successful activist must motivate a team miraculously independent of money towards an unreachable goal of moral perfection. Fruitful activism must function off a single person’s ability to be so self-involved they believe in their own capability as a sole gleaming light of compassionate guidance.

This rotten core reveals the key problem in this grand scheme of change: successful activism must stem from humility, and achievement is rendered obsolete by narcissism. All rewards stem from conceit. Paradoxically, egomania has simultaneously become the only medium for success. Many would say that motive doesn't matter when it results in helping others regardless. To them, may I boldly suggest that, by some miracle of nature, we walk and chew gum at the same time? To be a successful activist is to be a liar, and therefore I “humbly” advise we become comfortable with instead being failures. Take Beatrice Alexander, a Jewish businesswoman of the early 20th century.

Alexander created the world’s first widely popular fashion doll brand. She crafted her first models after heroic figures such as WW1 front-line Red Cross nurses and later became one of the first to diversify her line by representing, in doll form, every member nation of the UN in native dress.

These efforts are far from benevolent. Alexander was hardly benefitless when it came to her work, with her dolls now selling for as much as twenty thousand dollars. Dolls are, unfortunately, not (yet) widely respected as a crucial definition of Americanism, and therefore Alexander will not be remembered as crucial to national identity. Alexander herself is consistently dismissed by historians as a businesswoman rather than humanitarian, ambitious rather than kind-hearted. By all standards set forth by modern activism she has been weighed and found wanting, declared by history a failed activist.

And yet, Alexander affected countless lives, contributing funds to Planned Parenthood, the Anti-Defamation League, and the Women’s League of Israel. She fought for gender equality, collected resources for disadvantaged youth in Israel, and helped provide immigrants with housing and employment. Must she be sorted into a simple box of either cold businesswoman or selfless benefactor? Can we not acknowledge both her undeniable personal business gain and depth as an activist?

The pursuit of humility should not be abandoned. We, as sentient, intelligent beings with countless capabilities, can hold both the goals of compassion and altruism in mind while fighting for change. Doubting the goals of changemakers such as Alexander is not just reasonable, but vital: criticism of individuals’ capitalizing on philanthropy is not retribution, it is a necessity for the improvement of activism.

We must, however, simultaneously acknowledge perfection as ultimately impossible. The key to positive change is learning to respect all forms of activism, especially mutually beneficial methods such as Alexander’s, as what they are: the best we can do.

We are all, at our cores, failures in advocacy. Maybe it is time to redefine what it means to be a success.

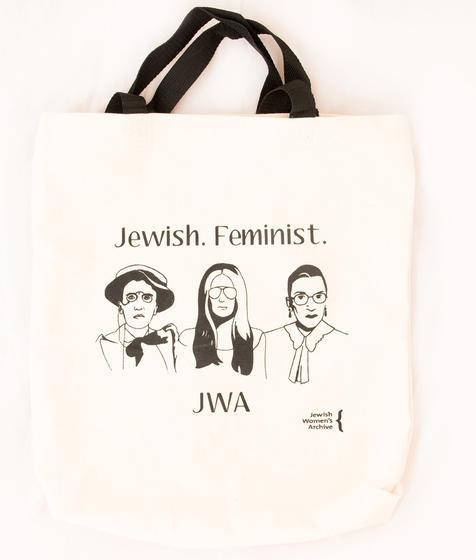

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.