Deciphering the Code

Dress codes. If you’ve been on the internet in the past few years, you’ve probably noticed that teenage girls tend to butt heads with them quite a bit. You may have read about how blatantly discriminatory dress codes are when it comes to gender. You might already be informed about how they contribute to victim blaming, are a form of slut shaming, and reinforce rape culture. Indeed, dress codes have become a sort-of gateway into feminist thought for teenage girls. For me, they were certainly a rude awakening.

Disclaimer: while dress codes are clearly sexist, I don’t think they’re exactly one of the biggest issues girls are facing at the moment. Conversations about dress codes are important, but the large amount of media coverage they’ve gotten has potentially derailed feminist discussion from more intersectional topics. And while dress codes aren't just for the privileged, the fact that being dress coded is one of the most tangible forms of oppression I've come into contact with says a lot about the types of privilege I do experience.

But for me, dress codes and my experiences with them served as more than just a frustration. They helped me come to an important realization that has certainly had an impact on my feminist identity: no matter how much privilege I have in other aspects of my identity, or how many “liberal” institutions and people I surround myself with, sexism is always going to be present in my life.

I had heard and read about how messed up dress codes were before I experienced them for myself. The archaic rules and sexist notions behind them that my friends and others had to deal with in their schools made me furious. However, I also felt extremely lucky that my own school did not enforce such policies, and considered myself safe from experiencing this type of sexism. So you can imagine how shocked I was when on an unbearably hot summer day at one of my favorite places in the world—my summer camp—I was asked to change my shirt. Why? Because it displayed a whopping one inch of my midriff.

I had always thought of camp as almost like a safe space—it was a place away from the rest of the world where I could express and explore my own identity without having to worry so much about being judged. I didn’t want to believe that my perfect little haven was in fact not immune from the sexism inherent in society at large. So I immediately questioned why I was being asked to change, hoping that my confusion would make the staff and administrators come to their progressive senses. I was met with the response that my stomach—and later on my upper thighs and the sides of my torso—were distracting, inappropriate, and potentially insulting. “This is a family-friendly camp,” they told me. “We just need to make sure that everyone is comfortable!” (With the obvious exception of malicious, no-good dress code violators such as myself.)

The more I questioned and was brought to upper levels of camp authority, the more I learned about our apparently quite detailed dress code, and the more dismayed I was by the undeniable sexism behind it. While my camp’s administration insisted that the dress code “treated boys and girls equally,” this was simply not true. Case in point: muscle tees. Boys were allowed to wear muscle tees, whereas girls were not. Girls couldn’t even wear muscle tees with a bandeau underneath, because bandeaus look like underwear, and underwear is (you guessed it) distracting. It was particularly frustrating to watch a friend get asked to change out of her muscle tee on the same day a boy our age was wearing a brightly tie-dyed and low-slung muscle tee with “420” emblazoned across his chest; needless to say, no one asked him to change.

But probably the most infuriating and illuminating aspect of my camp’s dress code was that I didn’t know about it until I broke it. After about a week of struggling, I was resigned to the fact that I probably wasn’t going to get the dress code changed. My new and less ambitious goal was to convince camp administrators to make our secret dress code more accessible, so that we would at least know what we were getting in trouble for.

But when I suggested that dress code information be included in the camp’s highly publicized packing list, the administrator I was speaking with insisted that this would be redundant and unnecessary. Her reasoning? The camp’s packing list requested “t-shirts” and “shorts,” which clearly didn’t include distinctively slutty articles of clothing like crop tops and spandex shorts, that were obviously inappropriate for camp. I was furious, not only at this misguided administrator who expected us to understand rules that were completely unclear, but also at the larger assumption behind that expectation. In expecting us to follow standards of dress that they never explicitly stated, the camp administrators assumed that girls should automatically understand the sexual implications of their bodies, and in turn should know to cover up without even being told to do so.

Needless to say, this experience shattered my perception of camp as a liberal safe haven of self-expression. But more importantly, it reshaped so much of what I had previously thought about sexism and feminism. There aren’t just sexist and non-sexist individuals and institutions; like other systems of oppression, sexism is a systemic, societal issue that exists in every setting. Sexism is so ingrained in society that it creates hundreds of gendered assumptions that we never even think to question, whether they be about the implications of our bodies, a person’s abilities, or even the kinds of behavior that we consider acceptable.

To this day, a really important part of the way I practice feminism is doing exactly what I did at camp: questioning. By questioning unjust norms and assumptions, wherever we may find them, we can begin to break down systems of oppression.

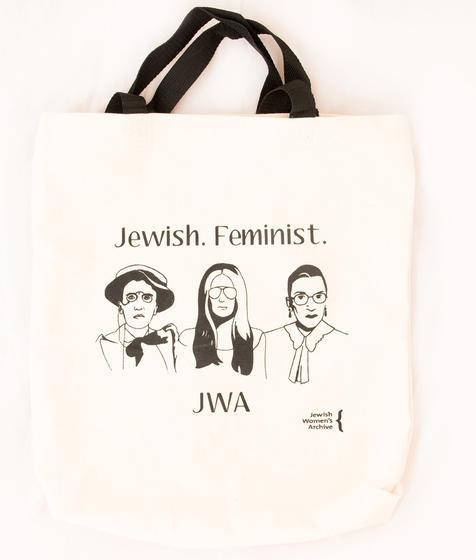

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.